Kid A is the corner-stone of Radiohead’s career, the brick holding up their 90s and noughties personas and connecting the two to make a whole. For me, it is the record that transformed a band I liked to a band I love and a gateway to new sounds for me to pursue.

It’s an intrinsically personal record for me. As the new decade kicked in I was starting university, starting to indulge in electronica as well as experimental genres like krautrock, and was politicising myself (I was reading Naomi Kline’s No Logo, as Kid A was released). In the post-Britpop era and living in uni halls crammed with the sounds of UK garage and gleaming, soulless pop, Kid A was the record I needed at that moment.

Personal elements aside, this was also a time of transition for Radiohead, the result of a band struggling with its own identity and dealing with the pressure of universal critical acclaim and to deliver another OK Computer. Speculation mounted that this follow-up would bring ‘rock’ back to the masses catapulting them into the enormo-dome leagues of Pink Floyd, U2 and REM. Instead what emerged was an unexpected aural tangent from a band leaving their stadium rock potential behind to tread a more, experimental, esoteric path.

It was late night during the early throes of uni-life that strange Stanley Donwood adverts started appearing on late night TV, accompanied by snippets from what we could only assume were new Radiohead tunes. There was no explanation, but these were the promotional ‘Blips’ for Kid A. The excitement built.

This was an age when mythology could still be built around a record release, and the band did few interviews and next to no other promotion leading till its 22nd October release, crafting a marketing void that both increased hype and side-stepped expectations. The album was all that mattered. Because of this the first listen was an ‘event’, a communal gathering, and it not only changed my view of Radiohead but also what I wanted from music from that moment on.

Lyrically, the cryptic, paranoid end-of-the-world narrative fed into my personal deep-delve into radical politics and ideas and in many ways soundtracked a friendship with a conspiracy theorist who believed in the Illuminati, faked moon landings, and an alien race controlling us. Kid A seeped into every crevice of my life as I was forging who I would be and was working out the world. For anyone who hadn’t heard these songs take shape live in 1999 and 2000, especially at their epic ‘Big Top’ gigs in London’s Victoria Park, and even to some extent those who had, these final recorded versions were everything we’d been waiting for.

Sure, as many snobby scribes would state, Kid A was not a wholly ground-breaking or unique record, wearing its influences on its sleeve with honour, but few bands have so wilfully and successful shed their skin to emerge as a different prospect as Radiohead did here. This was the birth of the real cult of Radiohead and the strange dichotomy where a band too-big-to-fail could also be outsiders. It is this idea that has fascinated me ever since.

In the same breath, you had “fans” (and some critics) bemoaning the lack of guitars and the step away from their stadium anthems, and also journalists attacking them for mining the ideas of other artists and simply not being experimental enough. But as a middle finger to both camps Kid A provides both elements of the past and of their shining future which would yield their best work by far. Far from not being experimental enough, the album happily sat in a personal playlist where I was discovering albums like Can’s Tago Mago, Autechre’s Incunabula and Godspeed You! Black Emperor’s F♯ A♯ ∞. This is where I place Kid A and why it rekindled my love for a band that I was losing interest in.

In many ways, I consider follow-up Amnesiac to be the better album, as the band broke even further from the past, harnessing a wider range of ideas including delving much deeper into jazz territory. But in a way, this makes Kid A even more special. With all tracks from both records coming from the same sessions, it is clear that Kid A was crafted as a stepping-stone, the gateway to a new dimension where the possibilities are endless.

In guitar ‘anthem’ ‘Optimistic’ and the subtle, floating emotion of ‘How To Disappear Completely’, they provide tracks that could have sat on The Bends or OK Computer with ease, but don’t at all feel out of place on Kid A. It’s a statement of “We can still do this stuff, but we’re so much more.” Radiohead are daring you to come with them on a new journey.

Elsewhere, the concept of what Radiohead was considered to be pre-2000 is completely lost, in particular Thom Yorke’s voice – something so integral to their previous success. Amid chimes and cascading jazz rhythms his voice is processed into a unrecognisable robotic tone on ‘Kid A’ and dropped completely on the ambient wave of ‘Treefingers’.

