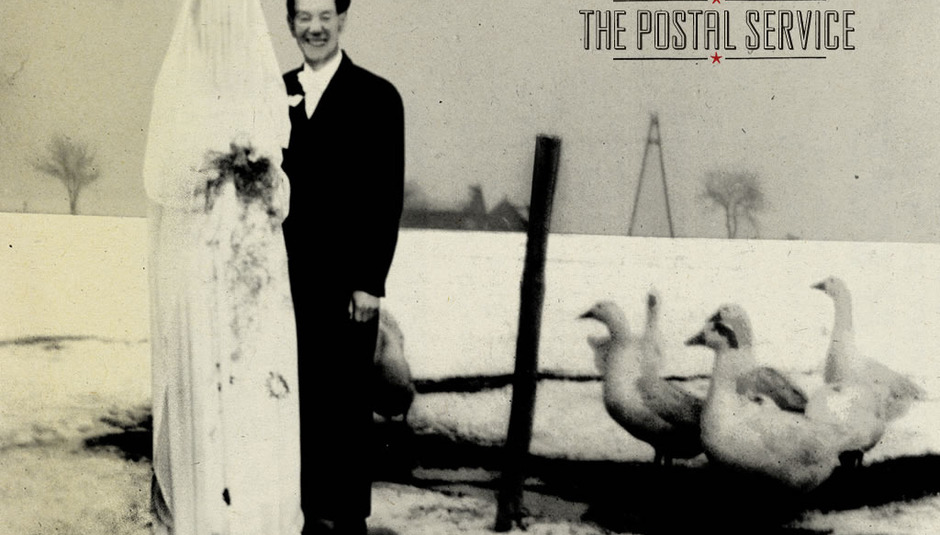

Between the message boards and editorial arm of DiS, we’ve always felt discussion of new records should be presented as just that - a discussion. Our humble boss-on-high Sean Adams once described the site as "an aggregator of individual opinions", and it’s in this spirit that we introduce a new feature: two writers, with two clashing opinions on one canonical record. As tends to be the case here, neither represents a DiS 'party line' - these are the voices of two fervently passive-aggresive fanatics, shouting into the abyss to their hearts’ content. Maybe it’s a move towards total subjective transparency in music reviews, or maybe for you this all falls under the same cynical umbrella. Probably you’re thinking, ’I don’t care, stop talking to me. I have a family and a cat to feed’. That too is totally understandable. In any case, here’s the first installment, which examines Sub Pop’s 10th anniversary reissue of The Postal Service’s landmark debut, Give Up.

Why Give Up Shouldn’t Have Bothered, by Jazz Monroe - 4/10

There’s something lamely seductive about the notion of discrediting an underdog success a few years after its commercial canonisation. Still, even before becoming Sub Pop’s most lucrative release since Nirvana’s Bleach, Give Up was already ensuring the delivery of lavish contempt to The Postal Service’s doorstep.

Admittedly it’s tough to argue. There’s the patronising quirk, the tenderised whine, the smug self actualisation narrative. The lyrics. The second verse of ‘Clark Gable’. The narcissism. The inverse narcissism. The way Ben Gibbard’s compassion is invariably bastardised and redirected inwardly. The lazy submersion into fantasy, and this compounded by the preclusion of self-diagnosis within the lyrics, ie. what the dude needs isn’t any packageable life lesson but some kind of dignity biopsy. The way ‘Nothing Better’ ham-fistedly approaches self-awareness - “You’re getting carried away feeling sorry for yourself,” coos Jenny Lewis - but is so simple-minded and unpunctual as to repel sympathy. The presumption that listeners will credit a hyper-sensitive, financially secure 27-year-old whose lyrics illustrate a moral and philosophical universe the size of a chip shop car park: “I watch the patchwork farms / Slow fade into the ocean’s arms / And from here they can’t see me stare / The stale taste of recycled air / Baa ba-ba-ba, Baa ba-ba-ba”. All that kind of shit.

Some questions: Why is this popular? Who mythologises it? How do they make a living? You might roll eyes, but why dance to an indie totem so limp, weedy and above all immature? The immaturity of Give Up is boundless, encompassing its ideals, responses, virtues. Like the dimmest rock’n’roll, it’s myopia masquerading as inspirational platitudes. Arguably all this is pretty much harmless. Thing is, by repeatedly burdening us with his total awareness of his romantic folly, Gibbard evades detection of something much more pertinent, namely that he’s hooked on adolescence - and worse, he glamourises it, fetishises the concept of flaccid self-analysis as a way of life. Give Up, suffice to say, is a terrifically ill-conceived thing.

However - and I acknowledge your dwindling enthusiasm for the review’s ironically needy and arrogant imperial phase, I do - Gibbard and Dntel’s pinpoint execution of all this is, occasionally, a sort of poignant listen. For starters, setting aside issues of tone and content, Gibbard - in much the same way Meg White functioned as Jack’s yin - is probably the only singer you’d suit to the duo. Forgetting the moral complacency, forgetting the half-arsed lyrical payoffs, Give Up asks questions about your taste that only a record so beautifully wrought, so end-of-level accomplished (at least within its tiny world) could effectively ask. Despite its personality crisis it’s an album you’re loathe to truly despise, like a clumsy goalkeeper, or a family dog that shat on the stairs.

