Forty years ago this week, Neil Young entered a makeshift studio on Santa Monica Boulevard in a state of deep depression and alcoholism and, in that single session, recorded the majority of the darkest album of his (or possibly anyone’s) career.

Coping with the recent deaths of roadie Bruce Berry and Crazy Horse guitarist Danny Whitten, Neil had seen heroin kill his closest friends, and he wanted to sing about it. That gloriously messy collection of songs about death would eventually be released as Tonight's The Night two years later. Neil’s own father Scott once described the album as “a man on a binge at a wake,” but that doesn’t quite do it justice.

Beyond being emotionally broken Young was also in terrible physical shape, having just finished the disastrous Time Fades Away tour he had developed a serious throat infection, brought on by ninety dates of alcohol abuse and falsetto.

As a Britpop-obsessed teen in the late nineties, probably while looking for a Graham Coxon interview, I came across an interesting list in Q Magazine – 'The Fifty Darkest Albums of All Time' (I since can’t find any actual evidence of this list, I guess someone forgot to tell the internet).

Second on the list was Tonight’s The Night (pipped to the gloomy post by Joy Division’s Closer). Back then I assumed all “depressing” songs had to be slow introverted ballads in the mould of Radiohead’s 'Street Spirit' or Spiritualized’s 'Ladies and Gentlemen...'

On first listen, Tonight’s The Night didn’t sound introverted at all, in fact it sounded positively joyous - the band were playing fast, and not fast like punk, fast like rock and roll. You can’t dance while lamenting your existence! It sounded like the band were having fun, sort of, in the same way that sometimes getting drunk and smashing stuff can be fun.

But of course, desperation can not only be expressed through ethereal arpeggios and precisely arranged fifty-piece orchestras, it’s often released through singing what’s on your mind, in any key you want, and bending guitar strings until they break.

The record is Young’s sixth “studio” album, although like the vast majority of his fifty album back catalogue, it was recorded live without overdubs. The vinyl label was black, not the usual Reprise orange, and it doesn’t sound like Neil Young. Whether through tequila or grief, Neil’s voice on this album is sometimes unrecognizable; it’s bluesy and lower in range. The tracks have no banjo and few harmonies - it’s bar-room blues, sloppy and soused. It’s also rough, angry, sometimes dissonant and often deliberately shambolic.

At the time Neil was more than happy to shed his folky image. He had recently refused to continue to record country-rock, despite Warner Bros. requests, after the phenomenally successful Harvest,

“Heart of Gold put me in the middle of the road. Traveling there soon became a bore so I headed for the ditch. A rougher ride but I saw more interesting people there.” Young famously wrote on the Decade liner notes.

That led to The Ditch Trilogy - three records that would be called “lo-fi” today about desolation and the blues - Time Fades Away, On The Beach and Tonight’s The Night.

While his peers (Fleetwood Mac, CSNY) were spending millions of dollars on big name producers, overdubs, choirs and string-sections, Neil recorded everything live, in a basement, in one take, in the middle of the night. The song 'Roll Another Number' was written there in the studio in that same session, and recorded immediately.

By all accounts it was a dingy scene. Photographer Joel Bernstein visited, “It was like doing a documentary on nocturnal animals pulled out from under a rock, they looked like rodents when you shined a light in their eyes.”

Drummer Ralph Molina explained the band’s preparation; “We’d just get to a point where you get a glow, just a glow. When you do blow and drink, that’s when you get that glow. No one said ‘Let’s go play,’ we all just knew it was time. We never talked about what anyone was playing, who’s playing what part or any of that kinda shit. It was so fucking emotional.”

Neil also tried to describe it, “When I first started the record, I didn’t know what the hell I was doing. But I did get into a persona. I have no real idea where the fuck it came from, but there it was. It was part of me. I thought I had gotten into a character – but maybe a character had gotten into me.“

The album starts and ends with two versions of the same titular song. A piano led blues number that Young wrote in his head without an instrument, and on which he doesn’t hesitate to sing about what’s on his mind.

Bruce Berry was a working man he used to load that Econoline van.

If you never heard him sing, I guess you wont too soon

‘Cos people let me tell you, it sent a chill up and down my spine

When I picked up the telephone and heard that he died out on the mainline.

The anger embodied as Neil spits in the words “died” and “mainline” is far away from the fragile warble of 'Old Man' and 'Heart of Gold'. That furious proclamation of a friend’s surprise death is then followed by a soothing three piece harmony repeating the title – “Tonight’s The Night”, as though angels have dropped down to reassure him that it’s okay, his can release his demons and move through this tragedy among his friends that are still alive, tonight.

Elsewhere on the album one of the most prolific songwriters of all time is seemingly too beaten up to write anything original. He rips off The Rolling Stones’ 'Lady Jane' and confesses to it, tired and alone at a piano, in a serene moment amongst all the chaos…

I’m singing this borrowed tune

I took from the Rolling Stones

Alone in this empty room

Too wasted to write my own…

I hope that it matters.

The song ends and something strange happens. A live recording of 'Come On Baby Let’s Go Downtown' rips apart the tranquility, with none other than Danny Whitten on lead vocals. The source and subject of the surrounding darkness, the corpse at the drunken wake, Neil’s dead band mate, is dropped in like a ghost in a live recording from a year before his overdose. Like a cruel joke Neil and Whitten sing together ecstatically about the good times.

