Love for Grandaddy, and the band’s commander-in-chief Jason Lytle, runs deep. We’re standing outside Rotterdam’s Schouwburg theatre complex after the band’s set at the Motel Mozaique festival. The mood is one of tired professionalism – only two dates remain on this leg of their European tour – and a few of the band and crew avail themselves of the opportunity to smoke as they watch the last of their gear being brought downstairs and packed into the van. Lytle, stoically sipping a beer, is particularly subdued; he wasn’t happy with either the crowd or the sound. “Festivals, man,” he sighs wearily after coming off stage. “After three songs, I was like: ‘OK, it’s gonna be one of those shows…’” But he’s approached by a portly older gentleman whom I recognise from the front row; he danced and moshed and punched the air for virtually every minute of the hour-long set, singing along to everything, even the new material. Would he mind signing a few records, the man asks? No problem replies Lytle. A sharpie is procured before the man produces two large boxes containing just about every single and 7” the band ever released. Lytle nods, smiles, and gets started; the man looks like he’s about to burst with happiness.

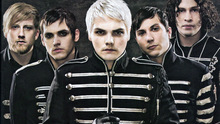

While the acclaim and respect afforded the band over the last twenty years is easy to understand, the fact they are here at all, and appear relatively unscathed by their roller coaster ride, isn’t. Grandaddy – Lytle, Kevin Garcia, Aaron Burtch, Jim Fairchild, and Tim Dryden – always seemed unlikely heroes, their slacker, lo-fi indie ethos sitting uneasily alongside fame. At the height of their powers they released The Sophtware Slump, a modern American masterpiece and an album that perfectly captured the post-millennial comedown before it happened. David Bowie promptly anointed them as “my new favourite band”, and they toured the world several times over, appearing on countless TV shows and radio programs along the way. But as their star rose, behind the scenes things were falling apart; the pressures of touring, and the demands made of them by their newfound status took their toll, and the band imploded in 2006. So burnt out was Lytle that he fled his hometown of Modesto, California to live in Montana’s sprawling wilderness, literally in the middle of nowhere. He even called one of his solo albums Dept. Of Disappearance.

Their first “comeback”, in 2012, was rapturously received; re-issued vinyl and t-shirts sold out almost instantly, and a short tour – culminating in a glorious, emotional two-hour show at the Shepherd’s Bush Empire – demonstrated just how much they’d been missed. The day after the Empire show, Lytle told me “I know a lot of it is just nostalgia” but he seemed intrigued and resigned in equal measure regarding the inevitable clamour for new material, and a proper return. “I’m looking forward to hearing another Grandaddy record, not the actual making of it…[but] I think it’s gonna happen, yeah” he concluded. But as the months turned into years, the lack of news was increasingly received by fans with a resigned shrug; things die, life goes on, and Grandaddy were simply fulfilling their own prophecy. So it came as a pleasant surprise when last summer new music, an album, and a tour were all announced; they were back as a fully-fledged band.

“I was comfortable with it creeping up on me,” Lytle says by way of explanation. “There are so many concerns and baggage that goes along with it, I needed to really feel like it was something worth doing.” He claims there was never any epiphany or formal band meeting where they decided to take the plunge, simply “a slow accumulation of songs and music that started to sound like Grandaddy.” If that sounds somewhat tortuous, that’s because it was; prone to self-doubt, Lytle wrestled with the dilemma that new material couldn’t just be snuck out, to stand on its own. There’d be shows, travelling, and conversations with people like me. “If I was going to open that can of worms, it was going to take its toll in other ways. So I had to be really certain that it was a good idea to embark upon this, you know?”

We’re talking via Skype the week before Last Place is released, and while he’s in a jovial mood, he already has one eye on what he calls “the shit-storm on the horizon.” Grandaddy always struggled with the outside pressures being a successful band brings and Lytle, as the main songwriter and primus inter pares, was affected more than most. He talks about feeling “too close” to Grandaddy in the past, and going round and round in his own head trying to get some critical distance. “My perspective was just not one that would allow me to view it innocently, or even clearly,” he says, and dealing with their past success, and the burnout it led to, clearly still plays on his mind. He’s wary about being on the road again, but says the band are now grounded enough to deal with it, having learned from past mistakes.

