On 13th July, Rain Dogs Revisited comes to the Barbican in London. Over the next three days, Drowned in Sound presents a series of pieces reevaluating and celebrating this classic Tom Waits album....

If you’ll permit me a few minutes, I’ll tell you a story. A few years ago, on one of my frequent sojourns from Manchester to Newcastle in the name of a long-distance relationship, I stepped on board a National Express coach for the trip across the Pennines. As always, my most valued possession for such occasions was my iPod, tucked precariously under my arm as I flashed my crumpled ticket and scrambled into the nearest vacant seat. But what to play? I flicked through my list of albums, considering and rejecting potential suitors until my click-wheel fell onto an album that pricked at my interest.

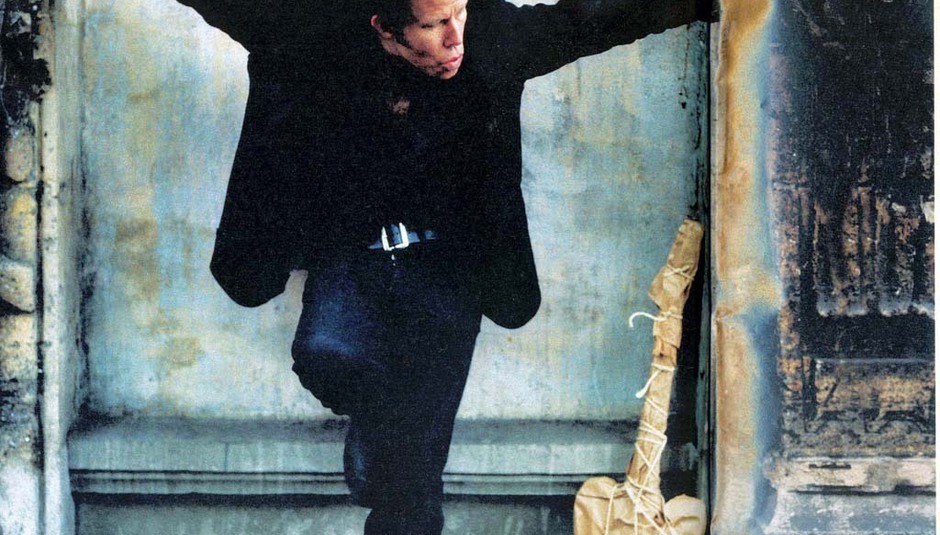

Rain Dogs – Tom Waits

The album had sat on the digital shelf since my friend Nick bought it for me a year or two earlier. Ripped, Added, Forgotten; not once had I been possessed to listen to it since. I was vaguely familiar with Waits but certainly not what you would consider to be a fan. But that day, as farms and hills rolled out of the early morning mist, it just seemed to be calling out to me. So I settled back and pressed play.

What I instantaneously learned was that when you listen to Tom Waits, you take residence in a new world. A world with strange, grotesque characters looming out of the walls at you from all directions. A world where nothing makes too much sense for more than a transitional minute. A world of David Lynch, Terry Gilliam and Federico Fellini montages set to music. I considered the image of “a one armed dwarf, he’s throwing dice along the wharf” during ‘Singapore’. I took note of the elastic, rhyming couplets bouncing back and forth through ‘Clap Hands’. I recoiled, then listened in fascination to the Kurt Weill Carnival of ‘Cemetery Polka’; wheels twirling pantomime-style in my mind as the background figurines came to life in gruff unison. After a few tracks I was intrigued, but within my limited experience, it was somehow how I expected Waits to be: inscrutable and challenging but hard to love. And then I heard ‘Time’. My expectations were floored in the face of such breathtaking, ethereal beauty. And just as you fall in madly love with someone you suspect you really should steer clear of; forehead pressed in wonder against the coach window, I fell head over heels for Tom Waits.

