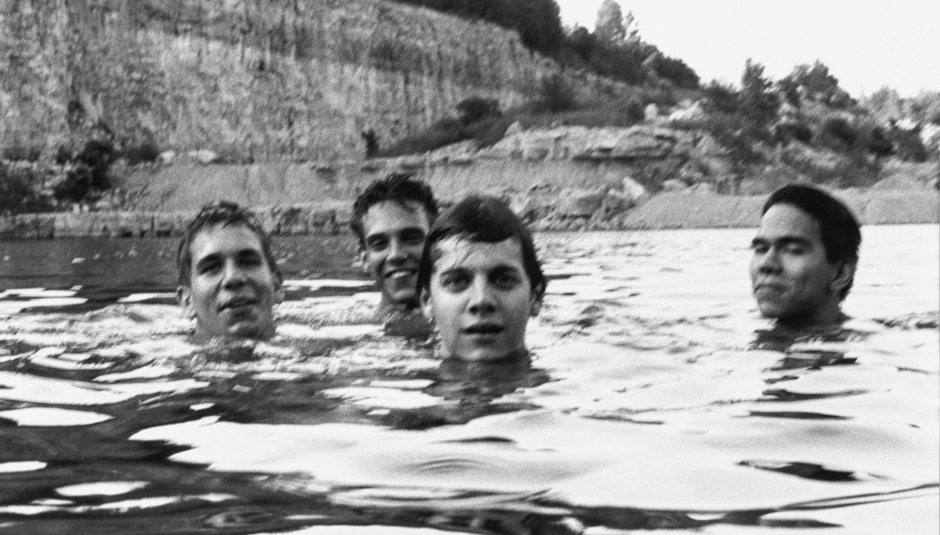

Next month, Touch & Go records are releasing a new box set of alt-rock pioneers Slint’s second album Spiderland. The set includes a version of the album remastered by Bob Weston, previously unheard recordings, a 104-page coffee table book with foreword by Will Oldham, and Lance Bangs’ long-awaited documentary on the band, Breadcrumb Trail. In the first of a two-part feature, DiS spoke Brian McMahan and Britt Walford about the years of obscurity in which Slint made a seminal album and split up before it was even released.

Read Part Two of the interview here: "I'm trying to find my way home: DiS meet Slint (Part Two)

As you’ll know if you read any Lou Reed obituary back in October, Brian Eno once said: “The first Velvet Underground album only sold 10,000 copies, but everyone who bought it formed a band”. The members of Slint were barely teenagers when this claim was made in 1982, but the same principle applies to their alternative rock masterpiece too.

There’s another quote that’s handy to have in the back of your mind when thinking about Slint’s iconic, gorgeously creepy and uniquely unblemished second album Spiderland. This one comes courtesy of punk rock gob-on-a-stick Ian MacKaye:

“The people of Louisville are just fucking crazy, right. They’re just insane.”

There were a lot of great punk bands in Louisville, Kentucky, in the ‘80s. As far as Slint goes, it starts somewhere around the time when local pre-teens Britt Walford and Brian McMahan were in one called Languid And Flaccid. Lance Bangs’ new documentary, Breadcrumb Trail, can help you fill in the gaps but eventually, after stints in Squirrel Bait and Maurice, Walford and McMahan hooked up with bassist Ethan Buckler and guitarist David Pajo, and before you know it you’ve got Slint.

Bangs’ film (which is finally being released as part of a bumper-sized, remastered reissue of Spiderland) does two things very well. It debunks much of the mythology that’s always surrounded Slint – more of which later – but in doing so, creates a whole other mystery. How did four punks who spent more time tuning up than playing live; whose first public performance was during a church service; whose other gigs no one went to anyway; who made ‘anal breathing’ tapes of each other farting; who recorded a game-changing 40 minutes of chillingly enigmatic spoken word vocals, weirdly lingering repetitive riffs, awkwardly nuanced beauty and ferocious bursts of emotion, only to split up before it was released – how did these guys end up being in one of the most distinctive, influential and inspiring bands of all time?

