In 2016, the artist Geneviève Castrée died after a battle with pancreatic cancer. Barely 35, she was survived by her husband, Phil Elverum, and their one year-old daughter. Long known for his work as The Microphones and later Mount Eerie, Elverum set about capturing the toxic shock of this loss in a collection of spare, harrowing songs that documented, in vivid detail, the later days of Geneviève’s life, the chasm left by her absence, and the grief he felt through it all. These raw reflections, written and recorded in the very room where Geneviève passed away, were released as 2017’s A Crow Looked at Me, an album that quickly became Elverum’s most beloved and critically-acclaimed work in years.

To say that these songs were 'raw' is not to offer any kind of platitude. It is not the same as saying that Elverum writes 'from the heart,' or more simply, that his music is 'sincere.' Brutally stripped of the metaphor and allusion that couches so much other songwriting on the topic, these 11 songs detailed the daily reality of death and the agony which accompanies it to the point that they made me wince. A Crow Looked at Me found the memory of Geneviève embedded in everyday objects: the mail she still received, items she had thrown into the trash before her passing, the place she used to call home (“I watched you die in this room/then I gave your clothes away/I’m sorry”). It balked at the fragility of Elverum’s memory of her (“… these photographs we have of you/are slowly replacing the subtle, familiar/memory of what it’s like to know you’re in the other room”). The knife was occasionally given an extra twist through reference to the daughter they had together (“our daughter is one and a half/you have been dead 11 days”). It found, above all, that mortality pays little respect to our wants, needs, plans, hopes, and dreams.

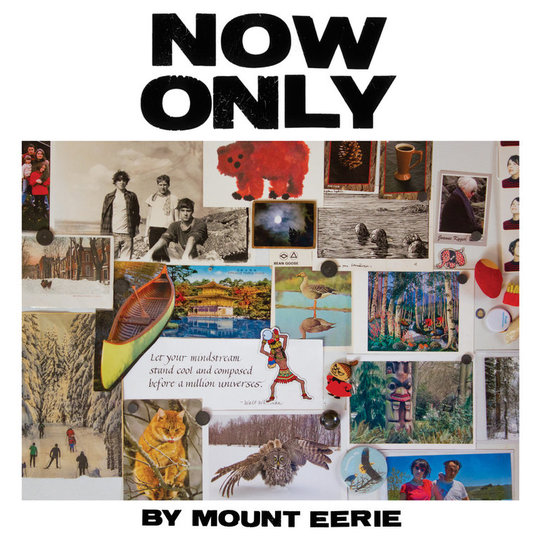

A year on, Now Only continues to trace the trajectory of Elverum’s grief. These are still songs about Geneviève and her absence. Much like its predecessor, it is also at pains to depict the stark reality of death instead of diluting it as poetry. Statements like “but you’re sleeping, out in the yard now” are no sooner sung than retracted. “What am I saying?,” Elverum asks himself. “No one is sleeping.” But where the purview of A Crow Looked at Me was the gut-punch felt in the immediate aftermath Geneviève’s death, this record captures Elverum as his grief “becomes calcified”, as he attempts to pick up the remaining pieces, and, somehow, resume his life. Throughout, we hear him attempt to work out precisely what Geneviève is to him now; where she sits on the vectors between person, memory, ghost, and the material objects she left behind. It is a question and contradiction boldly captured in the record’s opening two lines: “I sing to you/you don’t exist.”

In these more distanced meditations on death and mortality, one theme that emerges is the absurdity that Elverum finds in the very act of carrying on. But, as we are reminded on the title track, this absurdity is also magnified by the cruel success of A Crow Looked at Me, something in which Elverum is at least able to find a kind of morbid humour. “The next thing I knew”, he sings, “I was standing in the dirt, under the desert sky at night, outside Phoenix at a music festival that had paid to fly me in, to play these death songs to a bunch of young people on drugs.” This observation dovetails into an anecdote about an evening spent rattling around a backstage area in the company of Weyes Blood and Father John Misty. He concludes: “to be still alive felt so absurd”, before launching into a perky refrain befitting Randy Newman, but sung to the words “people get cancer and die/people get hit by trucks and die/people just living their lives get erased for no reason/with the rest of us averting our eyes.”

Moments like this aside, Now Only is largely cut from the same musical cloth as its predecessor. Elverum’s style, as ever, has a quite literary quality about it, his delivery meandering—at times understandably deflated—with shades of Leonard Cohen and contemporaries like Mark Kozelek. It would almost feel like stream-of-consciousness, were his observations on the absurdity of his quotidian existence not punctuated by insights far too piercing to be off-the-cuff. But although Now Only is musically similar to A Crow Looked at Me, its scope is also broadened, at least partly reemerging from the catatonia imposed by Geneviève’s death. Most obviously, these six songs are far longer than the short, intense vignettes of A Crow Looked at Me, its longest (‘Distortion’) lasting almost 11 minutes. And although the soft flow of a nylon-stringed guitar is still Elverum’s weapon of choice, here it is embellished with more varied instrumentation: a grunge-y stab of overdriven guitar punctuates the beginning of ‘Distortion,’ and a fog of static briefly envelops ‘Earth’.

All too often we equate songwriting with a kind of poetry. But in Geneviève’s absence, Elverum finds no use for poetry, or at least he finds that poetry is not up to the task of capturing his despair. Instead, on Now Only as on A Crow Looked at Me, Elverum assumes the role of documentarian, exorcising his grief by painfully recording its every detail in song. Telling that in a recent interview, Elverum noted that 'I had more to say still. And I didn’t want to stay in that feeling of A Crow Looked at Me. I knew the only way out was to continue writing songs. There wasn’t even really a gap in the production. I just kept writing.' Like its predecessor, Now Only lays profoundly bare Elverum’s grief. But although it is often an excruciating listen, it also finds room to step, however briefly, outside of the agony that marked its predecessor, if just for long enough to suggest that Elverum is, somehow, beginning to find some relief in the unbearable.

-

9Sam Cleeve's Score