Covering subjects such as stabbing people with biros, anally raping corpses, and having sex with 14-year-olds, behind all the unsavoury imagery on Plan B’s 2006 debut album was an outraged moralist, appalled at the inequality and injustice of the world he saw around him, like some kind of be-hoodied Bret Easton Ellis.

This was not hugely commercial subject matter and for 2010’s The Defamation of Strickland Banks the scruffy rapper reinvented himself as a suit-sporting, smooth-crooning pop singer. The transformation was remarkable. While cynical and embarrassing, it was so unprecedented, so drastic and such a success that it was difficult not to begrudgingly admire. With a dubious concept centred around a rape allegation that lands its protagonist in jail, the record’s slick soul sounded less like Plan B (aka Ben Drew) had been incarcerated in Strangeways than in Brit School.

Returning his intense, disgruntled rapping to the fore, Ill Manors witnesses the resurrection of angry B. And yes, the riots-referencing title track is the greatest British protest song in years (even if its only noticeable competition is the anti-capitalist anthem ‘Price Tag’ by jumpsuit-flaunting Marxist polemicist Jessie J).

After this confrontational opening ditty, Ill Manors becomes less overtly political but no less vivid, as the remaining tracks depict in gruesome detail the dismal lives of London’s underclass. The polished beats are complemented by dark RZA-influenced effects and the angsty verses interrupted with catchy blues choruses, appearances from the likes of Labrinth and John Cooper Clarke, and samples from Drew’s accompanying feature film. I’ve not seen the movie, but it was so powerful it convinced Edwina Currie (of all people) that Drew is a 'twenty-first century Dickens'.

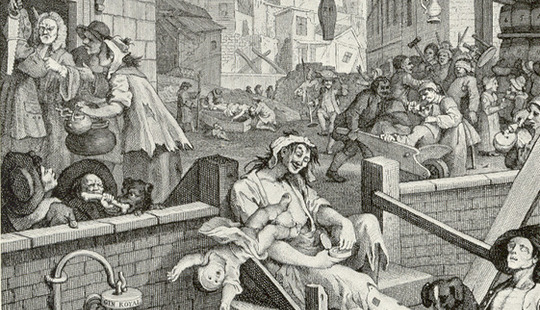

These songs, however, suggest that we look beyond the long-winded, over-sentimental output of Dickens to an earlier archetype. To an artist living in a less polite age and working in a more immediately striking form. To an eighteenth-century painter whose father (like that of the Victorian writer’s) had also been incarcerated in a debtors’ prison and whose eye for the urban landscape and the lives of its people inspired Dickens. To William Hogarth.

Gin Lane now flows with crack rather than cheap booze and snuff. Whereas Hogarth’s Moll Hackabout travelled from the English countryside to London to be exploited in the bawdy-house, Drew’s Katya character is sex-trafficked from Eastern Europe, escaping her pimp only to return to prostitution when unable to find employment. B’s harlots progress through similarly bleak lives of suffering and exploitation, while their innocent and unfortunate children are shamefully neglected. Hogarth’s babies were deserted or dropped down stairwells by their drunken or prostitute mothers; Drew’s are attacked by racists in basements while their addict mums have sex for cash upstairs. Each artist expresses sympathy for those whose lives have been ruined by poverty, coupled with a frustration towards the sometimes hopelessly nihilistic attitudes of the poor. And occasionally the social outrage veers into bleakly absurd caricature, such as when Katya is described “getting fucked in the field from behind while you breastfeed your child just so it don’t cry”.

Yes, Plan B mocks the Right’s ‘Broken Britain’ rhetoric while portraying a country which if not exactly broken appears divided and depressing. Yes, he rages against the injustices of capitalism and strives to deliver an alternative to the unadulterated materialism of hip-hop while advertising laptop sound systems and cider variants. Yes, he bemoans the problems of society and berates those who contribute to its sorry state without providing much of a solution.

Yet his music is heartfelt, his concerns have reached a wide audience, inciting debate, and satire’s purpose is not to provide solutions - and this record is satire, if a rather despairing form which is unlikely to inspire much laughter. Satire can explore, provoke, unsettle, it can encourage examination and contemplation, but it tends to shy away from supplying answers or conclusions and the satirist’s principal motivation is to advance his or her career by producing good work.

With rich boy politicians unlikely to change their attitudes or approaches anytime soon, this album (and, I gather, the film) implies that if there is a way to escape the bleak world of Ill Manors, it lies with the determination of the individual to make the right moral choices, avoid the temptations of crime and vice, and work damn hard to get out. In a world where the only religion is greedy materialism (‘Lost My Way’), it seems the one thing that can save us is the good old-fashioned Protestant work ethic - just like the one promoted in Industry and Idleness (1747).

Behold Ben Drew, the modern Hogarth.

-

8J.R. Moores's Score