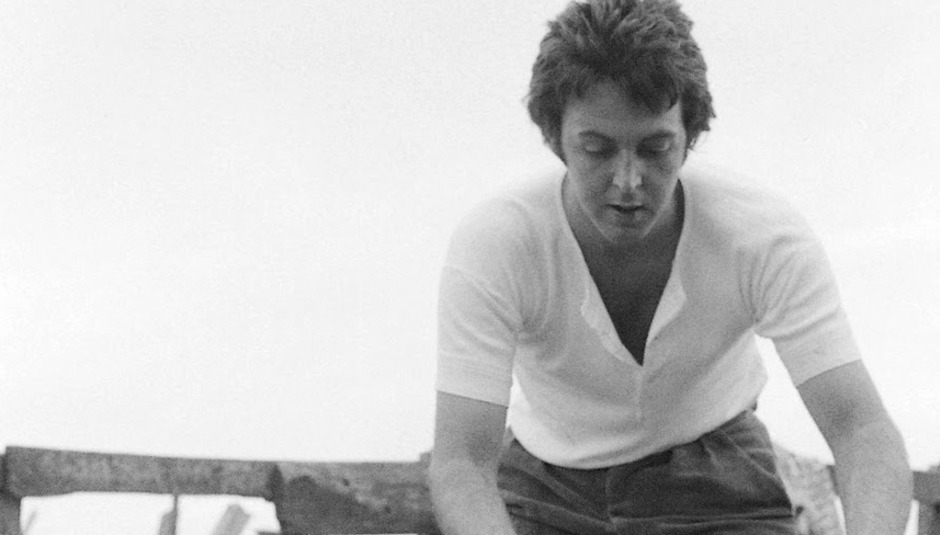

Last week, we published the first part of DiS' exclusive interview with Paul McCartney, conducted by Mansun's Paul Draper. Before we get into the second part of this conversation - which touches on everything from Sir Paul's motivations, meeting John Lennon and playing drums on 'Back in the USSR' - Paul Draper shares a few words about his experience...

I spent a fascinating afternoon with Sir Paul McCartney last week. As a life-long fan, I had few things I had been dying to always ask him. We discussed the reissue of RAM, his much underrated and now reappraised record with Linda McCartney from 1971 (just listen to 'Monkberry Moon Delight' to see how good this record is and sounds.) For me, it was fascinating to hear Paul discuss the origins of prog-rock. However, for Sir Paul to pick up a guitar while just the two of us are sitting there and to start strumming away at jazz chords, which he still doesn't seem to know the name of, it made him suddenly a very human figure. A living legend indeed.

I have to say RAM sounds mighty fine remastered and reissued in this tuneless age, its a record that catalogues his exit from The Beatles, shows all that he's learnt in those Beatle Years and is a fine historical document of his Journey from Beatles, to Scottish recluse to New York recording artist. Time has been kind to RAM because of the depth of melody of the songs which you can come back to no matter how many times fashion turns. I wanted to know a few things for myself from Sir Paul, about where he got his songwriting ideas from, the prog-rock influence on 'Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey' and why he chose to play an Epiphone Casino guitar, my favourite guitar ever made! I hope you enjoy Sir Paul's answers as much as I did. Thanks to Sir Paul and all at Soho Square for making it a memorable day. Ram On!

Paul Draper: When you were working on RAM, I read your recording sessions were pretty regimented, did you find that once you had a family and you were putting your work schedule into your life, that it was different than when you first started out, when you had the hunger, when you got that deal with Parlophone? I wondered, did that change of process, when you got to RAM, make it feel more like a regimented job?

Paul McCartney: I don’t think I ever allowed it to be a regimental job, but it changed with the family just because early on you were single, so you would be going to clubs and you would be hearing all the soul records, like you do when you’re that age, you know? You begin to hear loads and loads of influences, all the American stuff: Phil Spector, Motown, Stax, Blues, all that stuff would come piling in and you’d just nick little bits of it, you know? You’d be inspired to play in that style or something. Then I think later, when you’re not going to all the clubs, when you have settled down a bit I think that’s what alters it.

