Thirty-two years on from the release of Bruce Springsteen's Darkness on the Edge of Town, his resurgent cred with the alternative crowd is rooted not in that record, but rather Nebraska and The Ghost of Tom Joad, his two exceptionally stark acoustic records chronicling the decline of the American working classes post-Vietnam. In fact there are plenty who maintain that Nebraska is his only good record. Which is funny, because some of those people probably worked for NME in 1978, the year the then punk obsessed mag made Darkness... its album of the year.

Why the fall out of fashion? You can point to the bombast and ubiquity of Born in the USA, but really a lot of it was down to the NME’s Julie Burchill, who absolutely demolished The Boss's 1980 double album The River, with a vehement review – (‘great music for people who've wasted their youth to sit around drinking beer and wasting the rest of their lives to’) - that more or less served time on the UK music press's love affair with the man. In retrospect some of her words seems unfair (anyone who doesn’t like the title track is basically a monster), but in a Britain where punk’s sneering echoes still resounded deafeningly and the likes of Joy Division and PiL had just had hit records, Springsteen must have seemed like a bit of a pranny coming out with songs like 'Sherry Darling' and 'Crush on You'. I mean, I’m sure there were kids who liked ‘Hungry Heart’ and ‘Death Disco’ equally at the time, but they must have been exceptionally mixed up people.

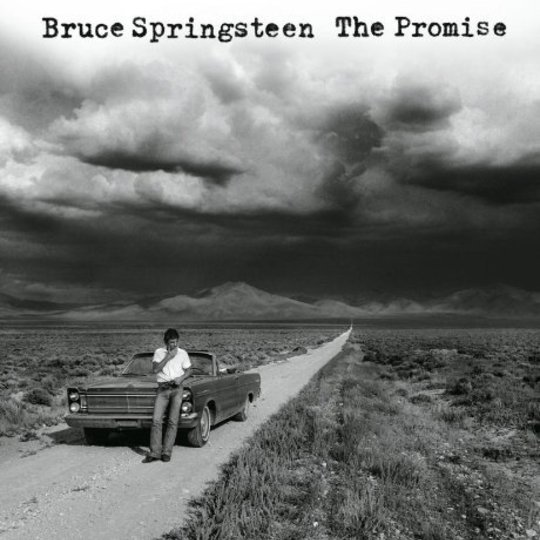

Anyway, it’s within that context that it’s interesting to frame The Promise, because one of the most fascinating things about this double CD of quality offcuts from the Darkness... sessions is how deliberate it reveals the parent album’s hard, lean, bleak tone to have been. Due to protracted legal wranglings, Springsteen spent the three years between Born to Run and Darkness... unable to release music; rather than take up a hobby or get a job or whatever, him and the E Street Band simply went into the studio and recorded a shedload of material until such point as they were allowed to release some of it. But where the ten songs that went onto the immaculate Darkness... are pessimistic, stripped down, and – in the case of ‘Adam Raised a Cain’ and ‘Streets of Fire’ – possessed of a blue collar fury to rival punk’s art school nihilism, The Promise demonstrates that he’d in no way abandoned the romance, optimism and expansive dreamer’s anthems of Born to Run. He’d just chosen not to release them. To be honest, that was a pretty good decision: Darkness on the Edge of Town feels like a '78 record; The Promise has more of a '58 vibe. It's old fashioned, somewhat corny, would not have been beloved by Burchill, and is most certainly not the ideal starting point for the curious Springsteen novice.

For a double set of studio discards it's also excellent, though how longstanding fans take it will likely vary. If you think Born to Run and before was his peak, you’ll probably go nuts for a double CD cut from similar musical cloth, if lacking quite the same gravitas and epic sweep. If Nebraska or Born in the USA or even Darkness... itself are yer faves, you're liable to find all 22 tracks of The Promise a little gloopy in one sitting. Even so, that's 22 new(ish) Springsteen songs of top notch craftsmanship, with no bloopers and a handful of genuine gems.

Said gems, then include ‘Racing in the Street (’78)’, a monumental full band version of Darkness...’s piano dirge centrepiece. It's possessed of so much rough power and musical force that you can kind of see why it was shelved for the more introspective take: its pyre-like crescendo of squalling harmonica, surging guitars and epic drummage slightly steamrollers the bitter pathos of the last few verses (“She stares off alone into the night/With the eyes of one who hates for just being born”). But if you can see why Springsteen dropped it, it’s a jawdropping opener, and one of the only two songs here that really successfully combine Darkness...’s bleakness with Born to Run’s widescreen vistas. That other song is ‘The Promise’ itself: long the holy grail of unreleased Springsteen tracks (though he put out a rerecorded version in 1999), one guesses he left it on the backburner on grounds of it being yet another song about a working class car aficionado with shattered dreams, but for all that it is a genuinely superbly wrought example of said song. And then there’s ‘Because the Night’: sure, the Patti Smith Group’s is the definitive, weightier version but Springsteen’s own, more throwaway take is still great fun, and sits well on the record, for all its familiarity.

And then there are 19 more songs, which I’m not going to go into at length, but for starters you’ve got your echoey, Fifties-style balladry (‘Fire’, later a hit for the Pointer Sisters), ecstatic doo wop dizziness (‘Ain’t Good Enough For You’), soaring, brassy celebrations of being alive (‘Gotta Get That Feeling’), melodramatic, rinky-dink pop (‘Outside Looking In’) and schmaltzily uplifting Spector-ish torch songs (‘Someday (We’ll Be Together)’). Nothing feels unfinished, sketchy, or b-side ish, and as individual tracks, there’s a lot to love here. That said, if you’re going to characterise the record as a whole, it does kind of come across as an enjoyable exercise in writing pre-Beatles pop and ballads, rather than anything possessed of the emotional fire and lyrical incisiveness of Springsteen’s best records. That he had the judgement to leave this stuff off Darkness on the Edge of Town probably says almost as much about his talents as the music itself. But keep your sense of perspective and remember that The Promise really is an offcuts record, and you’ll find it’s a staggeringly good one.

-

8Andrzej Lukowski's Score