There was a group of boys in my year at school who self-identified as ‘avant garde’. I remember thinking it’s the kind of thing that should only really be said about you by others – in the same bracket as ‘magnetic’ or ‘genius’ or ‘hot’ – but they were navel-gazing teenagers and were therefore impervious to how they appeared to outsiders. This group of middle-class 17-year-old radicals rebelled in small ways that seemed significant: singularly focused on escaping the creative confines of Worcester town centre, growing their hair dangerously close to the acceptable limit as dictated by the school rules and, most notably, hungrily devouring all sorts of music, the main requirement of which was that nobody else should have heard of it.

They commanded control of the common room CD player, much to the exasperation of most of its inhabitants, who were no doubt keener to listen to the latest Black Eyed Peas release than Bitches Brew. But in spite of, or possibly, given my 17 years’ life experience, because of, their pretentious but passionate take on things, and their seemingly superior level of understanding, I was desperate to join in, to absorb it, even to contribute. The general consensus was that I was too mainstream as a human and a musician, too conformist, not devoted enough to my art. So I sat and listened, sometimes bemused, other times fascinated – and then, one day, they put on Soviet Kitsch by Regina Spektor.

This was out of sorts for them. I’d grown used to hearing 60s and 70s jazz records, so a contemporary and, dare I say it, female musician who sang acoustic songs with verses, choruses, and actual words – well, it took me aback. And because we tend towards music we would like to see ourselves in to some extent, I clung to her. She was a new world to me, beyond Joni Mitchell and Kate Bush, whose music I’d devoured but as things I’d missed – whereas this, this was happening right at that moment. For an album full of songs about life in New York and comments on its inhabitants, fictional, animal, vegetable or otherwise, it felt remarkably relevant to a middle England schoolgirl.

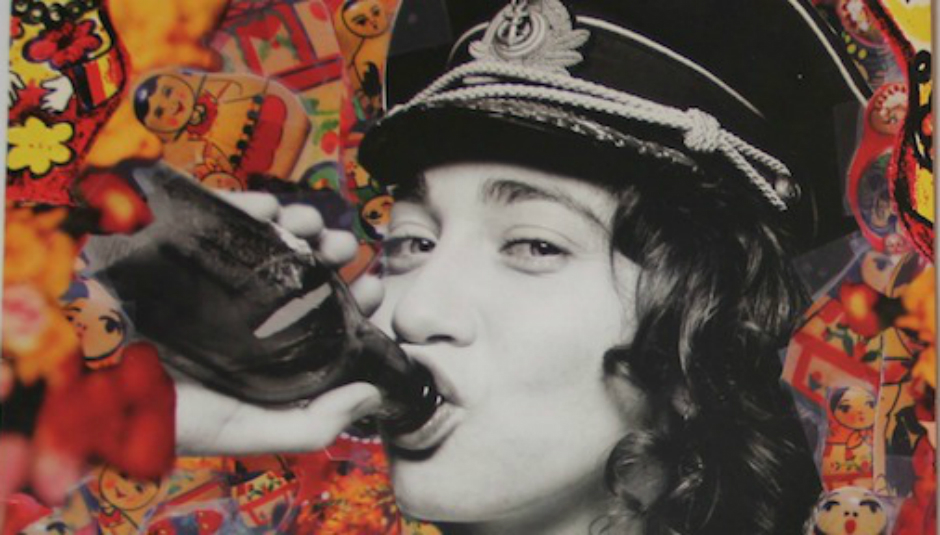

Part of New York’s so-called ‘antifolk’ movement, Spektor had released two albums before Soviet Kitsch: 11:11 and Songs. The latter was recorded on Christmas Day 2001, all in one take, and contains some of Spektor’s most beautiful songs: ‘Samson’, ‘Oedipus’, ‘Consequence Of Sound’, ‘Ne Me Quitte Pas’. Soviet Kitsch was a step in a different direction – less of the jazz influence of 11:11, and not quite as lo-fi as Songs – but was still another self-release in 2003 which, having opened for The Strokes on their Room On Fire tour, was then picked up by Sire Records in all its DIY glory.

Its charm is in its flex. It moves from painting a heartbreaking picture of dealing with cancer and its effect on a family in ‘Chemo Limo’, to wink-and-nudge bedroom humour in ‘Ghost Of Corporate Future’, to a deliberately confused stream of consciousness in ‘Ode To Divorce’. How can you fail to smile at lines like “And you don't love your girlfriend / You don't love your girlfriend / And you think that you should but she thinks that she's fat but she isn't but you don't love her anyway”? Or get sucked into songs that open “Some days aren't yours at all / They come and go as if they're someone else's days/ They go and leave you behind someone else's face/ And it's harsher than yours/ And colder than yours”?

I’d never heard lyrics like them, and I’d also never come across these sorts of Frankensongs – four-minute things with multiple parts, totally different time signatures and singing styles, somehow united by a narrative, however bizarre. It seemed like such a ballsy approach to songwriting to me – as though each line was a tiny rebellion, a two-fingers-up at whatever anti-folk is or was, subverting its subversion. Whoa! Subverting its subversion? You know, if only I’d talked like this 12 years ago, maybe – just maybe – I’d have been accepted into the ranks of the avant garde sixth form common room set. Sigh.