Waits’ 9th record, released in September 1985 is for me, the point at which anyone should start their journey into the dark, twisted yet beautiful world of his music. That isn’t specifically because it was my gateway, but because it contains a perfectly weighted balance of all the elements that make his music so challenging, fascinating and irresistibly jolting for a music lover. The endearing wisdom is to start off at the records predecessor: 1983’s Swordfishtrombones. I always think this to be because that was the album where Waits started to plough headlong into the world of the weird, taking on obscure rhythms, arrangements and vocal constructions (though in reality, he’d been morphing into increasingly odder shapes since 1976’s ‘Small Change). But whereas Swordfishtrombones is a fascinating document of an artist in transition, Rain Dogs is a triumphant mastering of so many unique and disparate strands of sound; largely unmatched in popular musical history with The Beatles self-titled 1968 record being the only obvious comparison. What makes Rain Dogs so comprehensively engaging is that despite spreading himself over so many styles of music and instrumentation, Waits appears in total command of his styles, themes and delivery. The cunning can copy and paste. The genius learns, embellishes and triumphs.

Rain Dogs sprawls majestically. The title refers to domestic dogs losing their natural scent tracks back home after a heavy rainstorm: an appropriate moniker for an album which continually casts its eye on downtrodden New York characters cast adrift from normality by events beyond their control, huddling together for an unlikely and unsteady camaraderie. It perfectly encapsulates the point where Waits’ penchant for beautiful, cinematic and poetic ballads confronts the sonic invention and envelope-pushing that he garnered from being introduced to Captain Beefheart, Kurt Weill and other diverse musical manuscripts by his new wife Kathleen Brennan. The influence of the latter is vital in understanding Waits’ development and confidence in relocating his sound into previously uncharted territory: "My wife's been great” Waits admitted to Playboy Magazine in 1988. “I've learned a lot from her. She's Irish Catholic. She's got the whole dark forest living inside of her. She pushes me into areas I would not go, and I'd say that a lot of the things I'm trying to do now, she's encouraged" The influence of Brennan in catalysing the dramatic reactions occurring in his mid-to-late 1980s records resulted in the opposing edges of his music becoming deeply and wonderfully embedded within each other on the album, glowing white-hot with friction.

Take the first half of the album that I described before. You rattle - pinball style, from one inn and doorway of a darkened alley of rogues and miscreants before suddenly, the window of heartbreak opens into the stunning emotional left-right of ‘Hang Down Your Head’ and ‘Time’. Waits is well known for being obtuse and ramshackle. What many don’t realise is that he’s arguably the finest writer of ballads in the last 30 years. He understands tenderness and he understands how to use it effectively without treading onto mawkish ground. A perfect example is the magnificent ‘Downtown Train’, a song which, on that first album listen years ago, I looked ahead and already knew from the Rod Stewart cover version. What did I expect? I expected gruff, angular and prickly. What did I get? A masterclass in how to do a shining melodic anthem while all the time comprehensively eschewing cliché: the art of how to write a so-called “big song”. This is Waits all over. He’ll work you hard, but he’ll reward you in spades afterwards. And for every moment that horrified people look over at you and mouth “What the bloody hell is THAT?” there’ll be another song that you could play to your grandmother and have her nod in sage approval. But with Waits being Waits, there’s always something positioned just that little bit off centre to hold the interest of the curious and the demanding. Listen to the growls and marauding brass strutting their way around ‘Tango ‘till They’re Sore’. Sway to the taut, clipped funk of ‘Walking Spanish’. And admire the Chinese Tangram puzzle intricacy of ‘Diamonds and Gold’, slotting together obtuse pieces with consummate ease. These are the hallmarks of a composer and musician at the pinnacle of their art: experimenting wildly while remaining coherent and gleefully expressive.

