Could there be a more reviled instrument in pop and rock than the saxophone? That most flatulent of all brass instruments, more likely to soil an arrangement than a trite key change, or inane melody…? Granted, the vocoder may have been responsible, in the past decade, for adding more layers of processed cheese to the already fattening pap listeners are fed, but it’s usually pretty easy to draw the line between hip and unhip by identifying the saxophonist in a band’s line-up.

What’s unexpected about exploring classical minimalism, post-punk, no-wave, and the outer fringes of jazz is how much the saxophone proves capable of a sonic assault to rival electric guitars, if not surpass them, with a vast tonal range and sense of physicality that doesn’t depend on effects pedals and amps (which can, in turn, trick guitarists into clichés). Pushed to its limits, the saxophone is one of the few instruments that allows the player to produce natural distortion that provides the visceral thrill of almost-but-not-quite losing control. The big names in free jazz are Zorn, Ayler, and Coleman, but check out the saxophone concertos by Phillip Glass; the sax-led punk-funk of James White & The Contortions; The Pop Group; jazz-metallers Zu; improv nights like Boat Ting (at Temple Pier).

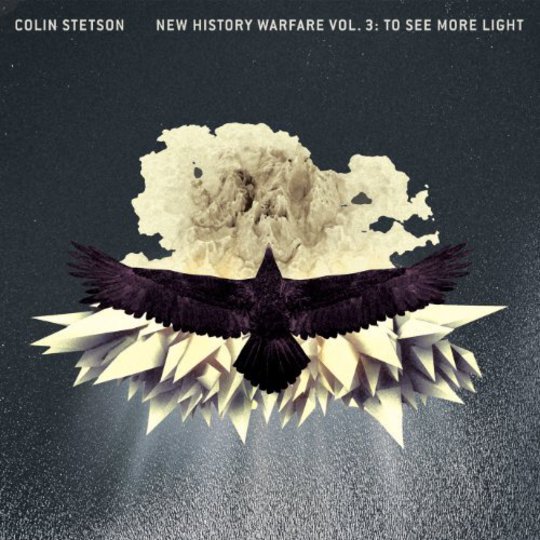

It’s one thing to say that Colin Stetson is the saxophonist on Arcade Fire’s The Suburbs and Bon Iver’s second album – so what? you might say, There’s always an exception to the rule that sax ruins a song… In fact, Stetson’s the exception who’s made solo albums that appear high up in DiS, Wire, and Pitchfork end of year lists. Unlike Owen Pallett – another solo artist who broke out of the 'supporting musician' ghetto with his albums as Final Fantasy – Stetson’s earned his acclaim without much concession to normal song structures or more than a few tracks with conventional vocals.

Track by track, this means war: the relentless pummelling of metal in motion; often aggressive or chaotic, but using scales to evoke a sense of discipline too, and the subordination of the individual to a mechanical solidarity. For its abrasiveness, brute force, and determination to push the instrument to its limits, Stetson’s New History Warfare 3 should delight anyone bored with noise, power electronics, industrial, and post-rock – or anyone who can’t get enough of the above, and (in particular) loved X-TG's (i.e. Throbbing Gristle’s) Final Report.

On the other hand, Stetson’s equally at home with classical minimalism: with its rapid scales, simultaneously blasting and percussively clattering on the (close mic’d) keys, what the music of the New History Trilogy most resembles is Steve Reich’s Different Trains, or Glass’s (wildly underrated) Saxophone Concerto and “Mishima” String Quartet. What he’s added is the post-punk energy of a band like This Heat (who contrasted the demented shriek of woodwinds with the industrial onslaught of bass and drums) or, you could say, he’s transformed Glass & Reich much the same way Godspeed You! Black Emperor transformed Morricone and Arvo Part. (Stetson’s toured with GY!BE, and more than deserves some kudos by association.)

While the recordings on Volume 3 involve few takes and no overdubs, his producer deserves a shout out for his own sake: Ben Frost stole the show at Michael Gira’s recent Mouth to Mouth concert with a devastating set of power electronica, heavily manipulated guitar, and two drummers, in spite of opening for Swans. Like New History Warfare, Volume 2, Frost’s last album, By the Throat was a Wire album of the year, and on the strength of his set, I’m hoping his next will be an instant classic that revitalizes post-rock, or sends journalists scrabbling to christen a new hybrid genre. Nothing less. Here, Frost mixes the sound of Stetson’s circular breathing high up so that the sighs, grunts, groans, and howls are as expressive as any metal vocalist, and as unnerving as the wolf-sounds on his own album.

Having fawned over Frost, it seems only fair to mention Justin Vernon who actually sings on Volume 3, taking over from Laurie Anderson who guested on Volume 2. He’s perfectly fine on the hymnal opening, and covering 'What Are They Doing in Heaven Today?', but not much more than decorative. As one of the great conduits between pop and the avant-garde for more than three decades, it’s fair to say that Anderson nudged the previous album towards being one of the most powerful responses to the War on Terror, yet; an avant-garde response to file alongside The Disintegration Loops by William Basinski. Nonetheless, Volume 3 is essential listening and another triumph.

-

8Alexander Tudor's Score