“She is very neurotic. She is very concerned about what everyone else is doing.” Kele Okereke looks fairly concerned himself right now, as if he's quietly divulging a secret that has left him tortured inside for months. “She's just really worried.” he says. “It's everything. We can't change the bins, any new thing in her space freaks her out...”

We're discussing his young bull terrier, Olive, and he's experiencing some guilt. “I feel bad because she spends a lot of time alone. Luckily I'm home at the moment so I get to hang out with her a lot. It seems to be such an interesting life, being a dog. She just sits around in the kitchen and barks and watches you move but that's kinda what we wanted. We wouldn't want it to get upset if we weren't in and to get lonely.”

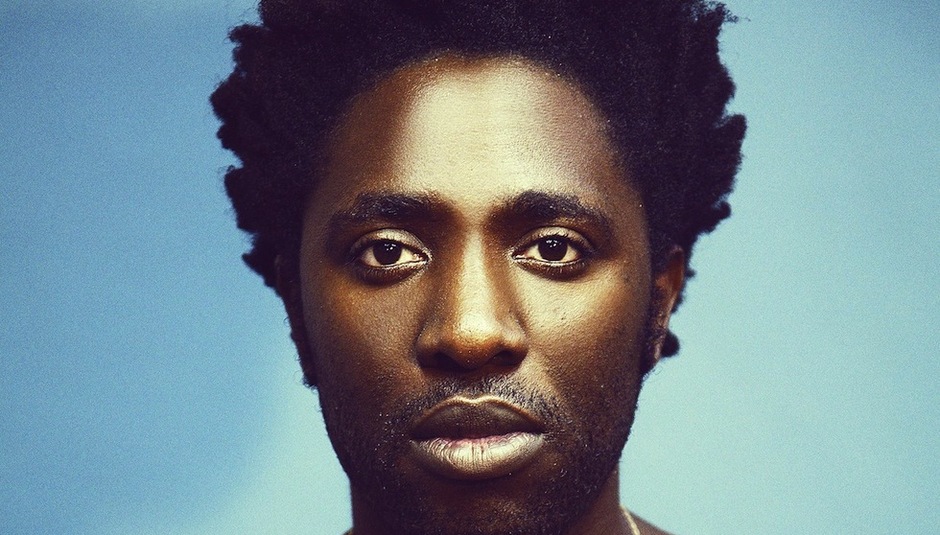

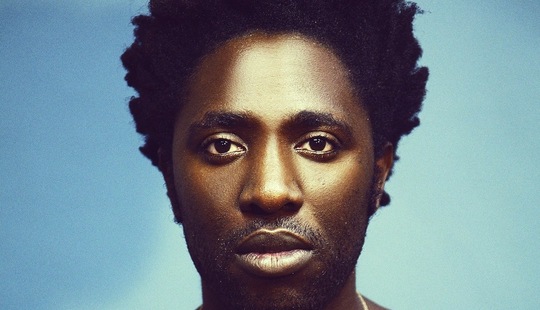

We wouldn't usually start interviews with an exchange about bull terriers (it's not exactly typical DiS fodder) yet it is a side of Kele that we don't get to see very often. Or at least we don't read about it. The tricky interviewee status he has acquired may or may not have been justified before but when we meet on a miserable Monday evening he is perfectly considerate and engaging, as I would suspect he is most of time. In fact, he is so accommodating it takes three attempts to answer the first question because he wants to find somewhere secluded so he can think clearly. “I realise I've got to do a good interview for Drowned in Sound” he explains. I practically melt into a giant puddle of relief the moment the words leave his lips.

We've shut ourselves away in a tiny doorway upstairs at The Macbeth in Hoxton to escape the noise of the stage being assembled, where he will be performing later as part of the 'JD Rocks the Macbeth' series. Casually dressed in a loose-fitting black t-shirt and red jeans, he sits upright on a small windowsill whilst I awkwardly loom over him, perched upon a rickety old book shelf. It's as cosy as you can get for an interview (except perhaps Paula Yates' bed in the The Big Breakfast house) which suits us quite nicely as we weigh up the potential benefits of a dog psychologist for Olive's various anxiety issues, as well as his new release, Trick, his second full-length solo outing.