“I think we knew that we were doing some things that maybe were a little different, but I think really we were just doing it to please ourselves, just for the fun of it,” explains vocalist and guitarist McMahan. “It wasn’t a big shock when people were like, ‘Okay, you guys are really boring’. We did not have anyone beating down our door trying to get us to play.”

Certainly, one of the early highlights of Breadcrumb Trail is some particularly uncomfortable high school battle of the bands footage of Slint playing the bizarre ‘Nan Ding’. Even if you’ve witnessed the reverential atmosphere at any of their recent shows, you can still imagine being in the audience at one of those gigs in the mid-eighties and wondering whether these guys are complete idiots or just nuts. Turns out they were ground-breaking, so was innovation high on the agenda at the time?

“Man, I really don’t think so,” says drummer Walford. “For better or for worse I think we were really in our own world. I definitely was [laughs].

“I thought that the sound of the band kind of organically grew – well, it definitely did – from our instruments and the kind of things that we were into and our sensibilities. I thought that that was unique and really cool. I liked that a lot. As far as the actual music, I didn’t really think about it.”

Between school, browsing pet stores and playing practical jokes, Slint managed to write and record their first album Tweez. Engineered by Steve Albini, it was released in 1989 by their friend Jennifer Hartman to little fanfare. With its souped-up distortion, maddening changes of pace and extensive inventory of unexplained clatters, it’s one of those classically flawed albums – very enjoyable, and full of ideas for sure, but the sound of a band that’s still got its best tricks up its sleeve.

“I think that the writing on Tweez and the craft is pretty remarkable for a bunch of 16-year-olds,” is McMahan’s take on it, and it’s hard to disagree.

“Britt’s fingerprints are all over the Tweez stuff,” he adds. “If you want to consider a sort of creative unifying, driving force behind both records, you’re going to have to reconcile that with Britt.”

Although he’s a little shy and hesitant on the phone, it’s clear from the plethora of anecdotes that shape Breadcrumb Trail that Walford is as much an eccentric prankster as a creative genius. It was his idea to name all the songs on Tweez after the bands’ parents because he “thought it would be funny”, and he never laughs more than when Lance Bangs asks him if there’s the sound of someone taking a shit hidden somewhere in the mix of the album. (He doesn’t deny it.)

Not that this means Tweez should be read as a bunch of teenagers goofing around – even at 17, Walford’s eyes were on a career as a touring/recording artist. “I’ve always thought about it that way,” he says. “I’ve never taken anything like that not seriously, personally. I think that generally, at least, the other guys feel the same way. I’d have to let them speak for themselves, but all I ever did throughout all of my growing up was play really, so I was always really, really serious about it.”

Buckler, meanwhile, was serious enough to quit the band when Tweez was completed, dissatisfied with Albini’s contribution to the album’s sound. He was replaced by Todd Brashear and Slint went on their first and only short tour, pissing off countless motorists in the locality with the goofy handwritten signs they stuck in the windows of their van: we are small weak men who are SCARED of lesbians, WE’RE IN A BAND AND WE’RE CUTE… you get the idea.

The next stop for Slint was college, with each band member choosing a different Midwest institution save for Walford and McMahan, who both went to Northwestern University in Illinois. All four musicians continued working on new material, with Walford more than anyone, it seems, laying the foundations for the Spiderland sound, even if he was stuck behind a drum kit onstage.

“Even if it was collaborative, the driving force to a big extent – that would be Britt,” says McMahan. “The fact that he ended up playing drums, that’s sort of in my mind maybe a happy accident. He’s an amazing drummer but he’s a really gifted musician. He’s a trained pianist. He’s very expressive on whatever instrument he has in front of him. Him becoming known as a drummer really had as much to do with him having parents that were cool with him having a drum set in his basement.”

