There is a strong sense in which even attempting to write 'a review' of an album like Kendrick Lamar's second album, and masterpiece, To Pimp a Butterfly, is foolhardy.

It's one of those pieces of art that comes along something like once a decade, so layered with meaning, so knotted up with intent and resonance, so of-its-time yet treating issues and themes that can span eras, that I am still discovering and uncovering different meanings, references, and picking my way to an imperfect understanding of it, despite having had it - literally - on repeat, daily, since its release last month (was it just last month? It already feels like music I've lived with for years).

It's the sort of album that deserves – no, demands – to be really listened to, worked out for oneself, and - in case this is all making it sound like homework or duty, god forbid - relished and delighted in, in all its jazzed up, funked out, soulful, loud, proud, angry, sad and beautiful glory.

So all I really want to do, here, is share with you a few of the reasons why I think this is a beautiful and very important release. And hopefully urge you to experience it for yourself and decode/unlock its manifold wonders.

To Pimp a Butterfly is a concept album with many themes, which interlock and overlap. It isn’t a straight narrative, instead leaving the listener to fill in some of the gaps for herself. So threads running through the album include the perils and temptations of fame (personified and referenced several times as Lucy aka Lucifer), the importance of home vs hotel rooms and life on the road, weightier concerns like black-on-black violence, US race relations, African-American role models, the history of black music, slavery, America…

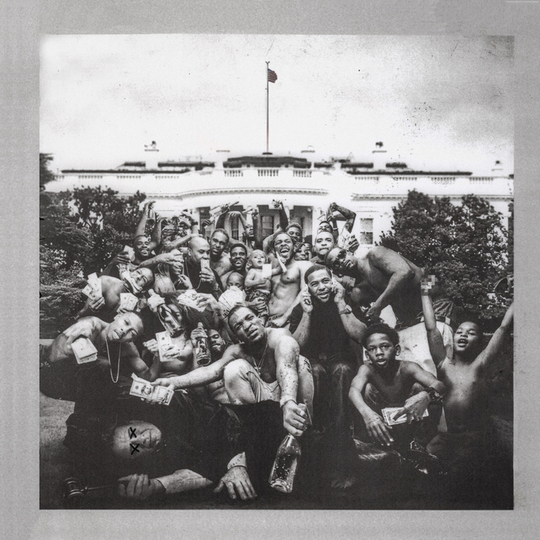

All expressed in Kendrick’s quite astonishing dressing-up box of voices and personas, we take a journey with him that begins, on opener Wesley’s Theory, with a few bars of black pride affirmation, courtesy of a Boris Gardiner sample (“Every nigga is a star”) before getting serious as Kendrick, aided by guest appearances from Dr Dre, Josef Leimberg, Thundercat and George Clinton no less, sketches out the conflicts between the disconnect of fame (“when I get signed, homie, I’mma act a fool”) and realness or loyalty to your roots (“I’mma put the Compton swap meet by the White House”). Like a Greek chorus, Thundercat dolefully interjects: “We should never gave niggas money, go back home”, while Dre bursts in, as is Dre’s wont, to provide a pep talk/slap down: “…remember, anybody can get it / The hard part is keeping it, motherfucker.”

The Temptation-of-Kendrick-by-Lucifer thread sees Satan, or the personification of the evils of fame, represented by 'Lucy', an insidious, wheedling character who is sometimes cast as Kendrick’s 'first girlfriend', rearing her alluring yet ugly head to beguile the rapper with promises of wealth: 'Lucy gon’ fill your pockets (…) I see you want me, Kendrick.' The peculiar but arresting 'How Much A Dollar Cost', which reads like a parable, and in which Kendrick meets a crack-addicted homeless man who might in fact be God (it’s – deliberately – not clear), shows one possible opposing force to Lucy’s evils. Another, in the album’s other main duality, is the power of 'home' or Momma, to counteract the negative influences and evils of hotel rooms, fame, wealth, false friends and grasping lovers.

So 'Institutionalized' sees our narrator contemplating renouncing the stage to get back to his hood, while describing the dissonance and clash of the two environments, as experienced when he took some of his “homies” to an awards show. The disorientation that these contrasts have clearly caused is really effectively expressed, in auditory terms, by the creepy, woozy, just-coming-round-from-a-fevered-dream sound of the Hispanic housekeeper’s knock on the door attempting to rouse him in 'u'.