It's his 6th record in 9 years, including his work with Bloc Party. It's an impressive rate, especially in comparison to the indie generation from which Bloc Party emerged, who have typically either disbanded, never to be seen again, or whom are languishing perilously close to the tall cliffs of obscurity. It's fairly prolific, I suggest. “Yeah, I guess so. I actually did an interview and Jessie Ware was doing one too when I met her for the first time. We were talking about it, because she was just about to release her new one, and she asked 'does anything change the more records you release?' and I said, ‘Yeah, you start to care less'. I joked, obviously, I don't care about the music less but, y'know, this sort of thing, the promotion and touring [he shakes his head] it's just a part of the process.”

It's the release day for the album and he tells me it's also his birthday (33, in case you are wondering). He's meeting friends for dinner later to celebrate before the show. I apologise for not knowing in advance but he reassures me that he's not that bothered. “I actually feel like they're a little over rated anyway, I always seem to be working on my birthday.” Given the amount of music he's released in the past decade, I can believe it's true. Does he keep up a regular routine to keep himself productive?

“I think the routine starts to kick in when I'm touring” he suggests. “When Bloc Party tour we tend to tour for at least a year and a half. We always had short attention spans so we would always start working on new material whilst we were touring. I think that mind-set became ingrained; that whilst you are promoting a record you don't have to be a jukebox, you can still be creative. That was the attitude we kept. That's why we always released new music towards the end of an album campaign because, I guess, I like it. I like the creative side more than any other. Playing shows is nice, it's rewarding but, for me, the magic really happens when we are pulling something out of the air and you’re making something that didn't exist, so that's mainly why I've done so many albums in that amount of time.”

The ideas for Trick started to evolve between tours with Bloc Party for the their last album, Four, in 2012. He purchased an electric piano and starting creating the initial sketches. “I don't really play piano so it was a way of teaching myself how to play.” He recorded them and starting bouncing them back and forth with his producer. “I knew what I wanted the record to roughly sound like but there was a lot of to-ing and fro-ing, a lot of starting again on ideas. Like the lead track ‘Doubt’, it started off one way and it ended up in a very different space but that's the beauty of collaboration that you will work with people you trust and they can show you stuff that you wouldn't have already anticipated. So although it was a solo record I was still working with others. It wasn't just me locked in a room. I think if that had been the case it would have been a lot different.”

His primary influences from the record came from playing DJ sets, which he does regularly around the world, and a desire to recreate the energy of a club on to a record. It has resulted in an eclectic mix of sounds on the album; Garage, 2-step and RnB all creep into to it's nocturnal, predominantly house-based core. It's also comes imbued with a sense of yearning. With song titles such as 'Stay the Night', 'Like We Used To' and 'Hotel Room', there is a palpable sense of longing and desire.

More than anything else you feel convinced of Kele's joy and zeal for electronic music. This is not just a passing curiosity for a bored singer in a rock band. He does concede, however, that a lack of harmony after the strains of touring with Bloc Party informed his mindset at the time of writing. “Bloc Party were touring heavily and as I said we always tour for like a year & a half and we'd been doing it for just over ten years and... [sighs heavily]... it's like what I said earlier that with the music it's a very specific routine that you experience every few years of your life. When we toured Four we'd been apart for two years and then we made that record and toured it and a lot of things that were problems, a lot of the issues we had, were still there. Definitely still there. So I think maybe I retreated a lot into myself. I think that's where the enjoyment, that's where I started to feel the excitement about djing because that was something I could do by myself. So to me it was a different world, I guess.”

