If the interview she recently gave to The Guardian is anything to go by, Lana Del Rey’s capacity for the sharp division of opinion remains as keen as ever. The piece painted a deeply unhappy picture of her life post-‘Video Games’; it opens with her drawing unsettling comparisons between herself and two of the 27 Club’s most prominent members, and proclaiming that she often wishes she’d already joined their ranks (assuming she’s still with us past next Saturday - her twenty-eighth birthday - she’ll have avoided doing so).

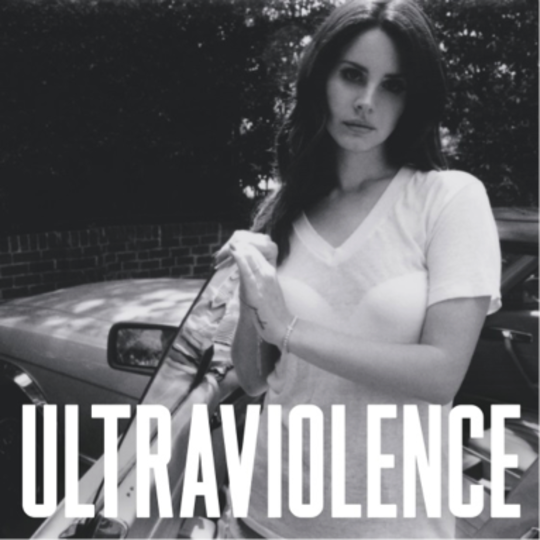

Whether or not this latest episode in a decidedly turbulent relationship with the media is indicative of somebody in a genuinely unhealthy psychological place, or simply the near-tasteless rumblings of an entertainer with a vested interest in presenting themselves as intriguingly as possible, is something that will doubtless be pored over in microscopic detail elsewhere. As, for that matter, will pretty much everything other than the music on third album Ultraviolence: irrespective of whether Del Rey is the hyper-stylised product of an industry obsessed with aesthetics or just an artist with a keen sense of the bigger picture, it was disarming to receive an unadorned stream of a record (late last week, with paranoia over leaks having apparently reached fever pitch) from a artist with such a penchant for extravagant presentation.

And then, you hit play, and realise why so much of the extraneous matter surrounding Del Rey focuses on a sense of drama. Her music positively drips with it. ‘Cruel World’, in opening the record, quickly has you realising why criticism of Del Rey’s vocal ability is largely redundant; her performances don’t need wide melodic range, or even straightforward emotional depth, as long as she’s able to keep up the sheer breadth of theatrics demonstrated on Ultraviolence. She veers between vulnerability and menace with a conviction largely missing from Born to Die, and then runs with it. She brings a tension to the title track that belies its glacial pacing. The vocal on ‘Fucked My Way Up to the Top’, especially, is so much more multi-faceted than the snark of the title suggests; it’s a tentative, almost whispered turn that spins aching sadness out of empathy where you’d expect coldness and detachment to prevail.

That Del Rey’s performances are so consistently convincing is crucial to Ultraviolence’s appeal, because it’s really the only thematic area in which she hits far more than she misses. The record’s narrative is at best muddled and at worst, open to accusations of style over substance; I’m sure that the tales she weaves are supposed to be deliberately vague, but they’re so repetitive - shadowy stories of doomed relationships - that they begin to grate fairly quickly, and the album’s weak lyricism leaves it with little to fall back on; ‘Sad Girl’ and ‘Pretty When You Cry’, in particular, feel like close retreads of Born to Die’s brand of glamorous sadness - lightweight references to infidelity, drugs and heartbreak all present and correct. Put simply, Ultraviolence is difficult to genuinely engage with on an emotional level; sure, Del Rey sounds as if she means it, but really listen to what she’s singing and you have to wonder if she actually knows what it is that she’s meaning.

The truth, though, is that ‘Video Games’ wasn’t so explosively popular because it gave ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ a run for its poetic money; it was a runaway success because it sounded fantastic, and so does Ultraviolence. Dan Auerbach of The Black Keys seemed like a bizarre, even worrying, choice to produce the record, especially given that he’d be arriving off the back of the blindingly gaudy El Camino, but he has done a stellar job of making this surely the most sonically irresistible pop record of the year. The temptation to let Del Rey’s obsession with the cinematic run away with her must have been strong, but instead, this is largely an exercise in subtle beauty, in calculation and restraint.

It’s actually pretty minimal: whilst it would have been easy to throw the kitchen sink at Ultraviolence, there’s no real sense of bombast, with the instrumentation largely used for colour and punctuation. ‘Money Power Glory’ is a case in point; a rudimentary drumbeat and the intermittent squeal of a washed-out guitar allow one of the record’s standout vocal turns to take centre stage. On the record’s highlight, ‘Old Money’, the strings flutter in and out as Del Rey offers up a heart-wrenching take on ageing - “will you still love me when I shine / from words but not from beauty?” A sparse piano aside, it’s the only backing she needs to deliver the closest thing Ultraviolence has to a “Video Games”.

And then, she closes on a cover of a track made famous by Nina Simone, a move that requires a frankly cartoonish degree of either bravery or stupidity. To her credit, it almost works. By rounding things off with ‘The Other Woman’, a track drenched in monochrome Los Angeles glamour from a bygone era, she’s nodding and winking; she was aiming for film-noir atmospherics after all. It’s just that, with the record so often lyrically indistinguishable from Born to Die, she hasn’t exhibited its subject matter in a way that’s particularly gripping, or even, at points, coherent. As an album to invest in, feel sentimental about, or be genuinely thrilled by, Ultraviolence falls short. Take it simply as a sumptuously-presented pop record, though, and you have to wonder if you’ll hear a better one this year.

-

7Joe Goggins's Score

-

1User Score