The first obvious joke on Laurie Anderson’s first proper record for the best part of a decade appears as you – if, indeed, this is how you treat your CDs – burn it onto iTunes. 'Laurie Anderson: Homeland: Pop' the screen announces. Now, Mrs Lou Reed (unless, that is, you consider Reed Mr Laurie Anderson) has been described as many djective- heavy, composite-noun-dependent things, her work many more. But pop music? Yes, her Massenet-meets-a-musical-robot masterpiece, ‘O Superman’, may have very nearly topped the UK charts in 1981, but it’s still something of a stretch, even accepting that in her cocktail of spoken-word melody and electronic illusion one can locate roots that grew into mainstream hits ranging from ‘Everybody’s Free (To Wear Sunscreen)’ to Imogen Heap’s ‘Hide And Seek’.

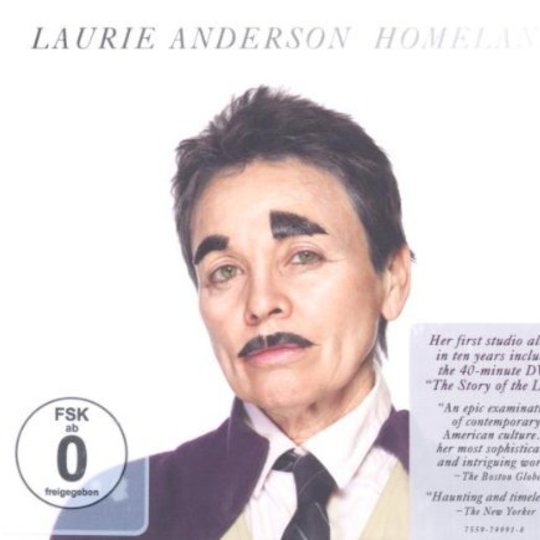

Splashes of humour are an important facet of Laurie Anderson albums – insofar as the first time one hears a track of hers, the instinctive reaction is to chuckle bemusedly, before Anderson’s own recognition of this expertly counters any urge to therefore be dismissive. Wait a minute, I lied before: Homeland’s first gag is its cover, depicting Anderson sporting the moustaches and eyebrows of a 19th century cad, seemingly barely attached. This is the face of Fenway Bergamot, Anderson’s 'voice of authority' alter-ego, created by machine-slowing and down-pitching her vocal to the point that it sounds like an android Carl Sagan.

And so it is to Fenway that Anderson gives Homeland’s glittering 11-minute centrepiece, ‘Another Day In America,’ a synth-swept, Antony Hegarty-flecked voyage that begins as a mesmerising sequence of reflection and anecdote (“_here’s my theory of punctuation: instead of a period at the end of each sentence, there should be a tiny clock, which shows you how long it took you to write that sentence”) and ends an aching study of the contemporary American experience: “What are days for? To wake us up? To put between the endless nights... Another day in America. And oh my brothers, and oh my long lost sisters, how do we begin again?_”

Not, then, a barrel of laughs. In fact, this marriage of reflective storytelling and the plain abstract is a microcosm of the record as a whole. Opener ‘Transitory Life’ begins all Warren Ellis violins and (ill-judged) eastern vocals before remoulding itself into muttered epigrams and Grandaddy-esque melodies. At the other end of the record, on ‘The Beginning of Memory’, the same world-music-ish backdrop accompanies “a story in an ancient play about birds, called The Birds”. And ‘Thinking of You’, Homeland’s second most straightforwardly pop-like moment, circles around a chorus about snow or something via a strings-setting pitched halfway between the Beatles’ ‘She’s Leaving Home’ and the sort of orchestra-thing Sufjan likes to do.

Second because of ‘Only An Expert’, a track that, despite being a biting indictment of the way financial, media, governmental and business elites gather outrageous influence by creating problems only they can solve, represents Homeland’s brightest and most immediately-memorable moment. Sing-song-sarcastic takes on both the usual and less-usual suspects (Al Gore, say – “but when an expert says it’s a problem, and makes a movie about the problem, and wins an Oscar about the problem, and gets a Nobel Prize about the problem...”) are coupled with squelchy bass-drips, techno throbbing and a chorus that tacitly mocks 60 years of meaningless repetitive choruses. All together now: “Only an expert can deal with a problem. Only an expert can deal with a problem…”

So far, so inconsistent. Or not, actually. Indeed, Homeland’s biggest achievement is to sculpt a lot of minutes of material – both new tracks and ones she’s been playing live for years – into something that feels textured and whole, rather than fatly fragmented.

But how? One need look no further, I think, than Anderson’s famous homemade magnetic violin. For the Warren Ellis comparison only stands up for half the record – its string-section in fact building and building throughout into something that literally explodes halfway through ‘Dark Time In The Revolution’ with the squeal of the Psycho soundtrack gone robotic. It is just one musical journey on a record made up of journeys, through poetry, morality, America, through sound itself.

-

8Sam Kinchin-Smith's Score