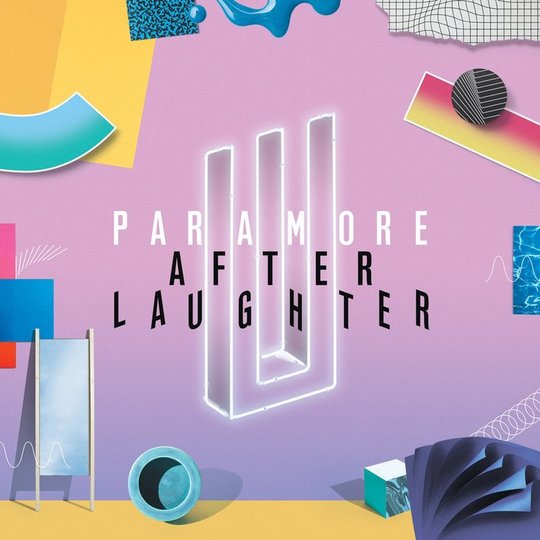

Most reviews of the new Paramore record that have run across this writer’s desk seem be under the misapprehension that the band have ‘gone pop’.

Where those critics have been for the past 12 years is mystifying. They’ve always been a pop band - they’ve played dress-up with varying degrees of honesty and success, sure, but they’ve always been a pop band, and that’s by no stretch of the imagination a criticism. Evidence is available in abundance as far back as their debut, 2005’s All We Know Is Falling, on which only the singles really provided any suggestion that they were ever destined to be more than just pop punk also-rans. For their part, though, ‘Pressure’ and ‘Emergency’ had hooks at their cores once you stripped away the brash chug of the guitars.

By the time Riot! followed in 2007, that gauche approach - of coating everything in a thick coat of noisy rock gloss - was failing to conceal the melodic heart beating beneath. ‘That’s What You Get’, a setlist staple to this day, is a wildly catchy singalong. ‘Misery Business’ and ‘crushcrushcrush’, meanwhile, both came complete with stomping choruses. Two years later, Brand New Eyes took them further in that direction whilst establishing them at arena level - the bratty ‘Ignorance’ was infectious, and you could hear the fists-in-the-air machinations whirring away beneath ‘Brick by Boring Brick’. Plus, it came complete with a bona fide acoustic ballad in ‘The Only Exception’.

It wasn’t until Paramore’s self-titled album arrived four years ago that the suggestion they’d crossed over into pop really began to gather pace - or perhaps that should be accusation, seeing as a small but vocal section of the fanbase met it with sufficient consternation to imply that they saw it as the band’s Dylan Goes Electric moment. It seemed a strange time for that particular penny to drop, given how sonically broad Paramore was; ‘Still Into You’ and ‘Ain’t It Fun’ were as commercially flirty as anything they’d ever written, but you could just as easily have attacked them for having ‘gone post-rock’ off the back of Explosions in the Sky take-off ‘Future’, or of chasing the country dollar with ‘Hate to See Your Heart Break’ (which, fittingly, they’d go on to re-record with Joy Williams of Americana flameouts The Civil Wars). At its core, though, it did feel like a pop record - just not in a manner dissimilar to their previous releases; sprawling and diverse, it’s an album that bears comparison to last year’s second effort by fellow stylistic magpies The 1975.

Still, fans were sure that something fundamental had changed, and they didn’t just mean the lineup, with guitarist Josh Farro and his drummer brother Zac having departed acrimoniously in 2010. Maybe it was their bitter letter of resignation that led to a bit of a lightbulb moment, including as it did allegations - later accepted as accurate - that singer Hayley Williams was the only member of the group signed to Atlantic Records, meaning that she is in effect a solo artist masquerading as a rock and roll frontwoman; there’s something inescapably chart-pop about that image. As it happened, that was something that Williams was getting a taste of around that time, supplying the chorus on forgotten rapper B.o.B’s ‘Airplanes’, which topped the singles rundown in Britain and peaked at two in the U.S.

The change that listeners were trying so hard to put their collective finger on was two-fold; Williams’ voice, and Williams’ demeanour. The shouty upstart approach that she took in the vocal booth for much of the first three albums fell by the wayside in favour of a multi-faceted style that conveyed a range of emotions and sold you on all of them; she was menacing on ‘Fast in My Car’, earnest on ‘Last Hope’, boisterous and carefree on ‘Anklebiters’. The latter Williams was the one we were starting to see in her writing, as well; suddenly, perhaps because of the extracurricular turbulence, she was devil-may-care, opening up more readily at the album’s more vulnerable points and sounding genuinely defiant whenever she struck a more upbeat tone. The line “if there’s a future we want it now”, from the LP’s first single, speaks volumes about her determination to drive the group forward, away from the car-wreck of the Farro fallout.