And perhaps this, after all, is its finest achievement.

There are some bonus tracks as well. From a fan perspective the pair of new ones almost vindicate the whole hagiography, despite operating precisely within the expected parameters. Though profoundly tepid in a spiritual sense, they’re pretty and neat, in a bonus track kind of way.

One question is why somebody’s tacked five remixes onto an album that was notably an electronic-indie synthesis to begin with. Among reworks like DJ Downfall’s vaguely banging ‘The District Sleeps Alone Tonight’ there’s nothing really resembling an answer, but the marbly Give Up-era discards make serviceable b-sides and, although it has a definite favours-for-mates vibe, the Shins’ acoustic ‘We Will Become Silhouettes’ at least transfigures Gibbard’s lyrics into an accessory of Jimmy Mercer’s princely larynx.

Overall, I mean, you see the appeal: it’s cosy stereotype-confirmation, cushioned by a pleasing abundance of textural variation in the music. As did mid-career Cure, the Postal Service express little beyond the modernness of their spiritual vacancy, and that’s alright (albeit an increasingly institutionalised go-to excuse in music). So yeah, if you like novel things and love the Postal Service - go ahead! - buy this record. But do so preferably on the proviso that you already possess some semblance of emotional stability and an arsenal of blues and/or soul and/or hip-hop, ie. music of real-world strife, man. Synthetic white boy blues - that’s about the size of it, really.

Give Up: A Persistently Modern Classic, Sybil Schreiber - 9/10

For decades, defensive critics have been showing off their reactionary muscles by picking on plaintive, introspective male artists. Don’t be fooled: these missives are, invariably, coming-of-age parades representing triumph over the review writer’s inner-adolescent.

I’ll start by acknowledging a simple fact: anybody carrying around so much hate for a band like The Postal Service is probably a really big arsehole. People who demand the middle-class purge their art of self-centredness, whininess. Well, excuse me as I sell The Bell Jar, Radiohead’s discography and most every album covered in Our Band Could Be Your Life. Self-expression is positive and essential. Mine is as valuable as yours. Get used to it.

If any record released in 2003 deserves a reissue, it’s Give Up. That’s because it’s the most effective collection of melancholy anthems since The Replacements’ Let It Be. The reissue’s two discs comprise a fizzy mix of all the enduring classics. Also some subtle remixes, covers by the Shins and Iron & Wine and a couple of new tunes - namely ‘Turn Around’ and ‘A Tattered Line of String’, two buoyant jingles as sweetly innocent and addictive as they come. Bound together, Dntel and Gibbard are presumably incapable of making a bad song. Old B-side ‘There’s Never Enough Time’ knits up a warm sonic blanket as Gibbard mumbles angsty asides into his pillow, while the Styrofoam remix of ‘Nothing Better’ takes that pillow, puffs it up and lays down your head while kissing you on the cheek, all woozy whistles and ventilated summery synths.

Throughout, ’50s movie-style strings weave neatly between romance, wist and despair, never over-reaching. The beats are borderline Europop, and the lyrics have an abstract virtuosity that’s often overlooked. Suffice to say this is far from a single-purpose emo pop record. Sometimes I go to Give Up for comfort, less often for nostalgia. Either way, when I put on the Postal Service (or write a review of the Postal Service) I’m not expecting bloody Shellac.

There’s a deeper problem here. We should spread the word: it honestly isn’t such a massive sin to be frank about, like, having emotions. On a daily basis people go weepier and wallowier than Gibbard does on songs like ‘Be Still My Heart’ and ‘Nothing Better’. During hungover chats, Facebook convos. You know the type. This is an emotionally vulnerable man, sure, but one writing simple, honest, catchy indie songs. On ‘Such Great Heights’ Gibbard has penned a universal love song that could’ve spawned from no generation but his own. His integrity surpasses that of any scene-spotting buzz band with a cloud formation name. Yet that stuff passes with scarcely a raised eyebrow - now what’s that about? It’s like folk have issues with the presence of honesty among less-than-macho boys. Or at least would rather they kept it to themselves. As if the dismissal of albums like Give Up is some kind of preventative measure against sentimentality, immaturity and, er, non-masculinity in males. Seriously? What are these people hiding? How large are their cars?

Ultimately when it comes to ripping into the Postal Service the white-male-privilege argument is redundant, because beyond the insular world of privileged music fans this discussion doesn’t even subsist. (Want a good example of Synthetic White Boy Blues? Try your entire review, dude.) This is the kind of music that changes people, often positively, whatever their age or social circumstances. What’s more, if we can’t respect the magical, non-prescriptive nature of taste, then we’re in the wrong game as music writers. Simple as. 10 years on, Give Up remains an entirely modern classic.