Wherever you stand on Lana Del Rey’s first three records, you couldn’t really claim she gave too much away on them.

What’s harder to discern is where exactly she draws the lines between her actual private life and the version of herself that she projects through her music. That is, if it can be considered ‘herself’ at all; back in 2012, when ‘Video Games’ had blown up and Born to Die topped the charts around the world, certain sections of the press broke the news that she was actually plain old Lizzy Grant and that this wasn’t her first musical rodeo as if it was some earth-shattering revelation that a successful musician had once been anything but, and that an artist might take a stage name rather than go by their own.

There have been points at which her songs have felt honest enough, usually in a way defined by their simplicity; ‘Blue Jeans’ was open and earnest, the nods to gangsters and James Dean cute. At the other end of the spectrum are the likes of ‘Money Power Glory’ and ‘Fucked My Way Up to the Top’. Even if she’s skewering greed, materialism and underhand tactics on them, she’s still doing so through the eyes of Lana Del Rey the character - the ingénue still in thrall to Hollywood’s seductive power even as she’s being corrupted by it, telling the sort of stories that Naomi Watts’ characters from Mulholland Drive might have if their respective naïveté and bitterness had met in the middle.

Her best efforts came when it felt as if we were getting a little of the woman behind the mask, even if it was wrapped up in the grandiosity she’s so fond of; ‘Young and Beautiful’, for instance, a gorgeous lament of the pressures women face as they age that might be the high point of her opening trilogy of records. Such moments were generally few and far between, though, and the upshot is that the same three ideas cropped up so commonly that there was precious little room for anything else; beauty, melancholy, and thoroughly toxic relationships. Incidentally, the debut album by Portland newcomer Alexandra Savior, released back in April, was such a flagrant Del Rey imitation from start to finish that it even came with a title that pithily sums up the latter’s entire persona - Belladonna of Sadness.

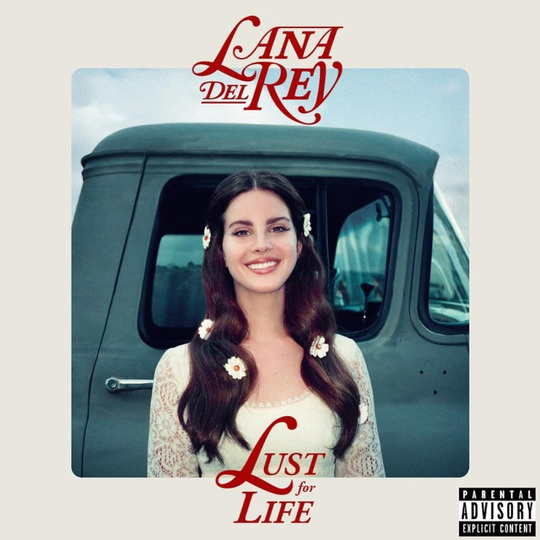

That’s precisely why the cover art for this fifth LP caused such an online furore when it was unveiled earlier this year; as on the front of Born to Die, Ultraviolence and Honeymoon, she’s pictured with a decidedly American vehicle, this time a pickup truck. Her trademark pout, though, has deserted her. Strikingly, she’s instead grinning like a Cheshire cat. For Del Rey, that didn’t just hint at a new direction - it suggested a wholesale ripping up of her own rulebook, given that carefree happiness was frankly anathema to the image we’d become attuned to.

Lust for Life doesn’t ultimately deliver anything quite so dramatic, but it is enough of a departure from what’s gone before to suggest that it heralds the opening of a new chapter. For the first time, we see Del Rey acknowledge the world around her, both musically and thematically. That’s not to say that this isn’t identifiable at a hundred paces as one of her records, because it absolutely is, but up to this point, she always seemed as if she was trapped in amber, not of this time either aesthetically or sonically, preferring to melt back into the warm embrace of the Fifties and Sixties and that limited palette of lyrical ideas. Even when she began to play with this a little on Honeymoon - inverting the male gaze with ‘Music to Watch Boys To’, or referencing ‘Space Oddity’ on ‘Terrence Loves You’ - she did so coolly, with arm’s-length control.

