‘Look, let’s not beat around the bush here: this is shit. I know it’s shit, you know it’s shit. I’ve reviewed some shit albums in the past and I’ve said some pretty mean, albeit justified, things about Beady Eye and The Strypes. [NAME OF BAND REDACTED] are very much as shit as those bands, but this time, what’s the use in summoning the energy to come up with a crushing metaphor?’

It was never boring proofing Dan’s copy, and the above is an excerpt from a review that he wrote that got pulled because Sean not unreasonably thought it had crossed a line of appropriateness with regards to a band that probably did, on reflection, deserve a modicum of respect.

I’m not sure how many times Dan informed me he was quitting DiS – either because he was swamped with actual proper work, or because he’d managed to bring down a social media hate mob down on himself (again) and was a bit freaked out. One of the last ever emails he sent me was a cc’d request to remove him from the contributors’ list. I didn’t reply, or indeed remove him, partly because I was doubtful as to whether he entirely meant it, partly because I just hoped that if I left him on he’d just start doing stuff again anyway.

Much of Dan’s curmudgeonly reputation was founded on two reviews: Cast’s Troubled Times, and, of course, Beady Eye’s BE. If he’d had his way there would definitely have been a few more, but I (to a lesser extent) and Sean (to a greater extent) felt ambivalence about that sort of writing, even if Dan did it magnificently well, and I had a tendency to avoid assigning him punchbag-style reviews afterwards. It would be patently untrue to suggest that his sports journalism career took off because we stopped him from getting embroiled in quite as many spats with ladrock bands as he’d ideally like, but there is part of me that imagines it didn’t hurt.

Still, Dan remained probably our only writer who I actively braced myself before reading, with the questions ‘Is this libellous?’ ‘Will it make Sean freak out?’ and ‘Is the artist in question strong enough emotionally to cope with this?’ always at the back of my mind. This was a good thing.

However really, for me, he was less defined by outrageous provocation, more the way – like every truly great writer – he would cheerily go wildly off-piste in order to make his music reviews lavish, hilarious catalogues of his other interests. If you really want to pay tribute to him, browse his body of work – be it DiS, The Guardian, The Telegraph or Under the Radar – and drink a finger every time he mentions football, cricket, the films of Woody Allen and, of course, his beloved The Simpsons. (You’ll be paralytic after about five articles).

So a quintessential Dan Lucas article is his review of The Duckworth Lewis Method’s Sticky Wickets. They were a cricket themed band co-fronted by Neil Hannon, of The Divine Comedy fame and were basically precision engineered to delight Dan. Far from a grump, the sheer energetic gusto of his review was a genuine delight: he was so happy to actually be given licence to write about cricket in a music article that his writing ebulliently zoomed further and further away from the record in question, deeper and deeper into a tongue-in-cheek digression on the difference between test cricket and Twenty20, before he cheerily remembered he should say something about the music, which he does for about a paragraph at the end. He initially gave it 10/10 – I told him that was absurd, based on what he had written, and asked whether it was possible he was, in fact, trying to give cricket 10/10, which he conceded may have been the case and lopped a couple of marks off.

Anyway: if he’d been born ten or 20 years earlier, Dan would have been the sort of unchecked contrarian juggernaut that powered the British music press’s golden age. That sort of thing doesn’t happen anymore, but that was fine, as he was good enough to write about cricket, football, rugby and I believe on one occasion ice hockey for two diametrically politically opposed broadsheets.

Because my social life has been torpedoed by the twin demons of having a family and a job that requires me to be at the theatre most nights (Dan loathed the theatre, or cheerily maintained he did) I never hung out with Dan a lot in person, but we were friends as well as colleagues, I hope. The last message he sent to me directly was on Feb 18, via Facebook, to tell me that the actor Warren Frost had died. I started typing a response so garbled I didn’t send it, basically saying I’d been shocked but then realised that the guy we both knew as the sixtysomething Doctor Hayward in Twin Peaks had in fact reached the respectable age of 91. It was a weird last communication to have and it’s pure narcissism to read too much into it, but it is bitterly sad and brutally unfair that Dan didn’t get to enjoy the long, full life that was owed to him.