Though the musical overhaul is most noticeable difference on Trick, this creative switch also affected his lyrical approach. Whereas the wordplay with Bloc Party was densely packed - Marc Burrows' recent review of Trick reminded me of this particular gem: “At Les Trois Garcons we meet at precisely 9 o'clock. I order the foie gras and I eat it with complete disdain” - on Trick, it's spatial and simplistic which, I suggest, seems to fit with the new sounds and structures he was playing with. He nods in agreement. “Yeah, I think you’re completely right. With the early Bloc Party records I wrote the lyrics separately to the music and then at the end of the process, I'd try to jam them together, so it was like a mission. With Weekend In The City and Intimacy it was like a real mission to make things work. It really wasn't until I made The Boxer, those songs were constructed in a studio environment, so I was able to build a song around a phrase. It wasn't like I made lots of music and I had to fill it in, [with Trick] the process was kind of inverted. I was able to get something that I felt worked vocally and form a song around it. I really enjoyed that process because it meant that the lyrics started to inform the music as opposed to two separate entities. With this record I was able to re-evaluate constantly, which is something I was always resistant to in the beginning but now I really see the beauty in just living with something and letting it take a ride as opposed to trying to force a square peg into a round hole, y'know?”

In interviews around the time of his first solo album, The Boxer, Kele suggested that his first foray into solo work was a bit of experiment to see if he could write a solo record. Having been used to collaborating with other musicians for all of his professional career, going solo presented a new challenge. With this in mind, does Trick present a more defined vision of Kele 'the solo artist'? He says it's more circumstantial that this. “I think it was a vision of me as a solo artist in the two years I was making the record. If I was gonna make a solo record right now I don't think it would sound like this. Luckily because I have the opportunity to express myself presently, I feel that there isn't any sense in looking backwards. Whenever I’ve release a record there's a familiar pattern. You love it so intensely when you're making it, because it's yours and it's only yours. Once you get it out there, once you share it with your management and your record label and the fans, then it becomes something which isn't yours at all any more.”

Given the vast differences between the latest Bloc Party record, a straight-up rock record and his electronic solo outings, I ask whether he feels more at home in one particular form or genre. He veers slightly off topic, not that I mind, to confirm that a new Bloc Party record will be at the forefront of his mind for future projects.

“I must say having finished this record, Trick, this solo record, I am very excited about the idea of making music with my band, or with other people. [With the solo work] it’s a lot of staring at a computer and editing stuff together, and that's cool, but I am yearning for some spontaneous creativity. But I am very lucky that still now when we come together, I am still reminded of the musicianship that the band has. So yeah I'm excited about making another record for sure. That's what I feel I want to do next.”

Just as he casually drops this information into our conversation, he receives a phone call from his friends who are waiting outside. Whilst he goes off to find someone to let them in, I am presented with a bottle of Jack Daniels from the sponsors to give to Kele as a birthday present. Given he confessed to me earlier that he's not really a fan of the stuff, and I've already admitted that I didn't even know it was his birthday, it seems like an awkward imposition but upon his return he smiles and seems grateful. “Thank you, that's very kind. I'll take that home with me. That's the only present I have received today actually.”

And it's this side of Kele, quite bashful and sincere, that really strikes me during our conversation. It reminds me of this article about the nature of interviews, and how the narrative of an artist is largely shaped by people who simply don't know them, which results in an image of the artists which they themselves probably do not recognise. So I ask Kele how he feels about the narrative around him and how he copes with what is written. From someone who has been through the mill, his response is both frank and illuminating.

“I guess I learnt the hard way at the start of my career. I guess I got a reputation of being a difficult interviewee but I don't know. How did I deal with that? I guess I didn't. I stopped reading that stuff. I think that's the point. I stopped reading interviews. I realised that I didn't need to engage because anything you've read would feel like a caricature of your personality. That's what I felt in the first year when I was reading it and I thought I don't need this. People are coming to our shows and buying our records, I don't need to concern myself with what's going on around me, so long as I am honest about my output and motivations. I feel that so much of news is ephemeral. There's going to be someone else that their going to be talking about next week. It just keeps the balls going. I think there is this desire for news which is far outstripping the content. I'm lucky that I don't have to engage in it. When I finish this show I'm gonna go home and I'm going to look after my dog and then have a day off and get ready before I go to Germany on Wednesday. I don't have to engage with it. I think it might be different if you are at the start of your career and everything is exciting but I think at some point you have to learn to leave that stuff outside your door. It's just going to drive you mad.”

And if that's the choice; between going mad through reading articles about yourself or dealing with a neurotic bull terrier - then I think know which one I would pick. Now where did I put that number for the dog psychologist...

Trick is out now via Lilac/Kobalt.