The concern was that we might not get that same Williams on the next record as and when it did surface. After all, from the outside looking in, she’s hardly been struggling in the interim, launching a successful hair dye company and, last February, marrying her sweetheart of nearly a decade. Plus, there was confirmation that she’d buried the hatchet with the Farros, first from Josh in an interview and then, more emphatically, from Zac when he rejoined the band last year in time for the LP5 sessions. Presumably, they’ve both moved past Williams’ deviation from her religious upbringing on Brand New Eyes, which was the other major reason cited for their exit - given that the most offensive lyric was apparently ‘Careful’s “the truth never set me free, so I did it myself”, we can safely assume that neither brother is an avid fan of Dimmu Borgir.

Our first taste of After Laughter, then, was a disarming one. Put the in-your-face new aesthetic aside for a second, as well as the niggling feeling you’ve heard this track on a Dutch Uncles record before, and you realise that the opening seconds of the music video for ‘Hard Times’ has a visibly uncertain Williams, eyes clouded with doubt, singing incisively about depression: “all that I want is to wake up fine”. Farro’s back behind the kit, but bassist Jeremy Davis is conspicuous by his absence; he moved on in late 2015, and a subsequent lawsuit over royalties as well as liberal use of the word ‘backstabbing’ in reference to Williams in interviews put to bed any possibility that it might have been a cordial divorce.

It seems logical that a major reason for Williams coming across as so much freer and more candid on Paramore was because the Farro affair had left a not inconsiderable dent in her butter-wouldn’t-melt public persona. Maybe the Davis situation left a similar cloud over her as she penned After Laughter, because thematically, this is an open sore of a record, one frequently scored through with a sense of profound sadness. ‘Fake Happy’ might be the most striking track lyrically, detailing as it does the struggle to put a brave face on mental health issues - think Rilo Kiley’s ‘A Better Son/Daughter’, updated for the Instagram generation. There’s also the excellent ‘Rose-Colored Boy’, on which a world-weary and worn-out Williams champions cynicism over wide-eyed optimism, whilst ‘Idle Worship’ (geddit) sees her seething as she addresses a topic that has to have been on her mind almost as long as she’s been in the band - the untenable pedestal that the fans have always placed her on.

The chorus on that track is brilliantly bouncy, like a lot of After Laughter. It’s a much more homogenous affair than Paramore was, curbing adventurous urges in favour of turning out something that sounds largely cohesive. You do wonder, though, if their reliance on an Eighties sound has been overstated; plenty of the songs are indebted to that decade’s penchant for having the synths at the front with the guitars used more for tone and colour, but the way some observers have gone on about it, you’d think the record was called FRANKIE SAY RELAX. Just as palpable is the influence of considerably more contemporary musicians; there’s more than a shade of CHVRCHES to the vocals on ‘Told You So’, which is of course unfortunate. Much more encouraging is ‘Forgiveness’, which sees Tegan and Sara’s last two LPs and raises them a glorious stab at Fleetwood Mac all of Williams’ own, apparently inspired in part by an awkward meeting with Josh Farro in a coffee shop shortly after he’d cut ties. Neither ‘Pool’ nor ‘Grudges’, meanwhile, would’ve been wildly out of place on the last Best Coast album, on which the standard was high.

Williams does, though, have a curious tendency to occasionally descend into treacly cutesiness without much warning; ‘Proof’ was the offending track on Paramore, and here, it’s ’26’, which does a good job of making She & Him sound like Sleaford Mods even before the fist-gnawingly unnecessary strings come in. ‘No Friend’ is the other misstep, on which Williams bizarrely steps aside to let Aaron Weiss of mewithoutYou ramble moodily; he’s apparently delivering a bruising commentary on Paramore’s career that casts them as being wracked with self-doubt, but his vocals are buried beneath a broiling sea of reverb and you can’t make out a word he’s saying. It’s a shame, because the track itself puts the polish and sheen aside in favour of something that sounds as bleak as many of Williams’ words, and it would’ve been interesting to see where she might’ve taken it herself.

Maybe it’s the following track, the album’s last, that does the best job of balancing sound and feeling; ‘Tell Me How’ is a tense treatise on relationship breakdowns and the awkward static that ensues - “of all the weapons you fight with / your silence is the most violent” being one of the record’s best lines. All the while, in the background, are those arpeggiated, chirpy guitars that characterise so much of the album’s poppiness, but this time, they’re playing quietly. It’s hard to imagine that a Paramore crowd might be the kind to shout “Judas!” at the stage but, even if they were, such heckling would be misguided. After Laughter isn’t a reinvention. It’s the sound of Paramore casting off the weight of other people’s expectations. Williams has managed to get out from under the pressure of having to be the perma-grinning frontwoman, and the emotional uncertainty that’s exposed is fascinating. Musically, meanwhile, this is as free as they’ve ever sounded. Again: Paramore have always been a pop band. They’ve just never been this proud of it.

-

8Joe Goggins's Score