'All the great performers that I’d seen who I wanted to be like, all had one thing in common - it was in their eyes. There was something in their eyes that would say "I know something you don’t know." I wanted to be that kind of performer.'

For Bob Dylan, a man who subsists wholly on a diet of cigarettes, allegory, myth, and amid 50 years of purposely subverting his tectonic influence and genius in notorious interview sparring, such a pure vignette of truth is shocking to the point of absurdity. Only months after being publicly anointed the 'spokesman of a generation,' monsooned screams of “Judas!” attended a haggard Dylan as he emerged in a battling pose onstage in Manchester 1966, signaled to his aghast backup musicians, and commenced what Bruce Springsteen would later call a 'snare shot that sounded like somebody’d kicked open the door to your mind.'

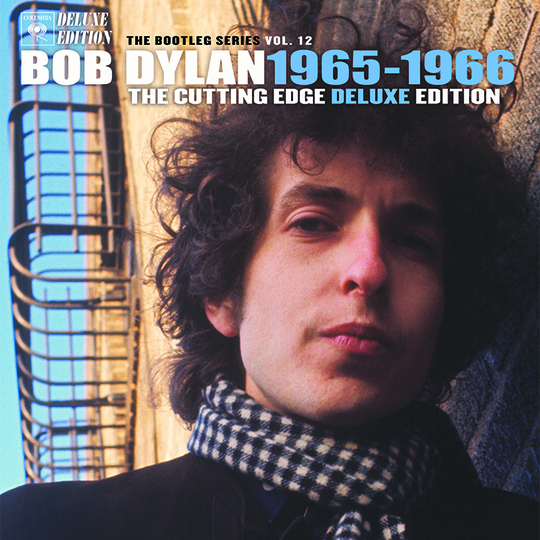

Notwithstanding that mountainous moment in rock'n'roll history, he then commenced dodging incensed “go home!” chants, plunged his sweat, blood, and might into each barbed piano stroke while ridiculing the audience with frenzied alacrity on 'Ballad of a Thin Man'. A battle to the death as Dylan audibly jousted with enraged mudslingers thoroughly indoctrinated in the gratuitous notion that a donned-in-all-black Dylan had entirely abandoned his 'protest song' roots to wear the black hat of sellouts. Affixing a penetrating gaze onto an eclipsed audience, Dylan recognised that in little over a year he had engulfed an entire stratosphere in the stalwart vacuum of his squinted eyes. It is those same riveting eyes that are donned mercilessly on Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde - three ingenious masterstrokes that forever aligned him with history and completely galvanised the music of The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, and hundreds of exhaustive books, documentaries, and films.

The Cutting Edge zeroes in on arguably the most enthralling chapter of the fabled Dylan saga. Although tidy, shampooed anecdotes surmise that Dylan’s creative cloudburst in the mid-Sixties was a divinity-laced cosmos of talent, brilliance, and amphetamines, The Cutting Edge discharges simpleminded perjury for a gloriously divergent truth - in that entombed within each awe-inspiring track is the skeletal remains of a frantic perfectionist combing through each note, kneading each couplet, and shuffling between a continuous ensemble of vocal intonations. Just beyond the eternal compass of hand-polished upshots long ago committed to memory, it is the heuristic Dylan wayfaring through time in the perpetual search for musical sublimity that truly accentuates the most engrossing component of Dylan’s twelfth official bootleg instalment.

Like the golden stanzas themselves, the logistical backdrops of Dylan’s studio sessions are impossible to separate from the recordings, and the escapades originate in the since storied sound-booths of Manhattan’s CBS Recording Studios. Connoisseurs already firmly grasp the esoteric notion that no two performances of his material ever sound quite alike, and “Love Minus Zero/ No Limit” wafts between worlds of traditional folk and glides through netherworlds of epic serenades, never forfeiting even a hint of its emotional intensity in all its breathtaking mutations. With Dylan’s lyrics singularly functioning as the cardinal impetus for literally decades of scholarly debate and New York Times bestsellers, every word seems to radiate with newfound awe and wonderment as they sail from Dylan’s lips, almost as if he is gauging the precise range of their gravity for the very first time. The acoustic guitar on 'She Belongs to Me' urgently registers in sparse, modulated doses, with Dylan occupying the more hushed intervals with scribbled enchantment.

One of the most illuminating facets of The Cutting Edge is what an unequivocal testament it is, both to the layered ingenuity of the session musicians and Dylan’s self-ordained composing pursuits. The sheer beauty of Dylan’s poetics account for resplendent sketchings in their own right, but the canvass truly crests at full tilt and titillation when the instrumentation is infused with the unifying supervision of the end product. Spearheaded by his trusty harmonica, 'Like A Rolling Stone' repeatedly slingshots from a nimble, danceable waltz into the formidable, reverberating tour de force that dwells supreme in the mainstream consciousness. But in the case of 'It Takes a Lot To Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry' it is Dylan’s intrinsic decision to temper the figurative and literal accelerators to opt for a more symphonic aura that is a fascinating spectacle to behold. He furthers his experiments with tempo metamorphosis in a similar fashion on 'Mr. Tambourine Man', allowing a prominent backing tambourine to vehemently buttress his stirring wails and transpose the popular existential folk hymn into a rollicking tune gifting a drum-like cadence.

Multiple outtakes of Dylan’s infamous, venerated ode to vitriol 'Positively 4th Street' will certainly warm both the hearts and heads of devotees, but absolute climatic enterprise occurs when Dylan sets his sights on the material that would eventually comprise the lion’s share of Blonde on Blonde. The irksome, universal toil of shuffling heaven and shoveling earth to procure the historic compounding of Dylan’s choice palate with the clairvoyant panache of the Nashville session players resulted in what is largely opined to be his finest artistic consummation. The immaculate exploration process unfurls in a gregarious endowments, paradoxically dispatching both primordial and postmodernist affectations on one Dylan’s most heroic flights of symbolic fancy on 'Visions of Johanna'.

Although most disciples are guilty of emptying their pockets for the chance to hold captive 'unreleased' gems like 'She’s Your Lover Now' and 'Can You Please Crawl Out Of Your Window?', the bewitching phenomenon of hearing them in their infant stages demands this 111-track extravaganza of a compilation. As Dylan continues to advance in age and wrinkle count, the untamed allurement of his virtuosity exponentially emits transcendental flair with the passing of each year. More so, as his travels continuously chaperon him along uninhabited and potentially perilous artistic terrain, his incised boot imprints are sometimes the only evidence a mortal of his stature is actually among us. Quite possibly the only safe method to confront Dylan is in the music itself. Anything that could be misinterpreted as a stare is begging for viperous consequences, because to scrutinise a Dylan photograph is to recklessly confront omnipresence personified - a portrait that will indeed 'look back' with a puncturing gaze and eternally murmur: 'I know something you don’t know.'

-

10Kellan Miller's Score

-

10User Score