As you’d hope, Walford himself is far more modest about his role in Slint: “Man, that’s… I don’t know… I definitely like, just make up music all the time. The other guys, each of them, were just so integral as well, creatively. I feel like it’s a four-way thing.”

When they all returned home from college in the summer of 1990, the songs that would form Spiderland really began to take shape in Walford’s parents’ basement. Pajo’s burgeoning love of the Minutemen gave him a taste for clean guitar sounds and, as McMahan, explains, “Even though there are those taut, explosive aspects of the songs or the sound, we were coming from a pretty quiet minimalist phase when we wrote the material on Spiderland.”

And this, really, is where the mythology of Slint – the rumours of mental illness, fallings out and reclusiveness – begins, and where it is expertly unravelled in Breadcrumb Trail. So spoiler alert, if you’d rather see this stuff through Lance Bangs’ lens first.

One event you’d expect to have cast a shadow over the making of Spiderland is when McMahan was hit by a car and nearly killed as Slint were preparing to record, but as far he’s concerned it’s not worth reading too much into.

“It was a pretty weird event but I don’t think it really impacted my interest in the music,” he says, adding: “It could have been a lot worse! It was a wake-up call a little bit but to be honest I still don’t think I had, even after that accident, a real good grasp on mortality. I was still 20, 21. It was just kind of surreal to me and that was about the extent of it.”

The real pressure surrounding Spiderland stems, it seems, from the fact that Slint only had one weekend to record it in. This was felt by some more than others. For Walford’s part, he “didn’t feel rushed at all. It was just kind of, you know, like any recording session I guess. When they turn on the tape machine you’re just like, ‘Okay, here goes’. Other than that it didn’t feel unduly pressured.”

But it was different for McMahan: “I don’t think it stopped being fun because we were really excited to do it. I think we were all anxious, for sure, and I may have been the most anxious out of us. That really just stemmed from me being perfectionistic and really wanting to control the sounds and the quality of the performances, and how it came across. We got lucky basically, because we had very little time to do it. It was fortunate for us that it turned out how it did.

“At this point there is very little, if anything, I would change about it. At the time, oh man. I would have taken months making that record if it had been a possibility.”

One of the most intriguing legends of the Spiderland session is the one in which McMahan is physically sick from the exertion of screaming “I MISS YOU” at the pivotal climax of ‘Good Morning, Captain’. He doesn’t remember, so this may be a case of the myth telling a better story than the reality. “I’ll say that we were all pretty much spent,” he recalls. “I remember sleeping on the floor of the control room and waking up kind of in a daze. That’s about all I remember.”

What is clarified in Breadcrumb Trail is that McMahan checked himself into a hospital shortly after recording Spiderland. This is never expanded on, either in the film or during our phone call.

McMahan left the band before Spiderland was released, and the others decided they did not want to continue without him, despite their impending European tour commitments. His reasons, as with so many artists struggling to make music and make a living, were financial:

“I felt really, really like we had a good chemistry and it was a lot to draw on with those guys. Especially because we were so close, there was a real sense of responsibility on my part. After Spiderland had been released there was some critical praise and we were really thankful for that – it did not translate into record sales. For me, deciding to quit was me knowing that I needed to make a living and I didn’t think I could divide my time between the band to do it the way I wanted to do it, and also make sure I could pay rent.”

If there’s one thing that unites all of the events from the days of Languid And Flaccid to the release of Spiderland in 1991, it’s that each one makes it less and less likely that Spiderland should have ended up in anyone’s record collection. But it did, and really, there’s only one explanation for how an album so strange, complex and obscure could have ended up changing the lives of so many music fans: the people of Louisville are just fucking crazy.

Read Part Two of the interview here: "I'm trying to find my way home: DiS meet Slint (Part Two) where we look at Slint’s rise to acclaim in their absence, and how they were finally able to reap the rewards of Spiderland.

The Spiderland box set is released on Touch & Go Records on April 15th.