When will the battle be over? When you no longer have to appropriate the cultural forms of dominant (or different groups) to prove you can do them just as well? When you no longer have to parody, subvert, or exaggerate representations by the dominant group to expose their absurdity? When you no longer have to forge your own language by looking in the cracks between extant idioms, but can avail yourself of all? When dichotomies are out of the question, and even the dialectic between Us and Them ceases to be implicit in the conversation-that-is-art, and you simply are – speaking in your own voice at last?

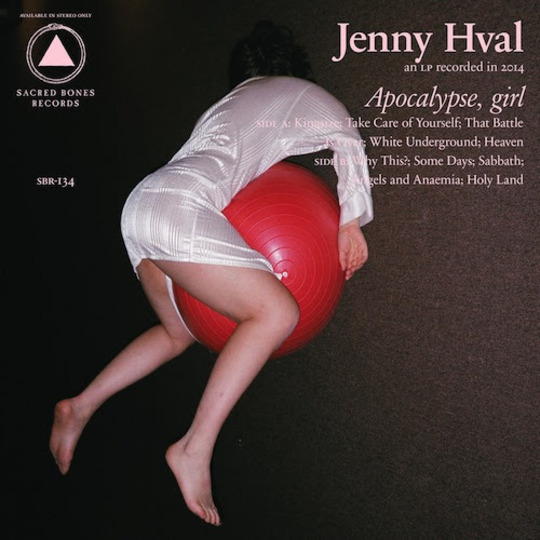

Gender and the process of gendering remain omnipresent in the lyrics and music of Jenny Hval, who, as of album #7 may no longer be referred to as a 'prodigy', in that she’s now more like a confirmed woman-of-juno (that being the under-used feminine form of ‘genius’). 'That Battle is Over' – her ironically titled single – reminds us that we’re still at the fourth wave of feminism, and while the album’s soundscape largely dispenses with signifiers of confrontation (the dissonance, noise, and fragmentation of her mid-period albums), it’s also a long way from the sweet Scandi-pop of her earliest incarnation, Rockettothesky, where she smuggled subversive sentiments via her lyrics, delivered in an almost operatically affected soprano (as if to hint at the performance that is gender, without forcing the issue).

Instead, Hval adopts the kind of electric organ you’d find in a small suburban church, as her lead instrument; The Boatman’s Call aside, it’s most likely to evoke boring Sundays, and twee outdated values you can’t believe anyone could hang onto. Sonically, then, Apocalypse, Girl shifts further away from the Armageddon that was Viscera where (to adapt a quote from The Holy Bible) she ‘…wanted to rub the human face in the c--t and force it to look in the mirror’, by personifying her genitals as something monstrous and c--k-devouring. By this point in the narrative, the Great Unveiling has taken place (the etymology of 'apocalypse', innit) and what’s been revealed isn’t angelic or demonic. The feminine quintessence isn’t fragile, vulnerable, or delicate any more than it’s visceral, bloody, or sweaty. In the sung-spoken lyric – somewhere between bored and wistful – Hval reveals that she’s statistically more likely to get breast cancer; that she’s a quarter Danish; that she’s now free to consume pretty much whatever she wants; in short, she’s a person not an ideal…

…which may be the most dangerous thing for an artist to admit: that there is no feminine mystique, simply a gendered inflexion (one way or another) to the everyday business of being human. Mysticism and baroque metaphors aren’t discarded entirely, but they are toned down: where Hval previously alluded to Greek mythology and canonical Great artists (with a capital G), her allusions, here, are largely confined to an aetiolated Christianity that presents suburban tedium as the End of History, or Heaven on Earth. If that sounds like a sentiment from Talking Heads, well, in spirit it is, if not quite in sound. To be more precise, Hval wavers between two different muses for women born in the Eighties: Julee Cruise (who Lynch & Badalamenti chose to epitomise femininity at its most sanctified and unattainable – soundtracking the descent and ascent of Laura Palmer), and Laurie Anderson, who uses an androgynous persona to whisper stark truths, deadpan stand-up comedy, and America’s secret histories, as a conduit between the avant-garde and pop. Thus, it’s unlikely to be coincidence that Hval name-drops Big Science within a minute of starting her weirdest spoken-word yet on the subject of masturbation (yup, it’s not her first). Across the course of the album she explores what she calls 'soft dick rock' (confronting males with their redundancy), and if the music isn’t always as hip- and heart-moving as Holly Herndon, it’s definitely pushing the concept of album-as-platform; alongside Herndon’s 'Lonely at the Top', these are bound to be some of the most talked about lyrics of the year. On the final track, “Holy Land”, Hval refrains from having the last word on whether the battle is won: her voice simply merges into wordless, fluid sound; it’s anti-climactic, without feeling defeated, or drowned.

From a melody-craving, lowbrow perspective, something has been lost by renouncing the ethereal qualities of female voices, harmonised, multi-tracked and processed to evoke an uncanny other-world. You have to turn Girl up loud to hear the 'meshes of voice' that make this a more complex album than on first impression. Nonetheless, Meshes of Voice ('with Susanna', which represented a career-high for Hval and won the pair a Norwegian Grammy) was only a year ago, and we can expect her to continue trying on the many faces of (Wo)Mankind for many years to come.

-

7Alexander Tudor's Score