These contradictions and the competing pulls of different worlds leave Kendrick open to many hypocrisies. Perhaps the most valiant parts of the album are where he acknowledges not only the hypocrisy of his peers in the fame game – the rapper who allegedly uses a ghost writer that he alludes to on 'King Kunta' (Kanye?), Wesley Snipes’ tax evasion ('Wesley’s Game'), Samuel L Jackson’s appearance in 'Django Unchained' 'i' – but also a fierce take-down of his own double standards when it comes to black-on-black violence. The excoriating 'The Blacker the Berry' starts out promising to expose himself as “the biggest hypocrite of 2015”, and ends with the confession that, despite his virtuous, politically-conscious stance on many issues and justified anger at police violence, he is still a contributory and culpable player. “So why did I weep when Trayvon Martin was in the street”, he asks himself, furiously, “When gang-banging makes me kill a nigga blacker than me? HYPOCRITE.”

It’s one of the album’s key and most searing moments.

Other important facets of the album accrue and gently layer, rather than bludgeon. A recurring micro-story first appears in 'These Walls'. “I remember you was conflicted”, Kendrick recounts. “Misusing your influence / Sometimes I did the same.” The thread is picked up again at the song’s end, and once again in Hood Politics, until it becomes a story all of its own, told in a remarkably economic way, of depression and alienation in hotel rooms, homecoming and the lack of easy resolutions to the circumstances that the artist finds himself in.

But along with the violence, self-doubt, negativity and disgust come some huge and inspirational doses of pride and positivity. The whole album sometimes sounds like a celebration of many ages of black-led music – from the quite astonishing free jazz that complements Kendrick’s flow so well that it’s a marvel ('For Free?' where his words tumble out in a freeform jumble like the music; 'How Much A Dollar Cost', beautifully swelling up again when Tupac laughs during the interview segment of 'Mortal Man') to the bass-heavy funk of 'King Kunte' and 'Hood Politics', from the sensual R&B of 'These Walls' to the hard-egged ragga that opens 'The Blacker the Berry', and what sounds like a James Brown tribute in the wonderful 'i'.

Lyrically, too, 'i', is a terrific helping of inspiration. The (simulated?) live performance starts with an MC introducing “the number one rapper in the world”, who unashamedly sings “I love myself”, before breaking off in dramatic style to intercede in an offstage argument. Exclaiming “Not on my time, not while I’m up here… kill the music! We should save that shit for the streets”, Kendrick launches into a motivational rant – almost a sermon – about embracing “the little bit of life we got left” with joy and music, before joining the “dead homies” or countless comrades lost “this year alone”. He then goes on to offer his own take on “the infamous, sensitive N-word”, and how it can be reclaimed as “N-E-G-U-S” (“description: black emperor, king, ruler”), sounding energised, almost messianic, desperate to get his words out, pleading: “wait, listen! (…) Let me finish!”.

As the album draws to a close, Kendrick weaves in a spoken-word poem (“it ain’t really a poem, I just felt like it’s something you probably could relate to”) calling for unity in the black community: “Just because you wore a different gang colour than mine’s / Doesn’t mean I can’t respect you as a black man (…) If I respect you, we unify and stop the enemy from killing us.” This then segues into a remarkable imagined dialogue with Tupac, Kendrick’s questions and responses interspersed with Tupac’s actual words from a 1994 interview with the late artist. This in turn then leads in to Kendrick sharing and explaining the central metaphor of the album – the pimping of the butterfly by the caterpillar – with his idol.

It’s a hugely affecting and arresting interlude and an astonishing way to close an album. But this album astonishes, shocks, inspires, entertains and enthrals on just so many levels that it is a fitting ending.

What does it all boil down to? To Pimp a Butterfly is an album with more to say about contemporary America – race relations, the country’s foundations on the slave trade, the vast inequalities dictated by money and skin colour, the dysfunctional relationship between the sexes, fame and more – than you might read in many so-called Great American Novels. A review like this can really only glance on the most obvious themes that have seemed to emerge, without really capturing the full beauty, intricacy and brilliance of the work. This is an important – a very important – piece of work that will stand the test of time. It’s also an utter blast to listen to and live with.

-

10Jude Clarke's Score

-

10User Score