Using a combination of lies, subterfuge, occasional guestlist and frequently our own money, DiS has spent the last week fluttering about London excitedly soaking up the once in a lifetime thrills of Ornette Coleman's Meltdown festival at the Southbank Centre. We still don't really know what harmolodics are, but we do know what our highlights were - they're the things we've written about down there.

The Roots

Just before the encore, MC Black Thought distills the feeling inside the venue: “This is once in a lifetime stuff. You’re never going to experience anything like this again.” True to his word; The Roots are peerless, lean virtuosos who seem to define musical audacity. ?uestlove and his crew make a mockery of the notion that hip-hop has to suffer when a live band takes the place of samples. They enter the stage and proceed to lay down several hip hop classics, not of their own making, but still sounding every bit as good as the originals by Rakim, Run DMC and the Wu Tang Clan. When they turn their attentions back to their own catalogue, every song is optimised for live performance. ?uestlove’s magnificent drumming keeps the focus razor sharp, even when five minute songs are extended past the twenty minute mark. The Roots are renegades from the era of hip hop before it was tainted by bling and crunk. They are a tight jazz band who happens to have one of the most skilled MCs in the game in front of them. They are the kids who grew up listening to soul but now feel equally happy referencing Radiohead and Fela Kuti. It takes a special kind of act to open a festival curated by a genuine living legend, but they nail it. Nights this special do only happen once in a lifetime. (Bob Ferguson)

Yoko Ono And The Plastic Ono Band

“Yeah... I’m not entirely certain what Yoko Ono’s place in music really is” muses an acquaintance with a usually encyclopaedic grasp of the avant garde, a couple of days after the first UK performance from the Plastic Ono Band in four decades. No shit. While we’re all hopefully smart enough to get beyond that nonsense about her being responsible for The Beatles’ demise, the sprawling explorations of Ono’s lengthy musical career don’t tend to get credited with a cultural impact on a par with her celebrity – woman cannot live on namechecks by Sonic Youth alone. Tonight’s show in some respect offers vindication: the Plastic Ono Band – Ringo out, Sean Lennon/Cornelius/Anthony Hegarty/surprisingly un-annoying Mark Ronson/about ten others in - are awesome, thunderous psyche grooves spitting feedback, building, building, building to those all important climaxes – the lady had a hand in post rock, let’s say that. Ono herself is a small, absurdly spry old dear who runs around scatting a bit and occasionally singing badly: not to do her down at all, but in the context of the show she’s more like a hype woman, and at times feels rather superfluous next to a breathtakingly well-drilled band that shares not a member with the original incarnation of the POB. Nonetheless, it’s the music she created, and it sounds pretty amazing, hurtling towards a climactic, electronic blitz through ‘Mind Train’, a frail but dignified Coleman on hand to scorch its tracks with shrill fire. (Andrzej Lukowski)

The Freewheeling Yo La Tengo

“Have you ever been to Antartica?!” Insofar as heckles go, I’d put it right up there with the very best. The only caveat is that Yo La Tengo have, for one night only, legitimised heckling. The ‘Freewheeling’ prefix denotes the unique Q & A format – the audience yells something inaudible, Ira Kaplan shouts out a comedy response, they play a song loosely related to his answer. Though there's the suspicion it could be a long night, Ira, Georgia and James are funny in all the right ways, it turns out. They’re smart enough to handle the nerds, and relaxed enough to be off-the-cuff witty. That the stripped down quasi-acoustic setup doesn’t have to mean downtempo is debunked three songs in by a shattering version of garage staple 'Come On Up' as recently covered by Condo Fucks. It’s as startling to hear the clear set highlight being played at all as it is to see it being played seated on an electrified acoustic guitar. And that’s not the only rare delight on offer tonight: a heartmelting cover of the Velvet Underground’s 'I Found a Reason' and a Bob Dylan cover that turns out to have been '4th Time Round' star alongside a version of 'Drug Test' stripped down to the point of hauntedness. And whilst DiS might lament the lack of the band’s freakier, krautier songs, it’s hard to fault a set that opens with an airy, Georgia-led 'Tom Courtenay' and still finds room to include a tear-inducing 'Nowhere Near'. The band do come unstuck at times: when one vocal punter mentions that he likes to do the dirty to 'Little Eyes', YLT are almost as dumbstruck as one expects his poor wife will be when she finds out he told an entire concert hall about their song. Similarly, the format's double-edged nature becomes clear by the end when a previously 'reticent' crowd are pelting the stage with questions which Ira amiably ducks and dodges. Yet as the band encore with a second, beefier, Ira-led run through as 'Tom Courtenay”' that feels, if anything, a bit more necessary than the first one, there’s a warm feeling that just can’t be shook. (Philip Bloomfield)