The pivotal addition to the roving group of musicians behind the album’s tapestry of sound was guitarist Marc Ribot, whose razor-wire treble lines act as the perfect foil to Waits animalistic mumbles, scats and growls and provides apt musical reflections on the song narrative. A perfect example is the angry, kaleidoscope guitar solo on ‘Jockey Full of Bourbon’, like a drunkard attempting to aim a gun

through the hazy fury of inebriation. Also featured on the album is Rolling Stones lead guitarist Keith Richards, adding his characteristic Telecaster bite to ‘Big Black Mariah’ and ‘Union Square’ (according to Richards, Waits informed him of the style he wanted him to play by wordlessly gyrating in front of him). The forceful, poly- rhythms of Michael Blair and Stephen Hodges add a jarring, unsettling tone to the proceedings with thick, sensual percussion running scared from skeletal marimba. Yet much of the real atmosphere is laid down by the dark, sweeping curtains of New Orleans brass that flit about in the wind of the record. Waits had experimented musically for many years, but it was on this trio of records that he fully began exploring the way that a record’s sound and feel could be tailored to perfectly fit the subject matter. Lyrically, the album contains some of his most vivid images, ranging from the rambunctious rag-tag characters permeating the gloom of ‘Singapore’ and ‘Cemetery Polka’, through to his chiselled-in-dirt poetry depicting scattered human wreckage found in the titular track, and so profoundly expressed, as Larry Taylor’s upright bass dances around in the background, within the spoken words of ‘9th and Hennepin’:

“And all the rooms they smell like diesel

And you take on the dreams of the ones who have slept here

And I'm lost in the window, and I hide in the stairway

And I hang in the curtain, and I sleep in your hat

And no one brings anything small into a bar around here

They all started out with bad directions

And the girl behind the counter has a tattooed tear

One for every year he's away, she said

Such a crumbling beauty. Ah,

There's nothing wrong with her that a hundred dollars won't fix”

Within the album (as in so many of his records), one of Waits greatest skills is the ability to draw you pictures with his words, gradually sketching in the details without ever resorting to pretension and cliché. Some of the lyrics from ‘Time’ are some of the most striking and evocative lyrics of his entire career, including this incandescently beautiful image taken from the final verse:

“Well, things are pretty lousy for a calendar girl

The boys just dive right off the cars and splash into the streets

And when she's on a roll she pulls a razor from her boot

And a thousand pigeons fall around her feet”

By the end of the record, through the pistol smoke, whiskey and tears, you feel that Waits emerges triumphant. The glorious cacophony of accordion, striding gleefully into a marching Dixie jazz band parade on ‘Anywhere I Lay My Head’ could be seen as either a celebratory party, or an upbeat funeral procession. Either way, Waits seems to have found a realisation waiting for him on the other side:

“Well I see that the world is upside-down

Seems that my pockets were filled up with gold

And now the clouds, well they've covered over

And the wind is blowing cold

Well I don't need anybody, because I learned, I learned to be aloneWell I said anywhere, anywhere, anywhere I lay my head, boys

Well I’m gonna call my home”

Rain Dogs, within all its ramshackle yet perfectly aligned mayhem, is arguably the album where Waits’ penchant for ironically juxtaposing the grim and the gorgeous of society is presented in its most vivid colour and shape. As I was soon to discover following that memorable day, having stepped off the coach at Newcastle into a new and beautiful world of music, Waits has never made a bad record, and there are some that would challenge Rain Dogs for the title of his finest album (Mule Variations is equally as good, if not better in terms of overall quality). But in terms of creating a musical landscape where the freaks, the criminals and the crazy share ground with the heartbroken and sensitive under a sky of brilliant invention, it is a record like no other. He’s an artist where it isn’t simply a case of putting a record on and letting it spin ambiguously in the background. He’s someone who metaphorically strong-arms you into attention. But it’s worth every second of introspection. And in my eyes, Rain Dogs is the door into the oddly-lit attic of his mind that is most perfectly shaped for you to slip inside. And if you can stay strong amongst the weird shapes and sounds for just a little while, you’ll probably never feel the need to step out again.

Rain Dogs Revisited come to the Barbican Hall on 13 July 2011. Directed by David Coulter, with St. Vincent, Arthur H, The Tiger Lillies, Camille O’ Sullivan, Stef Kamil Carlens, Erika Stucky. The performance is part of the Barbican's summer music festival Blaze: www.barbican.org.uk/blaze