Not even Del Rey, though, is impervious to the political turmoil of the last couple of years. Six months into America’s new nightmare, she’s found she can no longer wrap herself in the flag, literally or figuratively. It’s this shift that forms the crux of the record’s most important tracks, all of which crop up in succession around halfway into its sprawling 73 minutes. Her detractors must have rolled their eyes into the backs of their heads when the track listing for Lust for Life revealed a song called ‘Coachella - Woodstock in My Mind’, given that the former event’s rampant commercialism is the antithesis of everything that the latter symbolically stands for today and that Del Rey, wearing flowers in her hair on the album’s cover, could easily be posited as its poster girl. She knew better, of course. In fact, it’s an affecting account of her watching over similarly-garlanded young girls at the festival and fretting for their free spirits in the face of such a turbulent world.

On a similar tack, ‘God Bless America - and All the Beautiful Women in It’ was apparently written before the women’s marches that stood as such a powerful rebuke to the new president in January, but would surely have soundtracked them had it been out by then; Del Rey doesn’t wring her hands or posture politically, and instead delivers a heartfelt treatise on what sisterhood and solidarity mean to her. She rounds out her state-of-the-union triumvirate with ‘When the World Was at War We Kept Dancing’, which might be the bravest of the three given that escapism is a dirty word to those of the mindset that a minute not spent resisting the creeping spectre of fascism is a minute wasted. Still, her long-standing penchant for fantasy has never served her better.

You get the impression, too, that she reasoned that if circumstances beyond her control were going to drag her into the modern world whether she liked it or not, then she might as well stick around to see how else it could it bleed into her music. So many of the sonic flourishes on Lust for Life are rooted firmly in the present, and the debt that she owes to hip hop weighs heavy for much of the opening half. That’s not just because A$AP Rocky and The Weeknd turn up as guests, to good effect and utterly redundantly respectively; a fair few of the cuts here sound as if they started out as beats that were made to be rhymed over before Del Rey, with no little care, broke them to fit her own mould.

If you hadn’t heard the rest of the album, you’d probably assume that ‘Summer Bummer’ was Rocky’s own, with Del Rey guesting. Before that, the one-two of ’13 Beaches’ and ‘Cherry’ provides the first evidence of her foray into urban territory; the sparse percussion of the first suggesting drama in much more restrained fashion than we’ve come to expect from her, and the textured, trip hop ambience of the second confirming her arrival in the twenty-first century. ‘Coachella’ unfurls over a stuttering trap track that’s subtle enough not to notice on first listen, and a wall of unforgiving bass towers over ‘In My Feelings’. Set against the golden age glamour of her earlier work, these are developments that feel positively raw.

Even so, the tried-and-true Del Rey remains in attendance on Lust for Life, and it’s perhaps on that front that the whole thing could have been pared back a bit - 16 tracks is too many. Her past self pops up on both sides of the fence; ‘Groupie Love’ is lyrically exactly what you’d guess and could have fit on a past LP if not for Rocky’s assured contribution. ‘White Mustang’, meanwhile, comes with no such caveats and would not have raised eyebrows had it turned up on Born to Die. Occasionally, old and new click together, like on ‘Beautiful People Beautiful Problems’, which sounds like something that a hypothetical Lana Del Rey song title generator would produce and which features an obvious influence of hers, Stevie Nicks. That she holds her own against her hero, though, speaks to her never-higher confidence.

The progress that Lust for Life demonstrates wouldn’t really amount to much more than a shuffling of the proverbial deck for most artists, so it speaks to what a strong identity Del Rey has spent the past five years carving out for herself that they feel like such profound changes. In the end, she remains enigmatic, and probably without an obvious frame of reference amongst her contemporaries. What she isn’t, though, is inscrutable - not any more. Lust for Life represents the thawing of the ice queen we thought we knew, and the strange death of her American dream. The warmth and humility revealed beneath are all the more thrilling for how well they were kept under lock and key. Human after all.

-

8Joe Goggins's Score