Patti Smith & A Silver Mount Zion

Video: Patti Smith & A Silver Mount Zion: 'Ghost Dance'

Curator of her own Meltdown in 2005, Patti Smith is on fine communicative form for Ornette Coleman's, making clear her performance will be in keeping with the avant-garde jazzman’s modus operandi by avoiding repetition. Instead, she quests to reinterpret old songs and poems. She even plays one song, ‘Nine’, that’s barely a week old. In fact, it’s so new that she has to check with Efrim Menuck from A Silver Mt Zion - who accompany for the latter half - which key they’ve decided to play it in. (D, if you’re interested.) Following a compelling support performance from Austrian wunderkind Soap&Skin, Smith begins with a solo recital of her scabrous, autobiographical beat poem ‘Piss Factory’, which serves to remind that although she came to prominence in the punk era, she’s really a product of the idealistic musical and literary schools of the late-Fifties and early-Sixties. Prior to SMZ taking the stage Smith is joined for another poem by her daughter on piano, Portishead’s Adrian Utley, and frequent collaborator Flea, who performs some staggering sampler-augmented bass-work and frugs like he’s stepping on a livewire even during quieter moments. One of several highlights occurs when he and Smith are joined by the green-robed Master Musicians of Jajouka: the spiralling relentlessness of their flute and drum assault is transporting, especially when Smith, crying out about Pan above the tumult, throws down some squalling clarinet blasts of her own. The final part of the set witnesses A Silver Mt. Zion (with Flea on bass; that’s A Silver Mt. Zion with Flea. Just want to make sure you’ve got that) flesh out the sound, cello, violin and guitars building up into atonal climaxes above which Smith. Her reconfigured ‘People Have the Power’ takes in the Iranian election, while the encore of ‘Pissing in a River’ and ‘Ghost Dance’ is the capstone on a concert that just might, as Ornette Coleman puts it in a brief onstage appearance “be remembered forever.” (Chris Power)

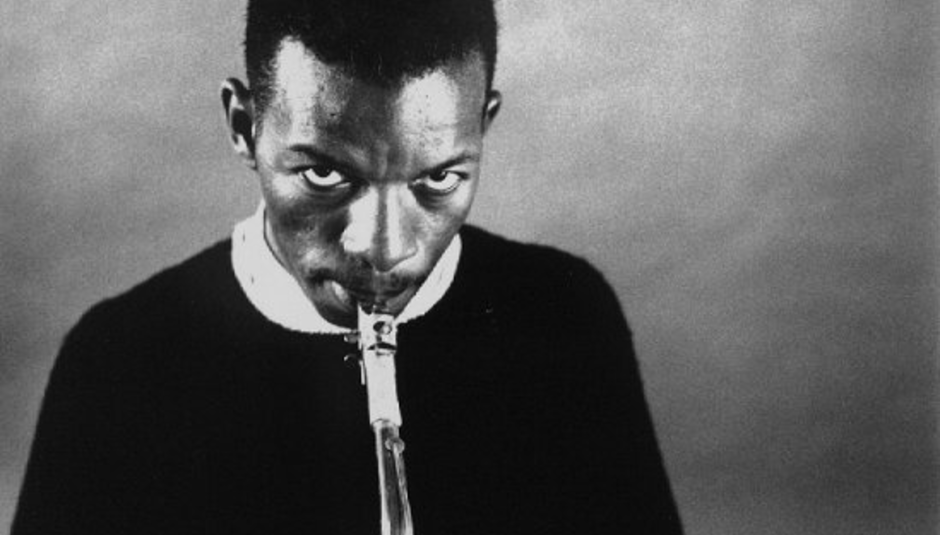

Ornette Coleman: Reflections On This Is Our Music

In 1991, Miles Davis - jazz’s greatest innovator - returned to pieces from his Forties and Fifties repertoire for the first time in decades. The collaboration with Quincy Jones, documented on the Miles & Quincy Live In Montreux LP, is generally cited as the only moment of nostalgia of the great man’s professional life: months later he was dead. Whilst we certainly hope it’s not his final act, at the grand old age of 78, curating the Meltdown Festival is very likely the last large scale project of Ornette Coleman’s equally heady career. Coleman, like Davis, could be forgiven adopting a certain degree of sentimentality as he gathered together admirers, fellow travellers and co-conspirators in the hazy world of harmolodics – his own ill-defined musical theory – for the festival’s final night.

