If one thing characterises the work of David Lynch it’s his critique of the 'false-self systems' that pervade our lives. Take Eraserhead, where the bourgeois pretensions of slum-dwellers are almost more grotesque than their physical deformities, and Jack Nance cracks when he watches the mother of his child transformed into a breeding machine. Take The Elephant Man, where the gawking spectators are sped up into squawking homunculi while John Merrick retains the only trace of dignity. With his last film, Inland Empire, Lynch attacked the machinery of capitalism on a global scale, presenting the Hollywood leading lady as the apex of desire we fixate on, ignoring the pyramid of bodies beneath; when Laura Dern slips into a parallel world of sex-traffickers, we see what the Hollywood fantasy masks: a world fuelled as much by desire as the need to subjugate someone else. We tell ourselves it’s bearable because there might be a way out; a Heaven to escape to. Thing is, the 'ascent into Heaven' sequences never get any less cheesy, from Twin Peaks to Mulholland Drive. Are we supposed to believe the things he has Julee Cruise sing to us in these scenes – that strange synthetic angel?

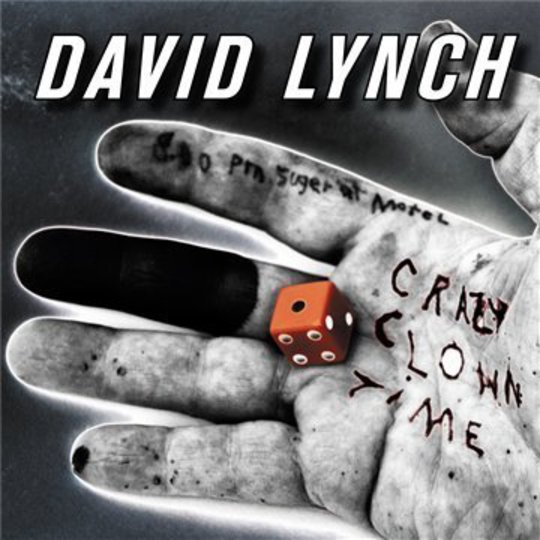

And so we come to Crazy Clown Time – when the squeaky voiced Mr Lynch steps out from behind the dream-pop puppet Julee Cruise, who used to literally hover above the stage, on strings. According to Lynch himself, the depression that led to him taking up transcendental meditation in the early Seventies felt like “wearing a clown-suit I couldn’t take off” which doesn’t bode well for Lynch and Badalamenti fans expecting another Floating into the Night or The Voice of Love (the albums they wrote for Cruise). A solo album makes you think 'intimacy' and 'honesty' but Crazy Clown Time makes you think Lynch is just trading one false-self for another to point to the difficulty of finding the real. Sure, it seems almost yawnsomely obvious for Lynch to fixate on clowns, but if we think of clowns as Lynchian it’s only because of a single scene in Blue Velvet, where Dean Stockwell’s dapper Ben makes Dennis Hopper’s psychopathic Frank cry.

Clowns are that odd species of performer we laugh at (but nervously) for their revenge on human pretensions we wanted to be true: on female pretensions to be sublimely 'other'; on aristocratic pretentions to be more than hairless apes (back when everyone wore make-up); on humans to be more than crudely painted puppets of Fate. Clowns are what Lynch makes all of his characters at some point: the classic Lynchian shot a too-long-held close-up (according to David Foster Wallace), when the human face comes to seem like a mask, and you wonder what’s underneath.

But this is a supposed to be an album review, right? Well, yes and no, because did you seriously expect to forget who it is? Over the course of 70 minutes and 16 tracks, Lynch’s combination of lap-steel, processed vocals, and subliminal synths is genuinely captivating, and varied enough that even if “Mr Lynch” were a complete unknown plucked from the slushpile, he’d get favourable notices somewhere. In a world where Lynch-the-director never was, the mysterious 65-year-old making his debut would be compared to Daniel Johnson or Jandek for his crazy clown vocals, while others would mention Swans’ epic Soundtracks for the Blind, with its loops of sound from you-dread-to-think-where, interspersed with the recollections of traumatised people who never quite name their trauma.

The default setting for the music is most accurately: The-Roadhouse-scene-from-the-Twin-Peaks-movie (you know: the absurdly under-rated Fire Walk with Me), which means it’s difficult to imagine yourself anywhere else while you’re listening – anywhere but on the road leading to the Black Lodge, where Killer Bob prowls around, looking for girls’ skins to wear. Track by track, you find yourself directing films in your head to accompany each of these sketches, and you know Lynch's doing some of his best work here – except inside your head, this time. As ever, the characters should be caricatures – clowns and puppets – with their names like 'Pinky' and 'Stone', but as you inhabit their heads, you never quite learn what they want, and their lives continue, uncannily, on, after their songs end; much the same way the sounds teeter on the brink of representing life.

Arguably, it’s no bad thing to treat this as an extension of Lynch’s work as a director because you can appreciate his departure from, say, Bergman or Fellini: that his sound design and use of music may be the greatest in the history of cinema, whether or not you’d place him above the European masters in other respects. This is what makes for an enduring album in its own right, rather than a fans-only curio, and it shouldn’t be a surprise because this isn’t Lynch’s debut, anyhow: it’s a logical summation of 40 years of work, including the Eraserhead soundtrack, and the Industrial Symphony. Only in a few places does this come close to Lynch and Badalamenti’s songs for Julee Cruise, but when it does it’s gorgeous (‘These Are My Friends’), even if the 'friends' sound like the occupants of the Red Room.

Happily, Lynch’s Ibiza floor-filler, ‘Good Day Today’, is a one-off pastiche of vapid chart-friendly sentiments, and while we could have had a few more straightforward songs like the Karen O-graced opening track (‘Pinky’s Dream’) it’s not missed once Lynch hits his stride.

The first half is hypnotic, droning blues that works more as ambience punctuated with snatches of sleep-talk (close to Slint spin-off The For Carnation). After a seven-minute Kraftwerk-style interlude (where a vocodered Lynch recites a found-poem, jumbling together dentistry and mysticism), the final six songs are immaculate. The title track brings all of this together, with a bleary glimpse of a party just as drunken debauchery is about to turn into a murderous orgy, and the fact that one processed voice is responsible for the orgasmic sighs and the dog-barks that might be cries of fear makes this fractured mind even more disturbing. Yes, it sounds like you’re now entering Bluejam, but Lynch discovered the place, and instead of quitting cinema to make an album that’s being called his debut, it sounds more like he’s coming home.

-

8Alexander Tudor's Score