“You’re spit into the centre of your hometown,” goes the opening line of the song. “There are leaves on the street, and there are friends around you now.”

Nested within the larger town of Plainfield in New Hampshire, Meriden is home to private boarding school Kimball Union Academy and a population of around 500. It is where Okkervil River bandleader Will Sheff was raised (his parents both taught at the school), and the subject of his band’s seventh album, The Silver Gymnasium, in which he considers his childhood and what it’s like to grow up in a close-knit, rural community. (The quoted song is ‘Down Down The Deep River’.)

I call Will from my hometown in Devon at the beginning of August, where I’ve arrived a couple of nights previously for my summer holiday. The day before the interview, I burn my downloaded promo of the album onto a CD-R and drive around listening to it while calling on friends. When I reach Will, he’s padding around a dormitory in his hometown, where he’s working on “a million projects” during the run-up to the album’s release. “It’s really awesome to be back,” he tells me, and when I tell him that I’m back in my hometown too, and how I’ve been listening to the album in the car, he’s delighted: “That’s how it was intended to be listened to: driving.”

Produced by studio veteran John Agnello (who Will sought out specifically due to his involvement in some of the defining LPs of the 1980s), it is a record of relentless forward motion: of memories both foggy and sharp; of warmth, colour and affection offset by traces of darkness. It is different to 2011’s wild and blustery I Am Very Far - a set of songs its architect considers “by design unapproachable” - in almost every conceivable way. He elucidates: “The idea was that there’s something in there but we can’t get to it, like trying to grapple up castle walls and peer through a hole in the stone. It seemed like the thing to do after that was something friendly, and fun. And fun-loving. Let the wall completely fall down.”

That, and that after a rough year, he considers himself to be in a “no bullshit” kind of place. I tell him that I related to The Silver Gymnasium immediately (which wasn’t the case with I Am Very Far), and he’s pleased. This is the third time I’ve spoken to him, and despite each interview being a couple of years apart, I quickly remember what it’s like. He is fond of metaphor - spinning one after the other - but none of them sound rehearsed and they all make sense. He loves to talk, and makes for fascinating conversation: opinionated and frank, formidably intelligent and full of theories and ideas he’s happy to expound on. This is good, as I don’t have much of an outline for the interview. Later I’ll just throw words and references from the album out there and see what has to say about them, like ‘starship’ (“that’s a great word for a spaceship”) and ‘Pitfall’ (“After one look at it, you were like, ‘Get out of the way, give me the controller, I gotta play this’”).

It’s also good because he’s just a pleasure to speak to.

The Silver Gymnasium is an album he feels he was “always training for,” and indeed, the band have touched on its themes before; explicitly so in the old home movies that made up the video for I Am Very Far’s ‘Your Past Life As A Blast’. In high school, a (perhaps over-zealous) English teacher turned Will on to Dylan Thomas’s Under Milk Wood, and in turn Joyce’s Ulysses, Faulkner and Proust. “I didn’t really understand all of them,” he says of his early reading, “But it had a profound impact on me. There’s always [in those stories] this sense of things being rooted in the local. I always knew that there were a million - well, maybe 500 - stories in my town that were fascinatingly intertwined.” It came easy, too. “Sometimes a record takes forever and ever to make and by the end you’re a nervous wreck; this wasn’t like that. It was like getting a massage,” he laughs. “It was really easy.”

Accordingly, it is an easy listen - one that evokes childhood exceptionally well - but intimations of a world beyond understanding spike its songs. “Until I was 17, Meriden was my whole universe,” Will explains. “It was a very fascinating thing, because... In a certain sense there’s a lot of safety, and a kind of idyllic life, but in another sense there’s this closeness to the community that’s really fascinating. As you get older you start to figure out that certain people are having affairs with each other. Or, if there’s a death. There was this 15 or 16-year-old kid who I really looked up to and idolised, a musician, and he died in a car crash. When something like that happens in New York City, I’m sure it devastates the immediate family and neighbours and friends, but when something like that happens in a town of 500, it alters the landscape forever.”