Andrzej Lukowski

I’m sure I said this in another review recently, but the best albums are great in context. Straight Outta Compton for example probably wouldn’t be considered so important without the background of racial tension from which it was born; Rumours is perfect because of the tensions and tortured breakups within the band during recording rather than in spite of them. For clarity’s sake, I’ll take this moment to assure readers that I’m absolutely NOT saying that Sticky Wickets is in the same league as Straight Outta Compton or Rumours. But in its own field (pitch?) it's as much a triumph of either.

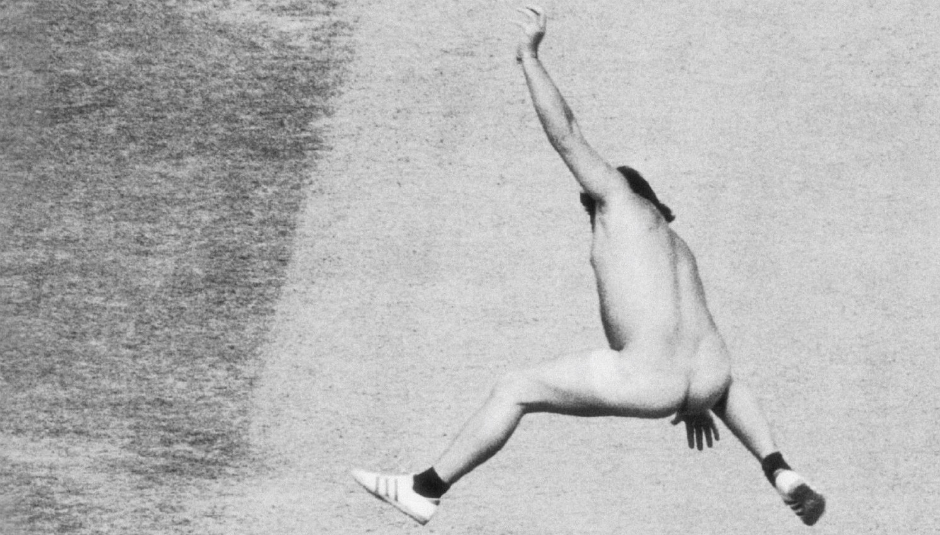

So Sticky Wickets, the second innings from The Duckworth Lewis Method, is to be judged within the genre of concept albums about cricket. Weak jokes aside, there is an argument to be made for cricket as the sport of rock and roll. Nothing else has the drama of a test match: the shift in momentum that can be allowed to play out almost imperceptibly over a day or the one dramatic over that can alter the entire complexion of a match. Yes, a five-day match can seem dull when compared to the instant gratification of other sports or even T20 cricket, but the dedication required and the ultimate reward and enjoyment are the same as that which can be found in a seminal Krautrock album or a great jazz composition. The joy of watching the most resilient batsman fending off a hostile spell on a green wicket or a wristy spinner in a subcontinental dustbowl can really only be achieved through the same all-consuming persistence as that needed to fully appreciate, say, some of the more left-field indie records of the past twenty years. Moreover, no other sport could ever inspire The Divine Comedy’s Neil Hannon and Pugwash’s Thomas Walsh to write two full concept albums about it.

The great commentator John Arlott famously described Clive Lloyd pulling the ball into the Mound Stand at Lord’s in 1975 as “The stroke of a man knocking a thistle top off with a walking stick”, however the more mortals among us can rarely hope for such evocative eloquence in the days of Twitter and the hashtag. Instead the world of music can offer the most apposite metaphors for a pastime so poetic: I have previously argued the merits of Gordon Greenidge over Virender Sehwag at the top of an all-time XI’s order by describing the merits of Clapton’s druggy, dripping Cream-era guitar riffs over the immediate bombast of a Metallica album. Meanwhile, I confess to having had one of those nerdy discussions over a ‘Reckoner’ XI : a collated team of players whose artistic style echoes the organic fluidity of the gorgeous Radiohead track.

