In a 2003 promo interview, Will Oldham explained his multi-moniker approach as a way to ‘allow both audience and performer a relationship with the performer that is valid and unbreakable.’

Okay. I’m sure there are some diehard Oldham/“Prince”/Palace fans out there who’ll take exception to this, but I don’t give a shit. I agree that the performer-audience and performer-self relationships are complex, and I understand the desire to differentiate one project from another. But — and I’m sure nobody knows it better than Oldham himself — the only thing that really makes a lick of difference is the songs.

Fortunately, Oldham is a very good songwriter. His monikers may complicate your Spotify browsing, but they won’t impede your listening experience. I can forgive a little compulsive shapeshifting as long as the content is good.

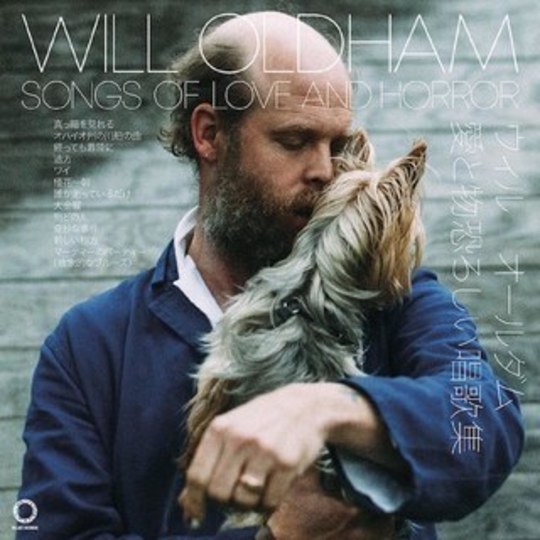

His latest album, Songs of Love and Horror, is, essentially, a career retrospective. In the music industry’s more robust days, you might have called it a ‘greatest hits’ collection (do they still even make those?), and by opening with a stripped-down ‘I See A Darkness’, it sets itself up as such. Of course, he had no choice but to open with that song; Johnny Cash didn’t cover just anything, you know.

Tradition is important to Oldham. The album title throws back to Leonard Cohen’s Songs of Love and Hate (1971), a maniacally distraught early-career effort. Oldham, too, trades on articulate despair. He goes particularly Cohen-esque on ‘So Far And Here We Are’, a minor-key brood concluding with the straightforward, “I once had a partner but now that is done”.

The sentence is written at about a second grade reading level. This is something Oldham does: he’ll gather visceral momentum around some very strange phraseology, and then release it with Avett-level unaffectedness. Simmer, if you will, in this section of ‘Wai’: "The way our shelter moves above, controlled by just my hand, in short, the death you’re dreaming of, the drowning down of man".

I don’t really know what he means, but I like it. He sings these lines with a medieval lilt, a melody which touches three discrete modal territories, and caps the eventual refrain with, “I found the hard way, love is true”. It’s as if he — and, resultantly, listeners — have to puzzle through acrobatic diction to earn a simple turn of optimism.

Oldham is eccentric. In his case, ‘eccentric’ means ‘simultaneously reverent and irreverent’. Eccentricity seems to go without saying, especially in an indie genre where technical proficiency is, at best, optional. The Daniel Johnston mode of ham-fisted guitar work and psychosis-saturated vocals is industry standard for ‘authentic’.

Had he stalled at ‘Party With Marty’, delirious album closer and Jimmy Buffett pastiche, Oldham’s eccentricity might well have categorised him as one more sub-earnest singer/songwriter more committed to idiosyncrasy than quality. But he didn’t. He got to ‘The Way,’, which is everything Fleet Foxes wishes it could be.

I have to spend another few sentences on ‘Party With Marty’. Ten of the other 11 songs are hi-fi, tender renderings of canonical Bonnie “Prince” Billy songs, plus one well-executed a capella cover of Richard and Linda Thompson’s ‘Strange Affair’. ‘Party With Marty’ sounds like it was recorded on cassette when Oldham was 19, lonesome and dreaming of beaches. His voice is higher, his pitch and guitar work are shabbier, and of course the production quality is — well, absent. The song is sort of amusing; two lonely dudes find salvation partying with two surfer girls in “bikini tops and cutoff jeans”. It’s a little long, and his idiosyncrasies haven’t yet crystallizsed into pure strengths, but Oldham’s idea, I think, is to demonstrate how far he’s come, giving a little wink to his proto-self in the process.

I like that he takes songs from 1998-2016 (who knows when ‘Party With Marty’ comes from), I like that they’re all delivered by just Oldham+guitar, and I even like that the moniker he chooses is his actual name. It makes it feel more straight-faced, like finally, after all these years, he’s willing to look his audience in the eye.

Though, the brilliance does start to fade around the two-thirds mark, such a test of an album. I don’t know whether it’s us, if people are just programmed to get a little bored of one artist after 30 minutes, but two-thirds always seems like the point of no return. It’s a little bit of both here. ‘Big Friday’, track #8 and the first one to do relatively little for me, is an ode to happy love, love in bloom. The faux-nineteenth-century lyrical turns which, earlier, ring so fresh, begin to feel a little stale:

You saved me from melting, baby You saved me from stinging and being holed up From breaking in snow and killing, more Overspilling my runneth cup

It’s a little clumsy. ‘Most People’, too, is a loose link, overindulging in Oldham’s trademark murk. Its midway shift from 4/4 minor to 3/4 major is a little contrived, and the associative lyrics further numb the listener to the song’s virtue. Even his ebullient high register can’t quite resuscitate it.

But, good God, this man can sing. His devotion to eccentricity can make you forget. You can never be totally sure what’s accidental and what’s not, but taken to their most naked essences, these songs put Oldham’s chops on full display. He comes through. Listen to the chorus of ‘The Way’, how his voice is literally the mist on the mountain, the space between black branches.

Half one is lovely folk, half two is slightly less even, slightly more idiosyncratic folk. Whatever you do, stick around for ‘Party With Marty’. I can’t authoritatively say he recorded it as a kid, but, come on. If you also love the Beach Boys and might be an irredeemable solipsist, this guy’s for you.

-

7Dustin Lowman's Score