“The pace and the scheduling is a lot smarter now, but there are some realistic things which are just obvious; no more hard alcohol, no more drugs. Drinking is fine, though; I gravitate towards red wine, it keeps me in this kind of perfect fog.” He partly blames his obsessive, competitive nature, something he developed during his teenage years as a skateboard prodigy. “I grew up kinda competitive, a sponsored skateboarder, travelling and hanging out with all these psychotic friends; drugs, fighting, partying, heavy metal, and punk rock. I’ve kind of gotten used to a life of high intensity, but then I’m also someone who really requires a lot of alone time; it’s a powder keg for a guy like me, being in this situation. When people say: ‘Let’s add on high-pressure shows every night, in confined spaces, with all the weird tour energy,’ of course things are going to go haywire every now and again.”

Sounds like they’re constantly walking along the razors edge I say. Is it such a struggle not to topple off? “Well, there is no real blueprint for how to do this,” he says. “But I’ve learned a lot, and the band have really calmed down as well. It’s not like we are old and boring; we still talk shit and have drinks, tell jokes, and have a lot of fun, but at some point, if you don’t have the sense to mellow a lot of those sharp edges then it’s just your own fault.”

For a lot of bands who resurface after an indefinite hiatus, tension and long-held grudges simmer away under the surface of their public cordiality, but Grandaddy appear remarkably sanguine after years of struggle. Lytle is on record about how much he tried to protect the others from fame’s pernicious glare, and how he ensured that their first reunion, in 2012, was as much about the band, and everyone getting a fair share, as it was anything else. Polite to a fault, they seem genuinely enthused about their second wind, joking and joshing around on stage and having a great time; in short, truly happy. Lytle agrees.

“Backstage we’re super relaxed, laughing, and everyone is normal. It’s pretty exceptionally comfortable, to be honest; there are no weird issues, no freaky egos or strange dramas. But I’ve said this a few times; it’s strange to think that if I hadn’t shut it down when I did then there’s a very good chance we wouldn’t be at this fortuitous point in the band, or even doing this at all with our friendships intact, a little bit more wisdom. I’m not taking credit for that; it’s just funny how things work out sometimes.”

Indeed it is. It’s also somewhat ironic that having moved back to Modesto, and coming to terms with his place in the world and his relationship to the band – and to music in general – something else was falling apart; his marriage. Unsurprisingly, pain and sadness found their way into the songs he was writing – quiet moments of grief such deleting photos from your phone and packing up shared belongings are raked over and dissected – but he’s also quick to point out that he never wallowed in self-pity, or used it as an artistic crutch.

“I mean, if the worst I have to do is complain about a crumbled, dissolved relationship of ten plus years…there are a lot of people who have it way, way worse on every realm of the scale. It was just years and years of trying to slog this thing out and have it somehow fit in, and then all of a sudden just going: ‘Alright, that’s it!’” He’s not bitter, and nor was it acrimonious; more of a conscious uncoupling. “I’m actually still really good friends [with her]; it was just like putting your hands up in the air, shake hands, back out and then walk away. But that’s life, and it’s just getting through that stuff. As many times as we’ve heard it, and as corny as it sounds, you do for the most part come out a little bit stronger and a little bit wiser the other end.”

This acceptance of fate, and the way things are, is central to Lytle’s beliefs and the music he makes. It’s the resigned shrug of Generation X, a “whatever, man” writ large, or as he puts it: “just all the little things living and dying around you, and all the connections that you make. It can be something like the passing of the seasons and a tree losing its leaves, or just the geese heading south. It’s all around us; some people are just a little more affected or honed in on the details.” He’s never done therapy, but wonders if maybe he should; his approach to dealing with mental issues has simply been to immerse himself in work. Quiet periods of introspection – his “Here comes the feelings!” moments – are problematic, the mental space an excuse for negativity to take over. “So I will go out for a drink or three; then I’ll hop on a bike and get into the outdoors and find some way to beat myself up and either stay numb or keep myself distracted.”