He left Meriden in his late teens, first to Minnesota and to college, where he describes feeling “a rising sense of panic” at his decision to put his artistic dreams on hold. “I had a kind of epiphany where I was like, dude, you should just follow what you’ve wanted to do all along. So, one of the guys who I played music with in high school lived in Texas, and another one of them lived in Wisconsin, and I figured it’d be good to get out of the frozen north, so I convinced him to dump his girlfriend - which I feel terrible about in hindsight.” (I express mild disbelief at this, to which Will assents.) “Yeah, I was really cold. I was just like... Yeah: we gotta go. She’s gotta go. So we moved down to Austin, Texas.”

It was 15 years before he made it back to his hometown. In the meantime Okkervil River were formed, while his father got a job in Western Massachusetts and the family moved away. Meriden isn’t near anything, he says, “So I just never went back. I think the more that I stayed away, the more it was locked in my brain as these isolated memories, floating on an island. When I went back and actually saw it, it was like... ‘Oh my God, I’m back on an island’, that in some weird way I thought I’d never come back to again. I thought if I came back that it would be so different I wouldn’t feel anything. That’s what set all these feelings into motion.”

When he speaks about the town - whether it be bumping into his fourth grade teacher that very morning, for example, who reminded him how he could never tie his ice-skates up properly, or reconnecting with childhood friend Aaron Johnson, his first ever bandmate at around the age of eight - it’s with an enormous deal of affection. He currently lives in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, where he moved to from Austin, Texas, and cites being closer to where he’s from as a (possibly subconscious) motive for coming back. The more reserved nature of the people is one thing - in contrast to a Southern penchant for hospitality that he never felt entirely comfortable with - but he also feels that he fits in better further north.

“My family’s still all around here. A lot of my family stayed in the same area, and I was a different kid in that respect, because I got much further away. Getting back home was really powerful. My grandparents, who I was living with when I was working on I Am Very Far, who I often go and visit, sometimes when I’m working - I’ve been visiting my grandfather a lot more recently, in hospice - they’re really the seed of my energy and inspiration, and so being able to be around them and be around the place where they’re from... I just feel like I’m more powerful in that area.” He laughs at that last, but it is interesting to hear him compare Williamsburg (“sort of the hipster capital of the world”) to a slower, more sedate kind of life. “You rediscover this old version of yourself,” he states - an idea that echoes throughout The Silver Gymnasium, despite an earlier admission that “All of it is filtered through the lens of where I’m at right now, and where I’m going to. As you can’t really go back. You can only really go back on the imaginary roller-coaster of a song, or a poem. Then the song ends and you’re left standing back in the present again. You only get a tiny little glimpse of it.”

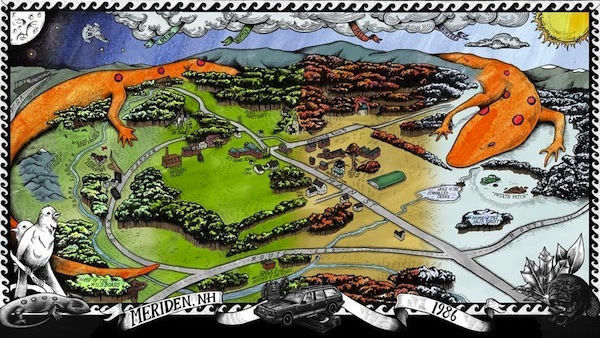

Okkervil River have a history of engaging, thoughtful promotional campaigns for their work, and among the projects Will undertook for The Silver Gymnasium is a trek round (mostly bemused) open mic nights (see above) he and Aaron made in the area, and, brilliantly, an ongoing, 8-bit style adventure game based around the LP that he created in conjunction with Eyes and Ears’ Benjamin Miles. The band’s longtime collaborator William Schaff also came up with a beautiful hand-drawn map of the town, which is Will’s favourite artwork to date. (Also above; interact with it via NPR here.)

