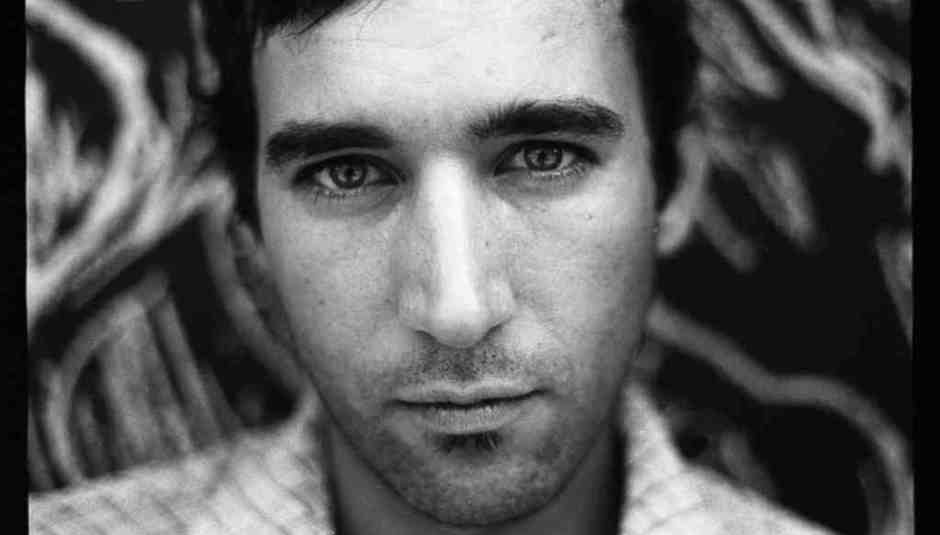

It is 9am Eastern Standard Time when DiS calls Sufjan Stevens at home in Brooklyn and he is wide awake and affable, even as a temperamental connection – and me getting myself into a tizz as I stumble over my question about the humongous finale of his new album – threaten to derail proceedings.

The Age of Adz is out next week was released yesterday, and an audacious, brilliant record it is too. It is also likely to be a divisive one, wherein he almost entirely abandons the template of 2005’s star-making Illinois in favour of the kind of glitchy electronica and synth first explored way back in 2001 on Enjoy Your Rabbit (a song-cycle based around the animals of the Chinese Zodiac).

The last-minute, primitive nature of the album, outsider art, personal dysfunction and psychobabble, experimenting with the long form, Woody Allen films – and what’s wrong with civilisation – are some of the things touched on below. Like the new LP: it’s a long one.

DiS: Are you excited about releasing The Age of Adz?

Sufjan Stevens: Yeah… I’m excited. I’m always more excited by the process than the product, so the album itself is exciting because it’s the conclusion of a work, like giving birth, and an album release is sort of like a christening of a child, and everybody comes and looks at it, and oohs and aahs and makes their judgements. But the process itself, just to get to this point, was pretty unusual and pretty exciting. Pretty weird.

DiS: How did it all came together? It seems like up until quite recently you weren’t sure what you were going to release, and then suddenly the EP and the album were announced really quickly.

SS: Well, the EP and the album were both done at the same time. The EP was stuff that I felt proud of, but didn’t really fit on the album. But the album itself… it really came together last minute. I had been working on material that was more long form – like, there’s several songs that were the length of ‘Impossible Soul’, but they just weren’t coming together. Then I had this other material that was the result of experimenting with electronics and drum machines and synthesisers, and one day I just had this revelation that that was the album. It became really clear to me that it wasn’t about any kind of big concept; it wasn’t about masterminding any kind of long form, epic vision. It was really just about these concise pop songs that are experimenting with the drum machine and synthesiser. I put everything else away and decided to finish that stuff.

DiS: A while ago, not long after The Avalanche I think, you spoke of how you were getting bored of banjos, trumpets and things.

SS: Yeah.

DiS: I guess that still stands?

SS: Yeah, I mean – I think this material is the result of a concerted effort to undermine or sabotage the usual tools that I use for songwriting. Obviously I’d gotten tired of the banjo and the guitar and the piano, and I’d gotten tired of my voice. I thought I’d kind of… outgrown all these peripheral elements – acoustic elements and orchestral elements – and I wanted to just focus on sound experimentation. And so I started working more with synthesisers. There’s a kind of organic nature to the synthesiser that’s different to anything that can be created by a human being. I don’t know; in some ways I feel like the record is kind of rebelling against the human element, and really focusing on sound, you know – as the main event. Or, the sound synthesis as the main event.