The run of opener ‘Everything In Its Right Place’, with its machine manipulated voices and lulling simplicity, ‘Kid A’, and stand-out track ‘The National Anthem’ is still, today, one of the boldest choices for three opening tracks of all time. It is easy to imagine this was the moment when ageing rock-journos were scratching their heads perplexed. ‘Idioteque’ proved that these electronic dabblings could yield best-in-genre type results; it’s Radiohead in full dancefloor-filling bombast mode whilst losing none of their experimental ambitions.

So much – positive and negative – has been written in the history, makeup and creation of these tunes read our 2009 re-appraisal for that, but I always, after clicking play, fall into the camp of considering this a landmark record.

Kid A is not an album that can simply be discussed in isolation. It laid out what it could be to be a big band in the new millennium and how bands could create their own rules. There’s no argument that Radiohead were in the privileged position to do things other bands could not (after years of major label support), but activity such as live webcast when the internet was barely a thing, the online Blip campaign, and the eventual ‘pay-what-you-like’ price on In Rainbows highlights a group how consider the rules to be there to be broken.

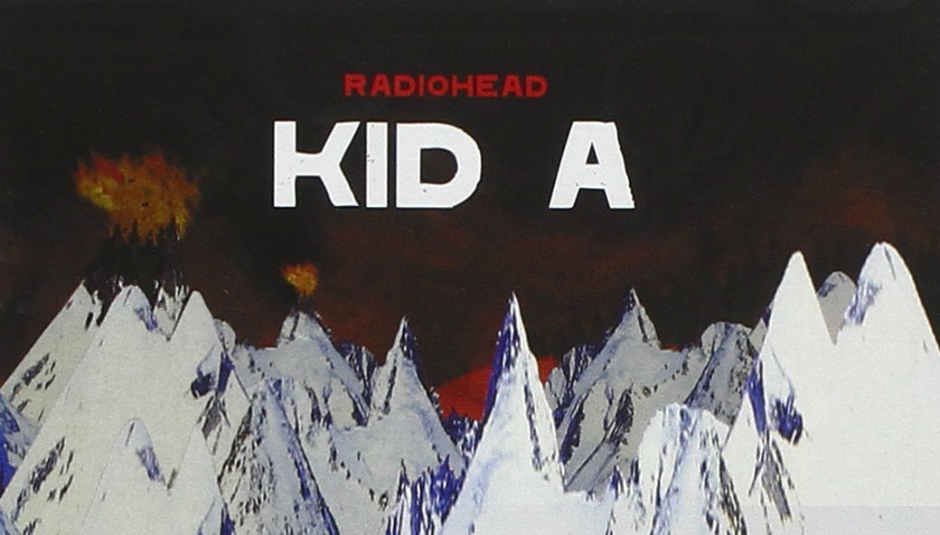

On the CD package, the liner booklet contained nothing but strange artwork and no notes. Kid A was intended to be listened to, and not poured over as to how they had created this new sound. Discovering the hidden booklet under the plastic CD shelf full of cryptic riddles and surreal art added another dimension to a complete experience of an album.

The lead up to the release of Kid A created a mythology, and was the last real ‘event’ release before file-sharing and piracy took hold. And this immersive relationship continued well after the first play of the album. The full package was soon completed by ‘Pyramid Song’ coming as a single, Amnesiac, and the June 2001 Jools Holland mind-blowing special broadcast as they proved to the nation they were now untouchable in the live arena – every idea had come together. That July, we all headed to South Park in Oxford for the massive homecoming all-dayer, with support from Sigur Ros, Supergrass and Beck, to witness a special moment when Radiohead acknowledged their roots by showing how much they had grown.

The over-weight, grumpy ‘fan’ loudly stating: “I hope they don’t play any of the new shit” as they started to play simply cemented that Radiohead were no longer his band, or really anyone’s band – they were what they wanted to be.

This work is so much more than just an album for me; it’s a key piece in the puzzle of my life as I transitioned into the next era, almost mirroring the bands itself. Washed in personal nostalgia and the entire experience of its release, its importance can’t be understated. Aside from the sentimentality, Kid A is an album that stands up as an all-time classic. A brave move that brought leftfield ideas into mainstream conversation in a way that was accessible to many, and totally confusing for many people who deserved to be confused.