It doesn’t take a social scientist to predict the result of a black rapper in a leather dress shirt walking onstage at a global award show to tell a teenage white girl why she doesn’t deserve her award. Even in 2018, after brandishing support for Donald Trump and positing that American slavery was “a choice”, there still may not have been a more dangerous time for this artist’s career than after the VMA 2009 Taylor Swift incident. In the fallout, Lady Gaga dropped off his planned co-headline tour, and he was then held back from touring on his own due to plummeting sales predictions.

No matter your opinion of the action, being told that one ten-second impulse has stripped you of the ability to tour is a heavy blow to a global superstar—heavy enough to make one think their career is over, and kill the morale to achieve greatness ever again.

What was Kanye West going to do?

In June 2010, still enduring peak backlash, West would put on one of his littlest-known TV performances ever at the BET Awards. This was the world premiere of his iconic bright red suit, sans shirt, plus life-size gold Pharaoh head necklace. Atop a custom-built mountain stage, backlit by panoramic travelogues of snowcaps and clouds, he performed a new single called ‘Power,’ and each time he said the word, a geyser of red smoke would erupt behind him. With the wallop of a rock’n’roll anthem, it sampled King Crimson’s prog rock relic ‘21st Century Schizoid Man,’ and over a tribal chant, his opening lines went like this:

“I’m living in that 21st Century, doing something mean to it / Do it better than anybody you ever seen do it / Screams from the haters, got a nice ring to it / I guess every superhero needs his theme music”

The following year, it was announced that both West and Swift were on the performance schedule of the 2010 VMAs. Swift opened her performance with a full replay clip of West walking up to take the microphone from her. Somehow no one registered this as shameless self-pity, but if that wasn’t enough, she hung her head and sang a song called ‘Innocent,’ which contained such lyrics as “It’s okay, life is a tough crowd / 32 and still growing up now” (West’s age at the time, because you know, she didn’t want to just spell it out for us). The rest of the lyrics ask West rhetorical questions about his childhood, which at the time came off eerily like a dig at his mother’s recent death.

But still, it was September 12, and Aziz Ansari introduced Kanye West at the close of the show. No one had any idea what song he'd even play. Consider, for a second, the colossal pressure riding on this performance. Whatever it was, it would have to address the elephant in the room.

He walked in, wearing his red suit and chains, up to an MPC2000 sitting on a white Greco-Roman pillar, on which he tapped out the piano motif to ‘Runaway.’ Mauve ballerinas glided along the circular white stage. He’s singing again. Calmly, he delivered the melancholic chorus:

“Let’s have a toast for the douchebags / Let’s have a toast for the assholes / Let’s have a toast for the scumbags / Every one of them that I know”

He was somehow both apologizing and not apologizing, singing directly to her while not acknowledging her at all. As he finished and walked off, the audience gave the sort of roaring applause that resounds overwhelmingly even from a TV. For at least one night, he was forgiven. But he could only fully recover if this upcoming album was his best ever.

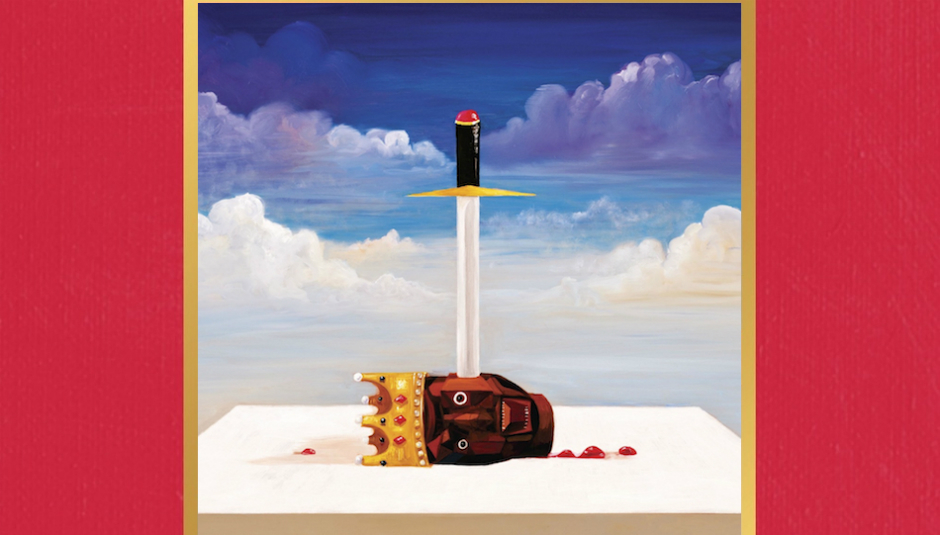

He introduced the album’s five different covers, all by modern Picasso disciple George Condo, most notably the portrait of Kanye making love to a voluptuous half-phoenix woman, complete with Pegasus wings and Dalmatian tail. If you ever wondered where the rappers’ tradition of commissioning world-renown artists for album art began, now you know.

