Consciously or unconsciously, it’s more than likely that most folk will have a certain level of awareness of Henryk Gorecki’s 3rd Symphony, or as it’s often referred to, ‘Symphony of Sorrowful Songs’. There are a couple of reasons for this: firstly since its re-release by Elektra-Nonesuch in 1992, it sold over a million copies, and secondly it has seeped into popular culture through various guises, be it on soundtracks like Terrance Malik’s To the Wonder, or as sampled by Lamb on their 1996 record ‘Gorecki’. Through the very fact there are a million physical or digital copies knocking around, and its use in other artistic ventures, mean it has hung in the air for many years now finding its way into the collective consciousness.

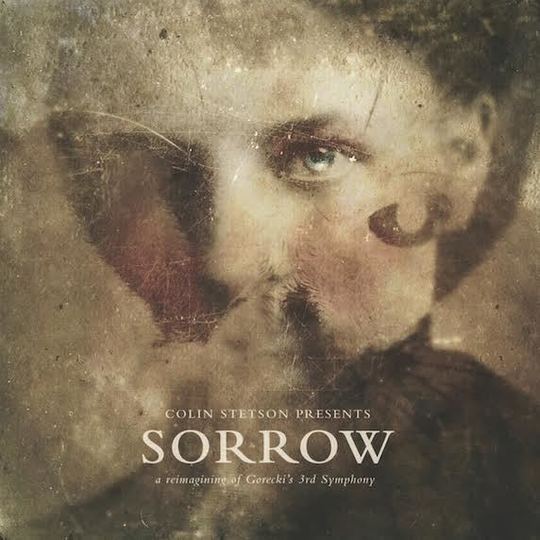

You’ve gotta hand it to Colin Stetson: to take on a much-loved piece is one thing, but when that music happens to be from the often rather haughty and lofty classical world - well - that takes balls. In Stetson’s case, he has gathered together his massive bass saxophone (amongst other reed instruments), a collection of extremely talented friends, and somehow managed not to let the weight of expectation asphyxiate what has turned out to be an astonishing re-working of this, already, transcendental music.

Not for one moment is Sorrow a tentative or hesitant ‘cover’. Stetson boldly approaches the work with an obvious respect, but he is never beholden to the original. The symphony is comprised of three movements and it is towards the end of the first that the most striking additions reveal themselves. Greg Fox, of the black metal band Liturgy, unceremoniously wades into the fray with a crescendo of heavy percussion. Now, you can already hear the cries of ‘the horror, the horror’ from unimaginative old crusties. But this addition is not made in the spirit of being controversial for controversies sake. And it’s not an experimental misstep. It genuinely adds to and enhances the piece. Stetson is stepping it up a notch; inexplicably adding drama to the music that is already steeped in powerful emotional sensations.

For many, the staggering emotionality of the piece is inextricably linked to the holocaust. Gorecki is Polish, and the second movements lyrics are taken from a note of a teenage girl left on the wall of Gestapo headquarters. These facts, amongst others, have led many to believe it was the composer's response to the atrocities of the Second World War, but it was an interpretation that he rejected. He was happier to explain it in more general terms, as music that laments wars affect on the relationship of mothers and their children. Similarly, Stetson takes a view that the music, as he recently explained when talking to DiS, “perfectly encapsulates the convergence of joy and sadness, that freedom that comes from reaching ones ultimate capacity for sorrowful feeling.”

It is in the second, and probably most famous, movement that we get to the marrow of that sorrowful feeling. Much of this is communicated through his sister, and mezzo-soprano, Megan Stetson’s vivid vocal performance. Like much of the recording, the tone is notably darker, which is something Stetson has conceded, and he explained, “it's this hyper realised or exaggerated view of the emotionality of the piece.” Again you might think that considering what many tie that emotionality too, he may be on rocky ground by manipulating it. But, the tone can only get darker when nearly 30 years after the original composition, we still keep making the same damn mistakes - you only have to turn on the TV or read the news to see this startling recognition in the number displaced Syrian refugees. In many respects, Stetson has freed the piece from its ties, taken a pair of bellows and aerated it, widened its scope and opened it up. Evidently, it speaks just as loudly in 2016 as it did in 1992.

However sensitively, or otherwise, he has approached this piece of work it will no doubt have its detractors, which is a shame. For as much as its fullness could be seen as counterintuitive to the music’s harmonic minimalism, the addition of jazzy reeds, black metal drums and electric guitar really do serve it well. And jeez, it’s not like he’s gone out and done a drum ’n’ bass remix or anything. What he has done is somehow make this work more immediate and pressing, and its density comes without compromising the minimalism of the piece. Projects like this suggest precious protection of art is not only cynical but counterproductive to the quest for great new things. And, it is a work that, thematically, has lost none of its potency - we may not all be mothers, but we are all children of them, and so for sorrowful feeling read empathy.

-

10Bekki Bemrose 's Score