He’s been coy in the past about the extent to which his lyrics explore his own feelings and emotions; a common theory is that Jed The Robot, the sad humanoid that’s central to The Sophtware Slump and whose “son” appears on Last Place, is somewhat autobiographical, and gives Lytle the chance to be open in a way he can’t – or won’t – in the first person. “You know it’s all a metaphor / For being drunk and on the floor” he sings on ‘Jed The 4th’, an interesting little aside considering some of his past excesses. “I speak the truth, and I’ve been there many times,” is all he’ll say when pushed, but he’s more forthcoming about directness and the level of honesty he’s now able to achieve in his writing.

“The two solo albums that I did were a nice opportunity for me to whine in solitude a little bit more comfortably. Then there’s that thing too where I have got to keep it true, keep it real, in order for the songs to mean a lot to me, and for me to just go full on invested in them. They have to be fuelled by all this emotion of mine. But I’ve found myself being consciously aware of wanting it to be a little bit more enigmatic, mysterious, or Grandaddy-like, and not so much like this one solo character that’s just like whining publicly.”

Grandaddy have always written sad songs, but they’ve never lapsed into angst or despair. Last Place has plenty of frailty and moments where Lytle sounds genuinely crushed, but it’s also shot through with defiant optimism and built around several moments of pure joy. It sounds like he’s in a happier place. “I am definitely on the upswing. I think there is something in my DNA that feels like a failure for giving up but that is just something that time will heal. Maybe, as the scenery of one part of your life transitions into the scenery of another part of your life, these things take care of themselves.”

I’ve often heard artists temper the catharsis of public soul-baring with a neat analogy; that up on stage, night after night, you’re picking the scab off the wound, exposing it, and never letting it heal properly. He likens songwriting to writing a journal – “the whole point of it is to get it out of your system” – but admits that the repetition of performance, when it comes to some songs, can be unhealthy. “That’s the double-edged sword of writing something that means so much to you and is so tied in with these personal memories. It allows you to sing it with conviction and it gives it a longer shelf life, but it does a number on your brain though too. It doesn’t quite allow you to move on as quickly as a normal person would.”

But he’s coping with the pressure, and his emotions, far better than before. A little positive mental thinking – he claims he writes mantras and sticks them all over his house, a particular favourite being “Good thoughts, good actions, good day!” – has gone a long way, as has figuring out what really makes him happy, and what he needs to do away from the band, and away from music, to maintain a healthy balance.

“I really thrive when I’m far way from people, either in the mountains, hiking in the desert, or just areas where there is just nobody else and I can just kind of wrap my head around things at my own pace. That’s where I’m happiest, and the rest of it I just navigate through and try to get through it as unscathed as possible. I’m a pretty responsible person – I have a great credit score, and keep up with my personal affairs – but sometimes it all becomes just a bit too much. I’m happy when things are simple, and I am like a naïve kid who looks at things and wonders.”

One part of touring that he’s genuinely enthused about is the love and admiration they receive from fans of the band young and old. He’s excited about playing the Roundhouse – just about their biggest gig ever – and doing festival season with some proper gear, performing to “all the people who caught us on a bad night, never saw us at all, or came around to the Grandaddy thing late.” He likens preparation for all this to a climbing expedition, and says that his skateboarding past, and the competitive nature of it, means he “thrives on getting to that moment and pulling it off.”

Few bands inspire such devotion in their 25th year, something Lytle does not take lightly. “I would be an evil ingrate if I didn’t admit how important all that love and support has been. It really helped fuel me a lot through the album making process, as a matter of fact. I get these big waves of self-doubt and insecurity, continually asking myself: ‘Are you sure this is a good idea?’ But the enthusiasm and the relentlessness of a lot of the fans has just been amazing and not totally expected either; the appreciation they’ve shown has played such a huge part in whatever this phase is.”