We talk about a lot of things. Too many to get into this article, unfortunately: from the beauty of regional accents to why music sounds better in a car; the quaintness of the “nostalgic future” depicted by science fiction films of the late ‘70s and early ‘80s to the band’s searing Spanish-language version of ‘Westfall’. In discussing Will’s own writing, a surprising (or perhaps not that surprising) influence on The Silver Gymnasium becomes apparent: Kendrick Lamar, creator of his favourite LP of last year, good kid, m.A.A.d city. “It’s a really different record about childhood and about place,” he says, “But I really loved how conceptual it was, how immersive it was, and how you really felt like you were there. I loved how his character came through really clearly. The ambitiousness of it really gave me the strength and inspiration, I think, to point The Silver Gymnasium where I wanted it to go.”

I mention how I treated my family to that album while playing board games last Christmas, and how it didn’t go over entirely well. Warming to the theme, Will goes on: “There’s a lot of songwriters out there in the indie-rock world or the rock and roll world who have written off hip-hop, or they won’t even listen to it, or they’re very suspicious of it, and it’s otherwise progressive people who you think would be interested in it. To me it’s the natural last refuge of the songwriter who’s interested in words. We’re at a point right now in songwriting where the standards have loosened up a bit, and I feel like I hear a lot of writing where there’s a kind of pseudo-profound thing going on that’s not really borne out in the way the song is written. So you feel like... ‘You’re using these really big loaded elemental words and reaching for some profound thing, but I don’t buy it’. When you look back at the standards of where songwriting was at different times... If you’re looking for that: people in love with language, people telling stories in different ways, people choosing really interesting words, hip-hop has still got that going incredibly robustly and powerfully. For me it’s a natural refuge for people who are still looking for strong narrative and fun use of language.”

The Silver Gymnasium, though certainly slicker and more polished than anything in the band’s discography to date, is, as ever, an album very much in love with narrative, with words. It is littered with proper nouns and childhood recollections; songs nostalgic and sweet that flirt with a sense of danger and the unknown. Verbs of movement abound - throttling, hurtling, crashing, soaring - before the closing ‘Black Nemo’ eases up on the gas, tying up the record’s myriad threads in the process. Will expands on the kinetic nature he aimed to capture in its songs: “I think that that’s what you’re doing in life, you know? You’re shooting along. And a lot of the time when you’re a kid it seems like you’re in this kind of... oasis. It’s like the slow, slow climb of a roller-coaster. You think we’re probably just going to be climbing forever, then suddenly you get to this point where you’re looking down at this massive plummet. Once you’re going down the other side, that’s just as long as the climb, but it sure goes by - it sure feels like it goes by - a lot faster.”

It is an album that - in a very short space of time - has become one of my favourites of the band’s career. There are a lot of reasons for that; circumstance certainly played its part (as I feel it will for many listeners), as well as the surprise of something so different in tone to what preceded it. Ultimately, though, it’s down to the songs themselves, and how they paint a picture of a town, of a feeling; of a memory of a feeling, and how memory works. When I question Will about the darker themes that occasionally surface, this is his response. It’s not entirely in keeping with the spirit of the LP - which is a warm, jubilant listen more than it is anything else - but it’s as good a place to leave things as any:

“There are things like death; certain things that happen that are like a little foretaste of what you’re in for with life. I have this thing I’ve been thinking about recently, that if the first part of your life is like a comedy and the second part of your life is like a drama, then the third part of your life is like a horror movie. I do think that that starts to happen. I mean, it happens earlier to some people than others, but you get to a point in your life where people are dying, people you love are dying; people you love are suffering, horribly. It seems really unfair and meaningless, and you start to see the end of the line. It might be way off in the distance, or who knows? It could be the instant you walk out the door. But you start to see that end of the line; you start to see how the adults were trying to protect you all along. You thought that you were in this beautiful, safe play-land that was penned in, but that was because it was a very skilfully maintained illusion by all these adults who loved you. The reality there was danger, and sorrow, and deeply unfair realities of life, that were present all along.”

--

The Silver Gymnasium is out now via [PIAS] Cooperative/ATO Records on CD, cassette and double LP; visit Okkervil River’s official site here

The band play the UK next month:

Nov 27th, London, Islington Assembly Hall

Photo by Ben Sklar