As OutKast’s Aquemini turns 15 this week, Champion Sound explores the legacy of the duo’s boundary-breaking rap classic.

--

Three years before Aquemini became the first southern rap album to recieve The Source’s hallowed five mic rating, Madison Square Garden teeters on the brink of chaos. It’s the magazine’s 1995 awards show, and the rap industry is crammed into the Paramount Theatre as the victory parade for Biggie’s Ready to Die rolls through. Led by Puffy, Bad Boy wears black as a uniform, while Death Row performs their own medley decked out in matching oversized denim. These days rap beef is played out in 140 characters – all caps – but back in ’95, warfare between the two labels is being brewed under the glitzy pretence of awards show legitimacy.

If east vs. west had been the ceremony’s front page headline, OutKast are the southern side show collecting an award to a smattering of boos. This is the climate in which the group’s career begins – even as they’re honoured as best new rap group, their humble hometown shout outs are unwelcome to the crowd of rowdy New Yorkers. A minor incident at the time, but by now it resonates as strongly as anything from that night – from Biggie’s towering performance and stalking of the stage, to the sinister Cali funk of ‘Keep Their Heads Ringing’. Neither Andre nor Big Boi quite find the words to respond to the hostility, yet in the heat of the moment Dre utters a parting shot that now reads like a prophecy, simply – “The south got somethin’ to say.” A retreating plea for respect is all it is, but that gut reaction would soon evolve into a hardened, artistic statement that would change rap forever.

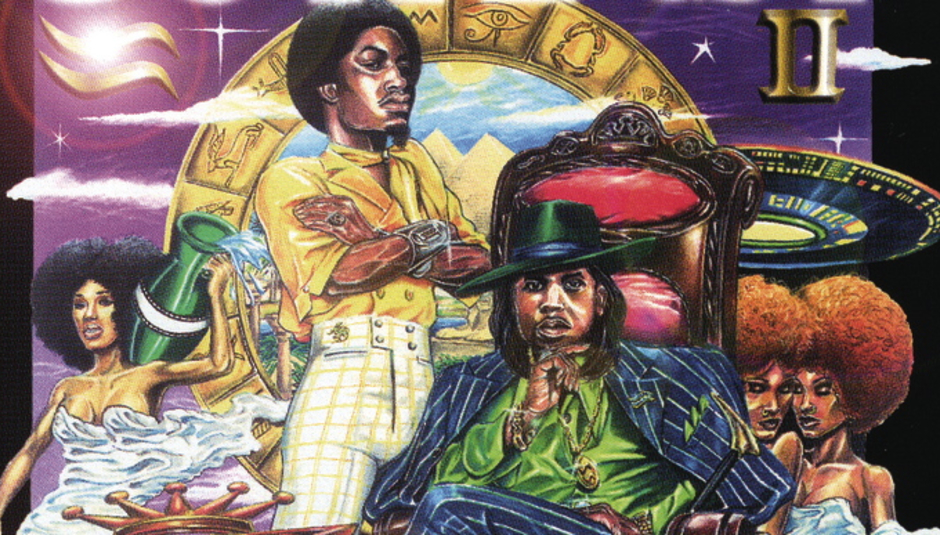

Aquarius (Big Boi) and Gemini (Andre 3000) align in the video for ‘Rosa Parks’, as their already contrasting characters are accentuated to new extremes. Big Boi, for whom a costume change constitutes throwing on a different sports jersey, naturally comes out fighting with a call back to ATLiens - still finding time to leave his knuckle print on your eye. He talks a rough game and his style is direct as ever, yet the group’s soulful future funk lends playfulness to his rugged wordplay. That’s not to say he isn’t capable of landing a sucker punchline, but when he does it’s designed as a catalyst to dance rather than brawl.

Andre, by this point, exists in a world of one. His attire in the ‘Rosa Parks’ video consists of a military helmet, NFL shoulder pads over an otherwise naked torso, and a pair of pants made out of brightly coloured feathers. Despite appearances, this is no random assortment of wardrobe leftovers. Dre’s upper body armour is symbolic of his frustrated mind-set, deflecting questions over his sexuality and drug habits – despite being both sober and straight – but keeping things cartoonishly flamboyant from the waist down. It’s 1998 and a fitted T-shirt is enough to label a rapper ‘soft’, but Andre is out here wearing feathers as he leads a marching band to a harmonica interlude. He fires back at haters on Aquemini’s first song proper, ‘Return of the ‘G’’, creating a series of detestable gangsta scenarios which serve to emasculate his detractors as brainless thugs unable to support a family. Before Kanye, Drake, Danny Brown and Lil B – Andre was opening the doors so that anybody can walk through them and rap.

Even ignoring the subjects he and Big Boi tackle, when the different timbres and pitches of their voices cross paths they fulfil all that you could want in an emcee. The interplay is flawless; Big Boi’s dizzying but highly rhythmic rhyme structures are the perfect balance for Andre’s higher register and existential flights of fancy. Still there were questions over how such different characters could combine in harmony, but the duo sticks together “like flour and water to make that slow dough.” Those nagging public expectations bothered Andre especially, as behind his increasingly confident exterior, he was just a young black male finding himself on wax and fleeing from expectations.

