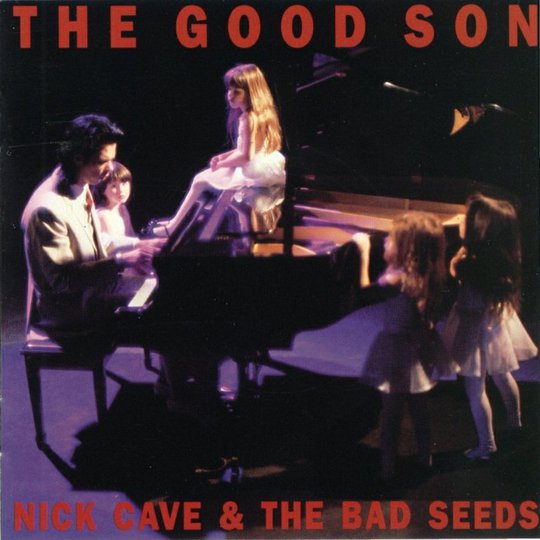

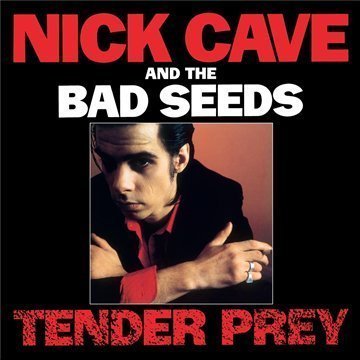

What the Blixa is Nick Cave playing at? It’s easy to imagine that being the reaction of many Cave devotees in the spring of 1990, when The Good Son and its first single, ‘The Ship Song’, were released. Cave and the Bad Seeds’ previous album, 1988’s Tender Prey, was a clanky, cranky masterpiece: alternately thunderous and haunted, it sounded as sordid and despairing as its balefully staring cover star looked. A rehab stint and several months spent vegetating in a London flat later, however, and the cleaned-up Nick is pictured at the piano in a white tuxedo, surrounded by angelic little girls, none of whom appear to be sobbing or asking if the creepy stick-man will go away…

‘The Ship Song’ itself marks the first appearance of what we now recognise as the ‘mature’ Cave, who emerged more fully in the wake of The Boatman’s Call. Lauded by the broadsheets; a staple of Later…with Jools Holland; spurning Old Testament blood and retribution for New Testament love and forgiveness: it’s a dignified situation for an elder statesman of post-punk, and one which only recently has he tried to undermine with Grinderman. Although Cave had always had time for ballads, out-wallowing Elvis on The Bad Seeds’ debut single, ‘In The Ghetto’, ‘The Ship Song’, with its uplifting, major-key chorus, spoken declarations of devotion and a wholly unironic glockenspiel solo from Mick Harvey, took a further step towards unabashed sentiment.

Not everything is quite as it seems, of course, and just as the single’s video reveals Nick’s spotless turn to be a pastiche of a now-passed era of entertainer – the appearance of Harvey, Kid Congo Powers and a bottle-brush-haired Blixa Bargeld as a trio of crooning backing singers knowingly winks at the band’s new, scrubbed-clean image – so ‘The Ship Song’ has become one of those poisoned love standards, drawing dewy-eyed couples closer before planting a chill into their hearts with the lines, “Your face has fallen sad now / For you know the time is nigh / When I must remove your wings / And you, you must try to fly”.

And equally, The Good Son is much, much more than Cave going soft. As a transitional album, there’s plenty here for fans of both Cave the lover and Cave the fighter. And Cave the storyteller: still gloriously wild-eyed, yet with the grotesque excesses of yore replaced by a more humane perspective.

In contrast to Tender Prey’s neutron-star heavy opener, ‘The Mercy Seat’, The Good Son sets out its stall with ‘Foi Na Cruz’, a gentle marriage of bittersweet love verse and an old Portuguese hymn. But even this apparently mild-mannered paean to a new start in Brazil (where the album was recorded) feels restless and claustrophobic. Weighed down by a whirl of strings, its chorus of Brazilian singers repeat endless pieties in search of salvation. The album’s title track brings simmering conflict to full boil. A retelling of the parable of the prodigal son from the point of the view of the brother who stayed behind, it sees his resentment building under the pressure of great thundering granite slabs of guitar. Yet as the ‘good’ son rails at life’s unfairness and “curses his virtue like an unclean thing”, the fury dissipates to grief, escaping skywards with a Morricone-esque wash of strings that suggests God shrugging his shoulders. The same occurs on ‘Sorrow’s Child’ where a lachrymose piano ballad swirls helplessly, never finding the hoped-for resolution.

After that trio of downers, it’s a relief to reach ‘The Weeping Song’. Here, exchanges between Cave and the sepulchral-toned Bargeld find salvation in the darkest of comedy: “Father, why are all the children weeping? / They are merely crying, son / O are they merely crying, father? / Yes, true weeping is yet to come”. Featured on this reissue’s second disc, the video is equally tongue-in-cheek, with Cave and Bargeld swigging retsina in a rowing boat tossed on a bin-bag sea. Along with the aforementioned video for ‘The Ship Song’, the extras also include a clutch of B-sides, of which the best is the bruised, masochistic ‘The Train Song’, and an instalment of Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard’s film, Do You Love Me Like I Love You, where band members, Bad Seeds associates and random fans riff upon the album’s making and meanings.

‘The Hammer Song’ sees another son cast adrift, tormented by visions and an unbearable guilt, with Mick Harvey’s vibraphone punctuating more stormily cinematic arrangements. ‘Lament’ mopes over the latest of Cave’s mysterious beauties, whose “fairground hair” and “seaside eyes” portend the inevitable farewell. But he’s soon chivvied back to his leering, vengeful best with ‘The Witness Song’, a gospel knees-up where false hope is scornfully decried from a Hammond-stacked pulpit as the Bad Seeds gleefully lay waste to all around them.

True redemption comes at last, however, in the form of the closing ballad ‘Lucy’, whose shimmering piano coda sees the previous songs’ burden melt away into tentative hope. It’s not easy being good, but on this album at least, Cave and the Bad Seeds make it sound almost as alluring as being bad.

-

9Abi Bliss's Score