I ask what phase he thinks it is. I’d debated with several friends and colleagues whether this was a new beginning, or a valedictory last hurrah; turns out it’s somewhere in between. Grandaddy will be back he says, but the end is very much in sight.

"I don’t want to do this for that long. I actually have my own timeline set up right now. I’m 48 right now and with all this travel and spending all this time indoors…there ‘s too much of it. It’s kind of like shoving a square peg into a round hole for me, and I need to spend not as much time around people, and not as much time in the public eye. I plan on getting out around 50, and that gives me enough time to do something else… We did a deal for two albums, so I’m definitely going to make another record.”

As Grandaddy, or as Jason Lytle?

“Another Grandaddy album. As a matter of fact, I was out on a run two days ago, and part of my brain was already thinking about what kind of songs would be on there. I was like: ‘No, no, no. Stop these thoughts, it’s too soon!’ But I couldn’t stop them; I’m a bit of a planner like that. And I started getting this idea of a late checkout. You know when you check into a hotel and the first concern the next morning is what time you check out, and can we extend it? I almost feel like this Grandaddy thing is almost like a late check out thing.”

“So, I was thinking: ‘How can you say goodbye and also admit that you’ve stayed around a little bit longer than you should have?’ I started riffing on this idea, and then it just went away. So definitely another record, and if everything goes as planned then I will get the fuck out of here by the time I’m 50.”

Clearly, it won’t be easy to just abandon music, something that has defined his life for nearly quarter of a century. He says he’ll always dabble – “I’ll always have some remote little recording set up, like a piano and an acoustic guitar” – but that, for his own sanity, the wider role of music and the band being a career needs to end.

“It can’t just go on forever. I mean, it’s super amazing that we have been afforded this opportunity and it’s mind-blowing that I am even here talking about this again and that there is still so much enthusiasm, but I have this other life I want to live, and it has a lot to do with being outdoors and not being around hoards of people, or even small groups of people. I want my body to still be able to carry me up mountains and across deserts and do long distances on my bike. If I’m going to orchestrate any kind of reinvention at all, then it’s not going to have anything to do with music – I’ll start hand-crafting machetes or drive an ice cream truck or something – but I don’t really want to do this forever.”

Back in Rotterdam, gear packed up, the band are drifting off. There are a few loose ends they need to tie up, so we agree to meet in their hotel lobby for one last drink. By the time I get there, Lytle has headed to bed; only drummer Aaron Burtch and their affable soundman Jerry remain. We share some wine and chat about life on the road, and the strange position they find themselves in. It will be a sad day when they finally call it quits, when Jed the Robot is powered down for good. I think back to how Lytle described the writing process – “years of working on this fucking thing” – and how difficult he found it. “At every stage there was so much love, care and concern guiding it; I was protecting it the whole way through. But it wasn’t until the mastering stage, when I got to listen to everything lined up, how the segways were happening, songs going from one to the next…finally, that was my first little moment of relief. I really felt like I did something good. That was the first time I was able to share that moment with myself, and I was comfortable with the fact that this is what people were going to hear.”

That the fruits of his artistic struggles speak directly to so many says so much. As a fan, one always wants more; losing Grandaddy the first time was painful enough, and knowing what’s coming, we can but enjoy them while they last. For Lytle, perhaps for the first time, the path is clear; the accidental star who yearns for the quiet life, yet remains determined to go out on a high, on his – and the band’s – own terms. The American hero returning to the warm embrace of nature and solitude, happy to wander around the great outdoors, is a fittingly Grandaddy way to bow out. Lytle has his second calling, and while he’s not done yet, it’s one he intends to answer while he still has the chance.

This article was written before the tragic and untimely death of bassist Kevin Garcia earlier this year. Our thoughts remain with his friends, family, and all who knew him. The band have set up a GoFundMe page to help his family with the coming expenses. Please give generously.

Last Place is out now via 30th Century Records. Read our 10/10 review for the album here. For more information about the band, please visit their official website.