When my brother and I were total band geeks, we LOVED Emerson, Lake and Palmer. Somehow he obtained this greatest hits collection, and we listened to it in his car on the mornings that he drove me to school. We shared lots of music this way, and Ben always knew more about it than me –

like Dizzy Gilespie: 'you notice how the quality gets better here? And the songs get longer? That’s because the recording techniques got better' -

and Gustav Holst: 'no, Lee, don’t touch the volume – you keep it at one level, so the piano parts sound soft and the fortissimo parts sound loud. Like they’re supposed to. See?' -

and his favourite obsession, Steely Dan: 'This sax solo was actually meant for a electric guitarist, but the guy never showed up. So they found this guy instead, and he nailed it in one take.' (Do you know which song I’m referring to? I don’t remember.)

But one morning, we both heard 'Pirates' for the first time, and neither of us said anything. The orchestra builds, the ship embarks from the harbour, the sun climbs over the wooded horizon, the highway stretches before us. And Ben turned to me, and I turned to him, and we just stared dumbfounded at each other.

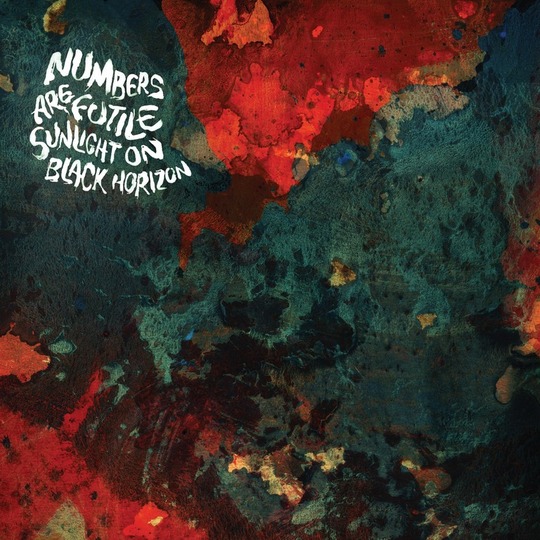

I relate all this, because Numbers are Futile remind me of that feeling, that unabashed wonder, the spellbinding magnificence unbridled by self-defacing irony or vapid guitar wankery.

There are many facets to the duo’s magicks. A shade of the Mediterranean swirls within like ink blots in the ocean, exotic strings lacing stately synth melodies and pummeling percussion. Opener 'The Great Chimera' evokes the gilded halls of King Crimson, darkened by marching soldiers; 'We Float' coats the theatrics of Yes with an obsidian sheen; 'The Threat' blazes forward like the Emerson, Lake, and Palmer tracks that captivated my brother and me, but in much less time and with much more impenetrable enigma. Progressive, maybe – but Numbers are Futile don’t waste precious minutes on orchestral movements or long-winding jams. It’s a very post-punk sort of urgency.

Otherworldly experiences clash with ultra-modern angst. Between the dancing fiddle that graces 'Monster' and the trippy tribal incantation (in Greek?) within “In The Fields”, lies the thundering and ultra-modern 'Oblivion Days'. No time to waste, no time to die, they say, and you believe them – the celestial, Cluster reverie of the intro gives way to a relentless battery of drums, shoving us awake into the cold, cruel sunlight with ominous synths and piercing, shoegaze-y wails.

Numbers are Futile have clearly achieved that rare mind-altering power that we often dub 'psychedelic', without banking on handy signposts like wah pedals or drug references. Indeed, anyone who enjoys the leisurely shuffle of more conventional prog groups like Yes might feel shut out by the duo’s impenetrable lyrics and laser-honed pace. Songs like 'Vice Over Reason' don’t invite you to zone out or drift off – they crash down like the tides of the sea, rolling ever forward, dragging you under and spitting you out again on the rocky shore. Only on the regal 'Doomsday Blues' does the duo finally settle into a cathedral-esque lull, but even then the second half builds steam to a dynamic finish, as if the triumphant horseback hero of a film learns of a new crisis in the closing scene and thus gallops rather than ambles toward the setting sun.

Y’know, at some point, I thought I’d say that Numbers are Futile were dreamers, detached from the material world, but multiple listens to Sunlight On a Black Horizon tell me that’s not true. They’re architects – Bauhaus architects, who firmly believed that form should serve function in any design, be that a house, an ergonomic folding chair, or the pieces of a chess set. Numbers are Futile play as if they, too, have their own aesthetic manifesto to uphold.

(Geez. Now I just wish I could share this with my brother and knock HIM out with MY wisdom.)

-

8Lee Adcock's Score