It’s never been a job though for me. Never let it be a job! People say to me ‘ooh, you work really hard’ I say ‘well, it looks like I do because you see a picture of me in South America, in Mexico City, then the next week you’ll see me somewhere else, and it looks like I’m working real hard, but I actually have quite a few days off!’ The thing I say to them, and it is a bit facile, but I say ‘we don’t work music, we play music’ and I really have got that thought firmly in my head. When I get onstage with the band, I’m ‘playing’ and it makes a big difference so we’re not working, we have fun you know? It takes a bit of energy. You’re knackered after it but not during it. People say ‘you were onstage for three hours’ and girls always say ‘and you don’t even have a drink of water’ ‘yeah?’ ‘well, how do you do that?’ and I say ‘well, firstly, can you imagine The Beatles in the middle of the set going “She loves you Yeah! Yeah...” wait a sec, hang on, glug, glug, glug...’ we didn’t do that! I go as far as to say ‘we didn’t drink water where I came from!’ I mean seriously, as a kid, we never drank water, it was lemonade, tea, whatever. Nowadays they say it’s like eight gallons a day you’re supposed to drink, but anyway...

I just enjoy it. I'm lucky because the audiences are brilliant, so it is not so much a fight anymore.

Can I ask you about guitars... my all-time favourite guitar is the Epiphone Casino, through either an AC30 or a Fender Deluxe...

Oh yeah, baby!

...and, that’s the guitar solo sound on ‘Taxman’. There’s some photographs of you with your sunburst Casino in the box set of RAM. I just wanted to know if that was a guitar that you were using a lot around that period?

I got that while I was with The Beatles, basically, because I love Jimi Hendrix, and I’d seen Jimi down the Bag O’ Nails down the back of Liberties off Regent’s Street. It was a club we used to goto because the clubs were our pubs. Instead of going to the pub at seven thirty ‘til ten thirty we’d go eleven thirty ‘til two. So I’d seen Jimi down there and I was blown away. I wanted to get something that would feedback. So I went down to Charing Cross road here [Sir Paul points out the window across Soho Square toward Denmark Street] to ‘the mecca’. Where it just used to be all guitar shops. We’d usually just go and window shop.

Anyway, I went into the shop and said to the guy that I wanted something that would really feedback and it said ‘well, this one will’. It had a hollow body and that was the reason I got it originally. I used it for the ‘Tax Man’ solo originally, and ‘Paperback Writer’ because it just... like you say, through a Vox it just gave a nice little dirty noise. I use that on stage now.

---

---

I just wanted to ask about Linda [McCartney]. The album’s credited to you and Linda, what was Linda’s role in songwriting and the process of it and more than that, helping you to get back up and write as a solo writer for the first time?

I look back and that was really the most important role, getting me to write and getting me motivated. When I would sit down and write, she was often there. We’ve got some bonus tracks and you can hear her just harmonizing a little bit. So she was really there to give little suggestions if I get a bit stuck. Like ‘was it long-haired lady’ or ‘longer baby lady’ ‘oh yeah’ ‘ok’ or whatever. It was a good feedback situation, but a lot of it was just motivation. So I’d do the song and I probably, certainly, did most of the work on the songs, but she’d throw in ideas. It’s always good to have a second sounding board. So I thought, in the end, she should get credited, so it was the both of us.

On the bonus disc you’ve got a very long version of ‘Rode All Night’, which is you sort of jamming and singing, and it reminded me of the way you did ‘Helter Skelter’, which was to do a really long thing and then to edit it down. The fascinating thing about it is there’s no bass on it and that really reminds me of how you would record - like we were talking right at the start of this conversation about recording onto a four track, and you would overdub the bass line later. Hearing that, being a fan, I was fascinated to hear something without the bass on it. Is that because of the fact you were jamming and that was an idea that would maybe be developed at a later stage, edited, bass added, etc?

The thing about anything without bass, was that when we first started off, in the really early four track days, we pretty much played as a band, but then as things developed, what would happen would be, like, let’s say something like ‘Lady Madonna’, I would of developed that as a little piano part, and singing part. So I’d bring that to the guys, and it wasn’t anything I could hand over, I could say ‘now you play the piano, and I’ll go on bass’. So I would always play it on what I’d written it on. Sometimes the guys would play bass. John played bass on ‘Let it Be’, and ‘All You Need is Love’, I think he played the bass.

I think we had to do it that way, because, for instance, anyone else playing the ‘Lady Madonna’ thing wouldn’t get the feel. George Martin was a good pianist, but he wouldn’t get the feel. It was essential, like, to get the feel, so I’d have to do that, sing it, and then everyone would be kind of done, and I’d sometimes stay behind and work on the bass part, and sort of try to fit it in. It did piss ‘em off a bit, the guys, you know, because we had been used to playing as a unit, and I was bass... when there’s ka-chang-ker-ker-chang-chang and there’s no bass, you haven’t got the bottom on your record, so, [errr] I was a bit embarrassed about that, but it worked out ok, once you got over that embarrassment. That meant I had a lot of time to consider, like, the final thing that would be put on there would be my bass or maybe next to final, if we put some saxs on or something.