DiS: …I remember you saying of The BQE last year that you felt liberated by the inherently less human nature of it all.

SS: I think that a lot of my other albums are very personal, but they’re not… instinctual, necessarily. There’s a refinement that characterises a lot of my other stuff. And there’s something about this new stuff to me that just seems really propulsive, and experimentally explicit: speaking very concisely, and with basic language. I’m allowing myself to do away with the all the figurative trappings. I just wanted it to be more explicit.

DiS: You’ve mentioned how it arose out of this initial desire to engage with the long form – it seems like you’re always attracted to these big, grand projects. Even way back – like when you were writing songs assembly-line style in college, and one of the songs was, even then, 17 minutes long.

SS: Yeah (laughs).

DiS: Why do you think it is, that you’re so compelled by these big, vast ideas?

SS: I’m starting to question that impulse, you know? The desire to tackle vast, conceptual landscapes. I’m not sure why I work that way. It might have to do with being at school, and kind of being conditioned in writing class, or in literature classes, to go for the really conceptual approach, where you design the pieces, support the pieces with evidence and arguments, and then draw it all together. I think that’s just how you’re conditioned at school; to think very broadly and pick out specific things and introduce them, subject by subject and paragraph by paragraph. Maybe it’s from that. I don’t know.

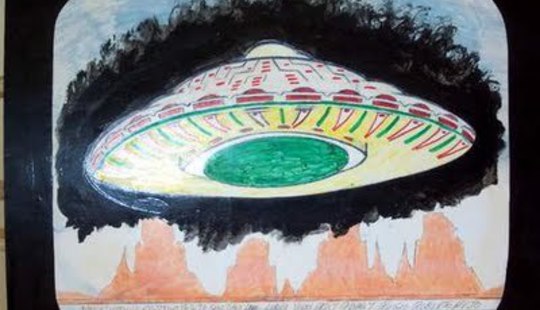

DiS: How did you become interested in Royal Robertson and his work?

SS: A friend of mine made a documentary about Royal Robertson and some other artists – American outsider artists – and he had asked me to record some music for the film, and then to add inspiration he showed me some of Royal’s work. I started scrutinising the drawings and I noticed there was text all over them, so I started transcribing some of the text, and I think that that stayed with me, for a long time; some of it started to come up in the lyrics, in the songs I was writing.

He was really into astrology, technology; fascinated by UFOs. And he would also draw these pastel scenes of a man and a woman making love, or in a romantic embrace. He was obsessed with the apocalypse and the end of the world – he saw himself as a prophet, and… I don’t know, I guess the more that I studied his work, the more I felt a weird affinity to this guy and the story of his life. His weird imagination and the dysfunction within his family and how he felt about society… his oppression, regards wanting love, and his inability to really function in a way that could accommodate that. Obviously there’s a very deep, inherent sickness within him, and his work, and I don’t… I’m not going to pretend that I have a mental illness or anything like that. But I think as an artist you’re forced to reconcile with your own dysfunction, and how that dysfunction motivates your work.

DiS: The idea of human connection, and what it’s possible to achieve, seems to run deep throughout the album – on the title track, for example, which is both foreboding and filled with a sense of wonder at the same time. And there’s that lyric: “When I die, I’ll rot / But when I live, I’ll give it all I’ve got.”

SS: I’m really in touch with mortality, and I think that I’ve probably meditated on that issue too much. But I think that there’s something very galvanising about that meditation, because it allows you to – you know, it can be debilitating – but it also can allow you to really enjoy each moment you have. Every breath. And we don’t really recognise that, ‘cause we’re so busy. I think that for all of my obsession with the end of the world, or the Apocalypse, or whatever kind of foreboding tragedy I can conjure (laughs), the moment is now: you’re here, today, living and breathing, and we should really be joyful about that, and I think that that’s impossible, for me, to really fully embrace that.

DiS: The album is predominantly written in the first person, with you addressing yourself at certain points – perhaps most explicitly on ‘Vesuvius’ – which explores some pretty dark themes, but also comes off like a bit of a pep talk…

SS: There’s a kind of solipsistic, insular dialogue going on in some of these songs. It’s a little bit self-centred; a little bit disparaging, but also meant to encourage myself out of a state of mind, a despairing state of mind. I don’t necessarily think that that makes for great art, but I think that it was important for me to showcase this kind of process, of confrontation with my own, resentful disorders. My emotions.

DiS: In some interviews last year you expressed a kind of frustration with music in general, and the notion and meaning of a song. Were you surprised at how widely that got picked up?