Then seconds after we hear the dead man joyously sing, we drop back into the “present” hear his friend suffer a break down on 'Mellow My Mind', closing out one of the strangest three song sets on any album. A desperate bluesy mouth harp leans into to slow jagged chords, and then Neil releases one of the most desperate pleas for help ever put to tape…

I’ve been down the road, and I’ve come back.

Lonesome whistle on the railroad track.

Ain’t got nothing on those feelings I had.

Baby mellow my mind, make me feel like a schoolboy on good times.

It’s a song about wanting to retreat into the safety of youth, far away from the horrors around him. If for some perverse reason you don’t have time to listen to the whole album, jump to 0:56 on track 6 for a twenty-second summation. As Neil’s voice rises higher and higher you can hear him lose it. He sings, or rather tries to sing the word “track.” It’s out of tune, and out of hope, broken wide open and was thankfully never rerecorded or autotuned.

A third tragedy, a double murder in a bad drug deal in Topanga Canyon, Neil’s neighbourhood, is the subject of the heart wrenching 'Tired Eyes'. Neil talks through the verses before sliding into a sad pretty melody repeating, “Please take my advice, open up those tired eyes” on the chorus. It’s a tender song stripped of any bravado about the confusion of death and fragility of life. Critic Richard Meltzer once described it as “if Dylan did Wild Horses.”

The album then closes with a heavier and even sloppier version of the opening track, the tinkling piano now replaced with a growling blues guitar that sounds like a gorilla kick-starting a Harley.

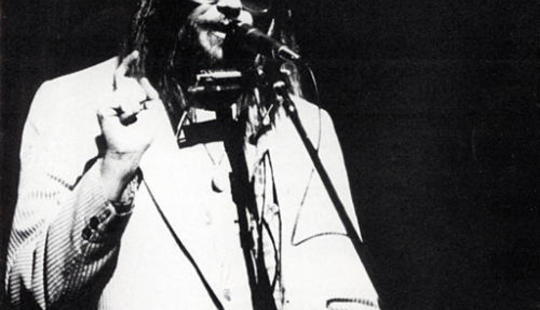

The ominous album cover is mostly black, and features an obscure and menacing monochromatic shot of Neil on stage in a Seersucker suit, wearing a harmonica and strange smile. This same cover art adorned the t-shirt that Lynyrd Skynyrd’s Ronnie Van Zant was allegedly buried in.

One of many oddities about the album sleeve (including an unexplained photo of Roy Orbison) is a report by a Dutch journalist who visited the sessions, printed in full, in Dutch. Neil claimed that he was so gone at the time that it might as well stay in the foreign text; it was all Dutch to him. It translates as follows,

“Most of Neil's songs about Danny's death reflect his guilt complex. Neil seemed to fall back into an even deeper depression. Then he began drinking, became sentimental and generally intolerable for anyone who had anything to do with him. It's said that those around him treated him with great caution for fear of provoking him, causing him to retreat and become a recluse.”

The more studio production that goes into a record, the more dated it becomes. Some albums, like Purple Rain or even Kid A, apparently aspire to be pinned to their time through digitized effects and overdubs. But elsewhere these studio tricks make some albums hard to listen to years later. So the raw nature of Tonight’s The Night, like a lot of Dylan or early Stones, lends it a timelessness that makes it still sound alive and present today.

While the album is hard going in places, it is apparently nothing on an the original sprawling mix, complete with between song drunken raps, that Warner Bros refused to release, and has yet to see the light of day despite the pleas of fans. Neil’s dad Scott once heard this version and described it,

“It is a handful. It is unrelenting. There is no relief in it at all. It does not release you for one second. It's like some guy having you by the throat from the first note, and all the way to the end.”

Of course Tonight’s The Night didn’t sell as many records as Harvest, but like Woody Allen’s dark follow-up to Annie Hall, Interiors, the album was maybe a necessary outlet granted by the record company to move the artist on, up and out of a heavy funk.

To claim that albums of this candour no longer exist would be wrong, and retrophillic, but just the fact that a major label released this messy document of a man in such a fraught state is something that may never happened again. These kinds of albums are seemingly only released these days as anthological bootlegs after an artist has died.

Some have given this dark masterpiece a more universal meaning, even calling it a calculated concept documenting the downfall of the hippie dream - a set of saturnine songs to parallel the murder at Altamont and the end of the 60s.

David Marsh wrote in The Rolling Stone, “The demise of counterculture idealism, and a generation's long, slow trickle down the drain through drugs, violence, and twisted sexuality. This is Young's only conceptually cohesive record, and it's a great one,”

For me it is not a picture of a dislocated generation, but a dislocated man going through an exorcism of grief, while drinking in LA. Forty years ago in a temporary studio in instrument rental warehouse on Santa Monica Boulevard Neil forced himself to sing about this pent up stuff in order to get it out and move on. This culminated in a seedy, ragged and brilliant record, a personal document of a man in chaos and distress. So personal that Neil felt the need to apologize in the final liner note –

"I'm sorry. You don't know these people. This means nothing to you."