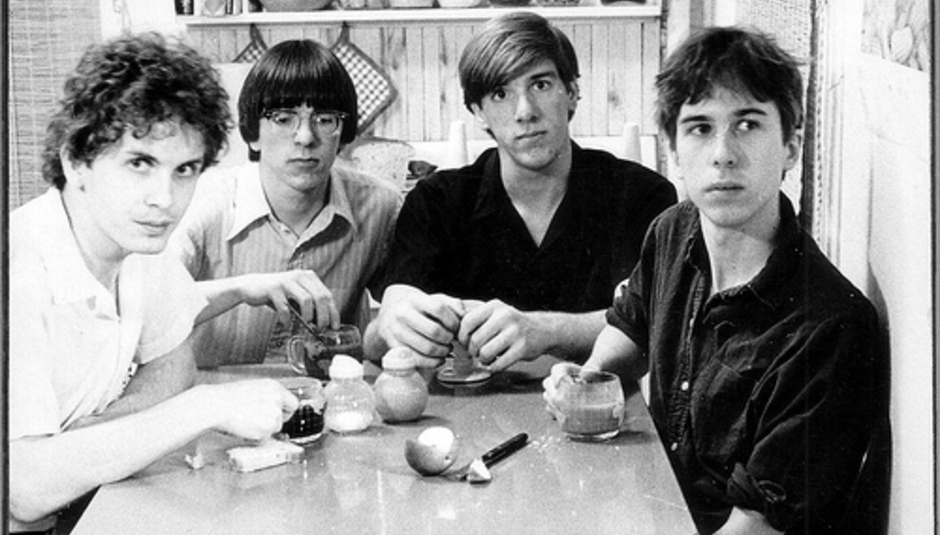

The story of The Feelies reads something like a low-budget soap opera. Despite forming in the late Seventies during punk's halcyon days, it took them a further three years to release their first record. Nevertheless, a combination of frantic live shows and off-kilter rhythms ensured their reputation blossomed outside of their native New Jersey, culminating in growing London-based labels Rough Trade and Stiff Records releasing their first single 'Fa Ce-La' and long player Crazy Rhythms respectively.

However, members came and went soon after setting the merry-go-round of personnel changes which saw them briefly dispense with their moniker on more than one occasion. Five years on, the established core of the band - dual guitar-cum-vocalists Glenn Mercer and Bill Million - reformed the group and released Crazy Rhythms' long-awaited follow-up, The Good Earth, albeit featuring a sound so refined it was barely recognisable as being by the same artists as its predecessor.

Video:The Feelies 'Crazy Rhythms'

Their recording career spawned a further three albums over the next five years, none of which came close to mastering the general uneasy rawness of their debut or sheer bloody-minded persistence of its follow-up, and it was no surprise when Mercer and Million finally called time on the band soon after the release of fifth long player Time For A Witness in the latter part of 1991.

Having achieved something of a cult status over the previous decade or so, not to mention being namechecked as major influences by the likes of Sonic Youth, REM and Weezer, it came as no surprise to see The Feelies announce their return amidst the post-millennial plethora of reformations last year. Last month's well-received Crazy Rhythms performance as part of ATP's Don't Look Back series heralded something of a return to the public eye, being suitably rounded off by Domino Records' timely re-issue of their first two seminal and difficult-to-get-hold-of full length collections, the aforementioned Crazy Rhythms and The Good Earth.

Reared on a diet of The Velvet Underground, Jonathan Richman and Tom Verlaine, Crazy Rhythms marked something of a languorous statement of intent from the New Jersey four-piece back in the spring of 1980. Although punk had been and gone, the record's aloofness and randomly assembled running order ensured a timeless quality soon to be associated with many of their peers who'd influenced the band right from the outset.

Although mainly focused on Glenn Mercer and Bill Million's sinewy guitar breaks and occasional veers into solo territories, Crazy Rhythms owes just as much to the way bassist Keith De Nunzio and drummer Anton Fier steer the backline through a crux of additional forms of instrumentation as cowbells, castanets and tom-toms wrestle with their more traditional bed fellows for pride of place throughout the record's nine pieces.

What's more, like their undoubted heroes The Velvet Underground, The Feelies wouldn't know the meaning of a concept album if it beat them round the head 15 times with a jackhammer. Instead, Crazy Rhythms continuous lack of flow is what adds to its everlasting charm, in that under no circumstances could this ever be accused of being a calculated record aimed at any particular target market or audience. Bereft of any logical running order or theme, Crazy Rhythms sounds like it was written and recorded with little purpose other than to create one pulsating musical experiment after another, and for the majority of the time their carefree approach pays dividends.

From the short-but-sweet pop savvy of 'Fa Ce-La' and 'Raised Eyebrows' through to 'Loveless Love' and its dizzying build-up that lasts almost three minutes and the masterful 'Forces At Work', which takes its cue from 'The End' by The Doors and wraps it round a halo of jagged guitars and angular curvatures, Crazy Rhythms undeniably stands out alongside The Violent Femmes self-titled debut and REM's Murmur as one of the more aspirational collections of the US underground's rising alternative rock scene. Furthermore, as a record it still stands the test of time today, and even the inclusion of a raw take on The Beatles 'Everybody's Got Something To Hide (Except For Me And My Monkey)' can't detract from the fact The Feelies really were one of a kind at this moment in time. (9)

Soon after Crazy Rhythms' release, the world caved in on The Feelies, literally. De Nunzio and Fier departed, and Mercer and Million retreated back to the New Jersey underground in search of another group of similar musicians they could share ideas and eventually record with.

Having tried their hand alongside several noted players on the local circuit, they decided to go with bassist Brenda Sauter and joint percussionists Dave Weckerman and Stan Debeski, initially playing under several different names and experimenting on various styles and genres (track down the album Shore Leave if you can, released in 1986 under the guise of Yung Wu but featuring all five of the aforementioned members) before settling on the mutual decision to return as The Feelies and set about recording a follow-up to Crazy Rhythms.

The decision to get self-confessed fan Peter Buck on board as co-producer may have been something of a gamble at the time, but bearing in mind the heavy influence at the time of psychedelic chancers such as The Long Ryders and The Othermothers, it was perhaps a bold move in hindsight as The Good Earth actually sustains a warm presence some 23 years on, in the same way Primal Scream's Sonic Flower Groove is also looked back on as a hidden treasure rather than odious artifact of disdain.

'Slipping (Into Something)' and 'Tomorrow Today' both revel in a heady mix of nostalgic psychedelia and forward-thinking arrangements, and undoubtedly owe a small part of that to the inventiveness of Buck, more than likely already well on the way to semi-constructing his own outfit's era defining Document around the same time. One thing that does often tend to get overlooked is that The Feelies had an uncanny knack for writing the most simplistic of pop songs, as ably demonstrated by both 'When Company Comes' and 'The High Road' respectively.

Although technically a very different band to that which recorded their debut some six years previous, The Good Earth still retains a good deal of Mercer and Million's sensitivity and enthusiasm, and even though the wilful abandon of Crazy Rhythms is less obvious here, the fruits of its labours deserve to be appreciated today. (7)