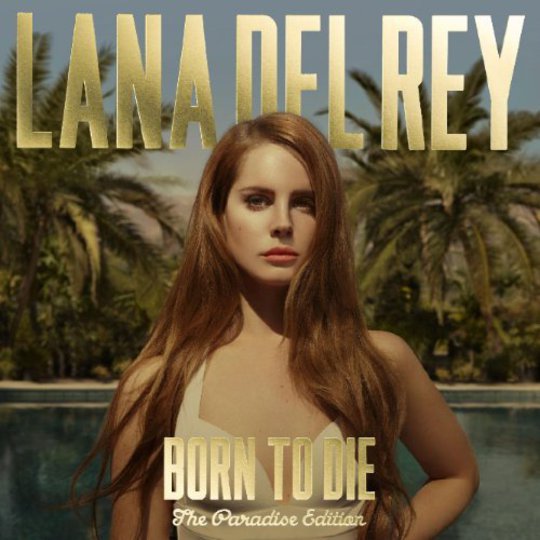

With the closing days of 2012 rapidly drawing into sight, where do we stand now on Lana Del Rey? The general thinking prior to - and continuing after - the release of Born to Die appeared broadly split into two camps: those considering her to be exhibiting a bruised, seductive movie-star persona with a series of deliciously dark pop tracks from the unlit side of the Hollywood sign. And those that considered her a cynical piece of record label fodder and dolled-up industry window dressing. Or in failing to concoct anything so articulate, uttering something appertaining to the shape of her lips. This polarisation became one of 2012’s defining pop music opinions – it became remarkably difficult to predict who fell for the charms and who turned away in distaste. Lana Del Rey - the Marmite artist of 2012.

As for me? I hate Marmite. Loathe the stuff. But I’ve a genuine love for Born to Die. It has its flaws, sure. The dreary fallen angel whimsy of ‘Carmen’ sums up precisely the unfocused drift that critics often use to malign her and on songs such as ‘Dark Paradise’, the caricature extends beyond our empathy. And certainly, there are times where the lyrics steer far too close to the rocks and razor edges of cliché for comfort. But for all of these moments, there are always quite spectacular counterpoints. The stunning twists and swoops of ‘Off to the Races’. The ethereal elegance and climactic shudders of ‘Radio’. And of course, the heart-stopping film noir perfection of ‘Video Games’. Which a year on from release, has lost precisely none of its majesty.

So why do we need an extended Born to Die - The Paradise Edition? Normally, I despise these things. Reissue a popular record with a few extra songs just in time for the critical lists and Christmas sales and then KER-CHING! What makes The Paradise Edition relevant however (though it’s still a repackaging, whichever way you look at it) is that within its added chapters, the whole Lana Del Rey figure: that composite character she builds her songs on, emerges more completely. A starlet caught in the headlights. The tortured, neurotic beauty of a Tennessee Williams play. And as such, the new tracks work to complement the character, fully exposing the dark underbelly of the music. It’s like the reality after the reel spins to a cease. If Born to Die was the script-defined character, then Paradise shows the darker routes through reality once the director yells “cut”.

Of the new tracks, three (‘Without You’, ‘Lolita’ and ‘Lucky Ones’) were actually found on the expanded edition of the album’s initial release, and still seem a little too much like an effort to graft excess epilogues and a faux happy ending onto the fittingly melancholy original tracklisting (though ‘Lucky Ones’ is a delectable companion piece to ‘Video Games’). From the rest, it’s those epic and bloody dissections of the used and knowingly abused starlet chasing the American Dream that still most engage the senses.

The sweeping corners of ‘American’ and the night-air escapism of trailer single ‘Ride’ almost come over like a reflective, feminine take on Springsteen, filtered through a haze of the cigarettes, whiskey fumes and exhaust smoke. Yet when she switches tempo, the results can be even more striking, most notably on the shimmeringly beautiful ‘Yayo’ which is shot through with uncertainty, 4am bloodshot-eyed regret and a sense of everything only a heartbeat away from collapse. And her take on ‘Blue Velvet’ – played completely straight – is simply sublime.

Yet for so much of the second disc takes on a noticeably more orchestrated feel. In comparison to the clatter and storm of Born to Die, the music here is more considered and richly teased out. Her lyrical themes may remain fairly limited in scope and a source of annoyance to some, but there’s intelligence, a maturity and an admirable sense of restraint in so much of the music that can’t be ignored entirely. The lost little girl might just be growing up. And above all, learning. And while Paradise still has its moments of frustration (‘Bel Air’ never quite manages to achieve the Sufjan-esque melodic complexity it aspires to, while ‘Gods and Monsters’ simply drags), like Lady Gaga’s The Fame Monster, it takes a polarising debut artist and brings a new degree of respect and expectation into the equation.

As for the initial album, there’s nothing more I can say that wasn’t expressed far more eloquently by Krystina Nellis in her original review. But it certainly is telling that there remains interest in Lana Del Rey's music after the initial clamour and hype. And for those overly concerned on critiquing her through the prism of her looks, image and interviews, I can’t help feel that there’s a purpose behind it all. Like all great pop and cultural standpoints, the image and the aura is important. And while I’m still on the side of those believing that Lana Del Rey is about so much more than that stylised, Technicolor frame she seems to dwell within, there’s also the need to understand and appreciate that the background is often as important as the subject in front. The image and glamour of Lana Del Rey is symbiotic with her music and the structure and function of her songs cannot exist without the faded Hollywood glamour her character seamlessly drifts in and out of - a portal to the past in the midst of the iPhone generation. And once the makeup and dresses are put away and the last of the champagne is drunk, so many of these songs still stand tall; long after the regrets and recriminations of the morning after. “Elvis is my daddy / Marylin’s my mother” she croons on ‘I Sing The Body Electric’. It would certainly explain an awful lot…

-

8David Edwards's Score