"Now question, Is every nigga with dreads for the cause?

Is every nigga with golds for the fall?

Naw, so don't get caught up in appearance

It's OutKast, Aquemini, another black experience."

Although both members of OutKast are highly quotable, when it comes to poignancy Three Stacks comes up trumps as Aquemini’s wise owl. That power balance has not always been the case in their career – for one thing, Speakerboxxx stomps all over The Love Below – but the Andre of ’98 is simply untouchable. While Big Boi excels on hook-writing duties – ‘Slump’, ‘Skew it on the Bar-B’ and ‘West Savannah’ being particular highlights – Andre’s cadence is so often the thing to hoist songs up to strange, uncharted heights, and his blatant star quality is the propeller for Kast’s success. It wasn’t just OutKast for which he was the driving force either – hip hop itself was growing stale at the end of its golden age, and Dre was at its side with a head full of new ideas. Some of these he worked into the music as he grasped further control over the group’s production, while others were written plainly into the lyric sheet as pointers for his peers: “instead of bitches and switches and hoes and clothes and weed, let’s talk about time traveling, rhyme javelin, something mind unravelling.”

But Aquemini is not the work of one man, or even two men, it owes just as much to the dungeon – Outkast’s studio, sanctuary and spiritual home, placed at the very centre of the earth on ‘Da Art of Storytellin’ (Part Two)’. The song is set in the middle of a frantic, Mr DJ produced apocalypse, but as the four horseman loom and the sky turns electric blue – Andre and Big Boi race back to the dungeon to record one last song. Unlike so many modern day records, Aquemini wasn’t written between sterile industry environments or threaded together from files in an inbox; it has the energy and excitement of hands-on collaboration. You can literally hear the creativity buzzing around in the background, from local church musicians lending their brass and vocals, to Organized Noize and Goodie Mob coming through the studio as Raekwon passes Hennessey around the recording booth.

It might sound trite to say that it feels like you're in the room listening to ‘SpottieOttieDopaliscious’, but there's a warmth and intimacy to the recording that’s added by the dungeon ambience at the back of the mix. The levity of those Reggae horns is what first jumps out, but its magic is that it’s been made to sound almost spontaneous. In two of their best verses, Andre captures a bow-legged girl and an Atlanta night fight in his poetic sprawl, while Big Boi advances the story of blossoming young love – “her neck smelling sweeter than a plate of yams, with extra syrup”. As the recording fizzles out you can almost sense the room locking eyes, grinning in satisfaction and praying that somebody hit record. Classic rap songs have a habit of bring clinical, note-perfect productions, but how many sound this organic?

It’s true, nothing on Aquemini sounds cold or calculated, and yet the reason it has stood the test of time is that there are so many moments of true precision. ‘Da Art of Storytellin’ (Part One)’ stands out for its grim, word-perfect depiction of hood opportunities, and the stories of Suzy Screw and Sasha Thumper are as relevant today as they were in ’98. You can trace the influence of a song like that through the last fifteen years of great rap writers, most recently with Kendrick Lamar who even tips his hat to it on ‘The Art of Peer Pressure’. Kendrick particularly takes clear inspiration from this period of OutKast – his style is almost a fusion of Andre and Big’s, treading the same path between bravado and empathy.

You could be here all week mapping out the album’s influence – far from restricted to the southern states – but it resonates especially with any rapper who has been marginalised by rap itself. The echoes of ‘Return of the G’ on Danny Brown’s new album are no co-incidence, and the eccentric make-up of today’s rap industry owes a lot to the bold steps taken on Aquemini. The album’s main theme, then, is freedom in all its forms, and the penultimate ‘Liberation’ is its nine-minute protest song for the cause. The self-produced epic features only brief contributions from OutKast themselves, who take a backseat and allow the Dungeon Family’s Cee-Lo Green, Big Rube and Erykah Badu to take the lead. Andre and Big Boi create just a platform of a song, but their message is responsibly carried over a weary piano motif and hippie, campfire percussion.

“You shake that load off and you sing your song

Liberate the minds, then you go on home”

But while the influence of Aquemini will live on in various different forms, OutKast weren’t built for modern times. Even fifteen years ago they were warning against the dangers of modern technology on ‘Synthesizer’, and back then Microsoft Encarta was about all they had to worry about. Once pioneers of style and substance, they were heading away from rap when they left us, and it’s difficult to know where they’d fit today alongside the myriad of sounds spewed up onto the internet every day. It’s to their credit that they’ve kept their distance. Sure, Andre has mastered the art of event guest verses and Big Boi is still reliably spitting solo over whatever he feels like – be it Organised Noize, Little Dragon or El-P – but for now OutKast the group rests in peace. Should they return it’ll be because – and only because – the pair has something worth saying, but in lieu of a reunion let Aquemini be the album that they’re remembered for – their bravest and most complete artistic accomplishment.