The last concert of Meltdown, subtitled Reflections on This Is Our Music, was ostensibly a meditation on that milestone 1960 record. Alongside the previous year’s The Shape Of Jazz To Come (which was similarly celebrated two night’s previously) and the follow-up, Free Jazz, This Is Our Music both defines the saxophonist’s music and remains amongst its most-prized examples. In truth, as is so often the case, the practice didn’t quite follow the theory. It wasn’t until halfway through the evening that the record’s startling opening refrain was heard, and even then the fractious blast that begins ‘Blues Connotation’ wasn’t played by Coleman. Originally a joint solo that saw Ornette’s patent white plastic sax tear away from the trumpet of Don Cherry, this time it came storming out of the three bass attack of Tony Falanga, Al MacDowell and enthusiastic guest star Flea. Whether this was due to Coleman’s fading strength is up for debate, but the version of ‘Blues Connotation’ presented was nonetheless a highlight of a sometimes patchy, sometimes spectacular set. Coleman’s own interventions here were intricately timed: while he occasionally lacks the visceral power he once had, his soloing has retained the intelligence and originality that made him such a star.

What had come before was less successful. Tony Falanga’s bowed double bass take on the prelude to Bach’s G Major Cello Suite had proved an unexpected thrill, as Coleman and cohorts hacked into its elegant structure with howls and thuds, slowly ripping apart Bach’s original. But there were a couple of stop-start intros going wrong that were reminiscent of Spy vs Spy, John Zorn’s notorious high-speed takes on Coleman’s music from 1988, and a bizarre appearance by Baaba Maal, whose sonorous vocals failed to mesh with Coleman’s music, and an embarrassing moment where Ornette got the audience to clap along (fortunately it didn’t take them long to realise they couldn’t keep Ornette’s time). Coleman was also quick to pick up his violin and trumpet (he is neither a violinist or a trumpeter), proving his commitment to investigations into timbre and tone as much as melody and harmony, but too often his own sound was lost in the mess.

The blame must be at least partially down to Coleman’s drummer and son, Denardo. An idiosyncratic, utterly unsubtle and seemingly untutored presence, he has been appearing on his father’s records since 1966, when he was ten, and plays a key role in managing both Ornette and hisband. It is significant that when they are joined onstage by Bachir Attar and the Master Musicians Of Jajouka, Flea looks to Coleman Junior, rather than Coleman Senior, for direction. Denardo Coleman can add the kind of thunder to the band that was, at the time of This Is Our Music, the signature of Ed Blackwell, but this can be distracting – and the fact it’s an almost non-stop assault doesn’t leave much room for dynamic shifts. When he’s working with a big sound though, it really does work, and it is the arrival of the eight Master Musicians Of Jajouka that heralds the show’s preeminent point. During their support slot, their hypnotic Sufi trance rhythms and looping reed refrains had seemed almost mind-numbingly repetitious, but as a foil to Coleman and his band they appeared heroic. Their music provided the kind of solid backbone that Denardo and the trio of bassists had never attempted, allowing the whole band to play to their individual strengths, improvising thrillingly on top.

After a standing ovation Coleman returned for one of the most clearly pre-planned encores imaginable. The final billed guest star, whose instrument had lain at the back of the stage all evening, was Charlie Haden, Coleman’s original bassist, and indeed the first of his fellow musicians to recognise his brilliance and ask to play with him. The pair played a single standout song in a trio with Denardo Coleman. Ironically the song was ‘Lonely Woman’, the classic track from The Shape Of Jazz To Come, which apparently didn't get an airing at the concert that bore that album’s name. It was a stunning finale, not merely a nostalgic salute to long-gone era, but a great moment musically. Coleman returned to the stage once more to shake hands with fans and sign autographs until the soundman had to drag him away. After two of the most intensive weeks of his life, he thoroughly deserved to revel in the praise. (Mark Ward)