Then you have 10CC’s oft-misinterpreted ‘Dreadlock Holiday’, Rory Bremner’s ‘N-n-n-n Nineteen Not Out’ ('An unlistenable crime against music… a cricketing parody of Paul Hardcastle’s scarcely-less-terrible "Nineteen"' according to The Guardian’s Andy Bull) and Roy Harper’s lovely ‘When an Old Cricketer Leaves the Crease’, so beloved by John Peel that it was played on air after his death at his request. It’s worth mentioning too, some of the personal anecdotes that musicians like to recall about the game: from the somewhat inauspicious (Harry Judd from McFly, Johnny Borrell of Razorlight, David Essex) to the iconic (George Harrison, Clapton, Elton John, Rolling Stones Charlie Watts and Mick Jagger), BBC Radio 4’s Test Match Special has heard some fascinating first-hand stories over recent years. Former England bowler Mike Selvey once recalled to me the time that Clapton and Harrison played in a pub in Worcester after going down to see Botham play, and the time he and his teammates were visited in the Lord’s dressing room by a young Elton John. He also talked about The Stranglers’ Hugh Cornwell, who in 1990 was watching a Test between India and England and saw England fast bowler and hapless batsman Devon Malcolm break free from the shackles of being tied down by India’s bowlers with an agricultural heave into the stands for six; he would later cite this moment of release as his inspiration for leaving The Stranglers and embarking on the next stage of his career, going it alone outside of the familiar confines of the band.

I have no evidence, anecdotal or otherwise, to confirm this, but I also recall reading that ELO’s Jeff Lynne is something of a cricket tragic. This neatly brings us full circle, for Sticky Wickets sees the duo further indulge in their love of Birmingham’s greatest ever band (and I say this as someone who was brought up by Ocean Colour Scene loving parents). The Light Orchestral influences were heavily evident on their eponymous début but had anyone told you this was a bonus disc of outtakes from Out of the Blue then only the lyrics would betray them. A rocking, anachronistic Seventies pop rock riff leads the way on opener ‘Sticky Wickets’ as Walsh proffers advice for openers batting on era-appropriate uncovered pitches – “Don’t get caught trying to hit the big shot... it’s no good playing on the back foot.” Elsewhere there are almost direct ELO correlations. ‘Third Man’ sounds like ‘Telephone Line’ from melody through to brilliant vocoder breakdown; ‘It’s Just Not Cricket’ is the album’s ‘Diary of Horace Wimp’. It’s a sound so perfect that the duo only really veer away from it once, as ‘Line and Length’ sounds closer to LCD Soundsystem’s ‘Us and Them’.

Sticky Wickets is certainly more Village Green Preservation Society than Fire in Babylon in tone. The only point where Twenty20-esque glamour is touched upon is ‘Boom Boom Afridi’, with David 'Bumble' Lloyd helping out on vocal duties in tribute to the hard-hitting Pakistani all-rounder. For the rest of the album though it’s outdated playing conditions on the title track, the sad existential musings of ‘The Umpire’ (“We’re only here to be sneered at, just a relic of yesteryear/There was a time when we were held high, but it’s not how it used to be/They only let us stick around so they’ve someone to kick around”) or the hapless fielder being put out to pasture at third man on, er, ‘Third Man’ (featuring a reading from Harry Potter Daniel Radcliffe). There’s Python-esque joviality on ‘The Laughing Cavaliers’, which features Hannon’s local Taverners team, but it’s really a reminder of the sort of level the Cricket Tragic can aspire to, rather than thinking Viv Richards is just like us.

'Cricket Tragic' is the key here. Cricket and rock music have a long history, and at points, it all gets a bit glamorous. Sticky Wickets isn’t concerned with those, though: it takes the things that makes the loner, the geek, the loser, the tragic feel all warm and fuzzy, and then makes that sound like ELO. And nothing this year has made me feel happier than that. FoW.