SS: Obviously a lot of that got a bit out of proportion. It’s not as if I was having a creative crisis or an existential crisis in which I debilitated. But at the same time I wanted to really question the form, and the fundamentals of my work – the song and the album, and I would question my voice, and what is the function of music in society. It’s important to be mindful of meaning, of one’s work, but I think sometimes I get carried away, and I start analysing or scrutinising something to the point that it no longer has meaning. I figured that was kind of unhealthy, so I worked myself out of that.

I think a lot of this album is representing that kind of process. There’s a logic that runs through the songs, where I have a problem, a disorder, or some kind of obstacle, and I lyrically work through it. Some of it’s pretty crude. It engages with some very personal psychobabble. But it was important to work through.

DiS: ‘Impossible Soul’, for example, traverses all these different places – from calm to questioning to triumphant… before reverting to… a really quite beautiful close. It sounds a bit like a plea for unity, as well as an admission that we can’t expect everything to go well all the time. Does that sound right…?

SS: It’s like a Woody Allen film, you know, where there’s the slapstick on the surface that everyone can appreciate, but then, deeper, there’s all these original details. Maybe at the heart of a good Woody Allen film there’s some kind of universal tragedy of humanity that he’s speaking about; a much bigger thing. ‘Impossible Soul’ is really about a very primitive object. I want to get with a girl, and there’s all these obstacles, and shortcomings, and miscommunication… and this is a basic fundamental of life, between two human beings.

But then very quickly – through an expository detour – it becomes something else. It’s all about personal happiness, or the state of mankind, or the cosmos – the cosmos is drawn into it. And then it becomes about… what is at the heart of our inability to really connect? Is it fear, or is it self-consciousness? And then it becomes a kind of therapeutic discourse that becomes the centrepiece of the song. But it’s no longer about, just like, “girl, I want to get with you.” It’s more like… what’s wrong with civilisation (laughs).

DiS: Also, it’s kind of interesting how the album opens with ‘Futile Devices’ – certainly the least electronic song here – with the end of ‘Impossible Soul’ bringing it almost full circle. Was that intentional?

SS: I think so. I think that maybe for some listeners this record is maybe too much – too much electronics, too much glitch – I wanted to remind people that there’s a humanity beneath all this. The underlying theme here is pretty basic. It’s about pleasure, it’s about touch, it’s about affection, and that’s something that first of all is very human. In spite of all the bombastic sound collage, the elements are actually relatively simple.

DiS: Do you find it hard to finish things?

SS: This was probably the most arduous process for me. Making this album was more arduous than anything else, because there was so much confusion, and there wasn’t any clarity to the process. It all came together pretty last-minute, and it was a bit slapdash. Originally the EP and the full-length were one big long thing, like one long record, and it wasn’t until the eleventh hour that I was able to draw a distinction between the two. I think that’s an indication of a real shift in the concept. I wasn’t working with any goals, there wasn’t an objective; I was just writing and recording and because of that I had a real lack of clarity and direction. Somehow – I don’t know how – it all came together at the end. It’s beyond me how that happened.

DiS: I read an interview with Jonathan Franzen recently, someone who’s obviously also attracted to large-scale projects, and he said something about how after every time he’s completed a novel he feels like he’s completely forgotten how to even begin the process of writing the next one. Can you empathise with that at all?

SS: Well, after The BQE I felt a real lack of any grounding; I lost my bearings. And like I said I actually think that this record is a real response to all of that, and after this record I feel much better about embarking on something new. It’s allowing me to reconcile with starting over. But I understand that phenomenon – there’s a kind of post-traumatic stress syndrome that happens after I make an album: it’s like exhaling all the oxygen and all the life out of you, then feeling like there’s none left to breathe in. But I don’t feel like that now – I feel much more optimistic right now.

The Age of Adz is out now via Asthmatic Kitty

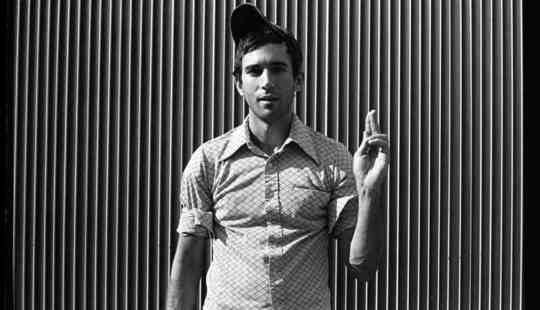

Photos by Marzuki Stevens, UFO by Royal Robertson