So that’s why that’ll happen. Even on guitar, the feel, would be something I’d want to get down.

So something like ‘Back in the USSR’ you’re playing to your own feel there, because you’re reported to be playing, everything?

I’m not playing 'everything'. I’m playing drums, and I think bass, and probably guitar, but I think the guys are in on it, George and John are playing along. It’s such a difficult thing, you know - well, you’d know, being in a band - it’s kind of difficult because if you know the way a thing should go in your own mind, and if you’ve written it... our kind of unwritten law was whoever has written it kind of produces it within the band. So if it was John’s song he’d say what he wanted and we’d all play for John, we’d be his sidemen, if it was my song, they’d be mine, if it was George’s, we’d be his. So yeah, that sort of did happen, but in ‘Back in the USSR’ I’d heard the drums being a certain way, and Ringo wasn’t getting it, and it was really embarrassing, because the last thing I wanted was to go ‘let me have a go, let me see if I can get the feel, I’ll show you how I want it to be’. So you’d sit down, and go 'dum-dum-doff', kind of like that [Sir Paul air drums] and then Ringo would sometimes go ‘why don’t you do it then?’ slightly pissed, probably, ‘why don’t you do it then?’ and I’d be like ‘you sure, you ok with that?’ you know, that’s the band thing. So I ended up doing the odds and sods on tracks, like the ‘Taxman’ solo, I’d just got my Epiphone Casino, it was howling away, I was grooving and I’d say ‘I just want something like this’ [makes high-pitched guitar solo noise] and I kind of had a feel, and George would say ‘well, you do it then’.

I also wanted to ask you about your motivations for RAM, and writing songs. Am I right in saying you went in with about 23 songs for the recording sessions in New York?

Yeah.

I know from my experience, when we were talking about the structure of recording, you go in and you’re there with other people, but to write a song is a really lonely process. You have to get up in the morning and it’s only yourself that can make you do it. What was your motivation for writing RAM, because it was pre-Wings and you weren’t in a band with other people to depend on you, and then your motivation for writing them first early Beatles' songs, did that change? Was something inside you?

Yeah, it came in stages, like phases. The first thing was writing a little bit of stuff on my own in Liverpool, meeting John, and he said ‘I’ve written a couple of songs’, as it come up in conversation and I said ‘so have I!’ So it was like ooh, that was the first person I’d ever met who’d said that, so we said ‘let’s get together’. So that started. Then everything then was written by the two of us. We’d meet up, we’d write something. Up until a certain stage where we got a bit more freedom when he moved out to Weybridge and I was still living in the city [London] with my girlfriend then, so I’d have a day when I’d get a bit of inspiration. Or something like ‘Yesterday’, I just woke up with that in a dream, so I’d write that and he would be in Weybridge writing a song like ‘Nowhere Man’. We’d kind of get together after that, so that next stage, where we’d start to write individually and then we’d get together, like ‘Eleanor Rigby’, I remember I kind of write that in London and I’d get with him and sort of say ‘I need the second verse, we’ve got to have this other character, I can’t decide what to call him’ but I’m calling him Father McCartney and John said ‘That’s great!’ and I said ‘Nah, I can’t call him my name’ it would just embarrass me, and that’s my dad. So we got the phone book and we looked up M-m-m-Mc-Mcar-Ma-Mackenzie ‘ah, that’ll be good!’ We’d polish off each other’s work, and that was kind of the next phase.

Then there was a phase when each of us would just write completely individually and then just bring the song in and say ‘what do you think of this?’ and that was it.

After The Beatles, when I was no longer writing with John, it went back to that, it was just writing on your own, but the motivation is the love of it, that’s what it is, so it doesn’t really matter, you know, I’ll wake up some days, and I never really have a problem sitting down with a guitar, there’s always something, you know? I mean, I can do it now. It may not be good, but I can get something together. I love the fact I can do that. They talk about a gift and all that, but the more I go on I realise that it is, like, a gift. We used to say like, you know, ‘he’s got the gift of the gab’ or ‘he’s got the gift of music’ and when you think of it as a gift, it really is very special. So I feel very privileged because not everyone out in that square and can do that, in fact, there's probably hardly any of them walking around there can do it. You can do it. And so, it’s like a magical skill that I’ve somehow locked into since I was at school, you know? I’ve got this thing going around all the time, so that’s the motivation, it’s just the love of it, you know? As you say, some of them come easier than others. Sometimes you can sit down and it just falls out, and those are normally the best. I wrote one for my wife, ‘My Valentine’ off the new Kisses on the Bottom album, and that just kind of just wrote itself almost, you know? It was just there, for the taking.

---

---

Click here for part one and more from DiS' recent RAM week...