After months working under the alias A Good-Ass Job, he announced the final title: My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy. Just to imagine how it would open, who the guest vocalists would be, how it would close, was a joy of its own. Around that time, I was a high school sophomore, unable to so much as introduce myself to a girl I was attracted to. For a Playstation-raised suburbanite like me, a Kanye album was the only traceable source of confidence.

I stepped up to the Rhino Records counter with a red square in my hand. The clerk, who never so much as greeted me despite being a customer for years, couldn’t contain himself: “This album… this album is so dope, man.” On the walk home, two different cars passed me blaring Kanye verses I’d never heard. I put the disc in my Xbox 360, laid my head between my garage sale Bose cones, and closed my eyes.

Ever since Late Registration, there were only two things you could be certain you wouldn’t hear a Kanye album without: piano and strings. After a satirical British fantasy film narration intro from some new rapper named Nicki Minaj, there it was—the legato F sharp major atop staccato cellos that fluttered like angel wings. The man on the verge of losing it all opens his album with a Mike Oldfield sample that asks a single question:

“Could we get much higher?”

This is the rap game Don Quixote at work, his delusions so vivid he realizes them all.

‘Gorgeous’ was West’s love letter to those who missed him as an emcee after his last record, the all-sung 808s & Heartbreak. To this day, it could be one of the most agile set of verses in rap history. According to Kid Cudi, West’s charge of lyricism was inspired by the incendiary release of Jay Electronica’s ‘Exhibit C.’ The song's three verses are a civil rights microcosm, with lines as deft as, “Is hip hop just a euphemism for new religion? / The soul music of the slaves that the youth was missing?”, to battle rap punchlines like “They rewrite history, I don’t believe in Yesterday / And what’s a black Beatle anyway, a fucking roach?” And to further crystallize his hip hop heritage, he shares the song with Raekwon.

In Star Wars, when a Jedi dies, other Jedi can feel it through their power of the Force, hanging their heads in vicarious agony as they sense a fallen comrade. This is famously known as a “disturbance in the Force,” and you need to know this to understand Kanye's most iconic line on Fantasy:

“Something wrong...I hold my head / MJ gone / Our nigga dead”

Though almost certainly not intentional, Kanye paints a mystical connection to Michael Jackson, one where he’s able to sense that he has died before anyone else even finds out. This is his entrance on ‘All Of The Lights,’ cutting the music to deliver the wrenchingly simple epitaph. It also seems to ask how we would feel if he too died suddenly amidst a public downfall. ‘All of the Lights’ is a many-headed beast of sound and colour, equal parts glimmering paradise and damning inferno, contrasting triumphant horns with haunting lyrics. He won’t give us the light without the darkness:

“Restraining order, can’t see my daughter / Her mother, brother, grandmother hate me in that order / Public visitation, we met at Borders / Told her she take me back, I’ll be more supportive / I made mistakes, I bumped my head / Courts sucked me dry, I spent that bread / She need her daddy, baby please / Can’t let her grow up in that ghetto university"

At the time, West had no daughter. In the portrayal of one who has made worse mistakes than he ever has, West contemplates forgiveness for the unforgivable. (This theme even ties well to the question of continued allegations of Jackson’s unthinkably heinous actions). He is imagining the tribulations of the future, complete with a reference to Borders, the family bookstore chain that sadly shuttered that same year. With his final line “Baby please, can’t let her grow up in that ghetto university”, it comes full-circle – Kanye was raised without his father. Perhaps that’s why losing a role model in Michael Jackson hit so hard. Faced with seeing his daughter suffer the same fate, he realizes that if people never forgive, they only lay a foundation for further disaster.

The song uses light as a MacGuffin for the forces that drive us, be it morality, greed, love, fear. We are all made of light, they say, and the query here is how much light you will seek in your life, whether you will accept the pains with the pleasures, the missteps on your journey to the truth, or remain complacently in the dark.

With Fantasy, West proved that hip hop was something infinitely more expansive than its stereotypes constrained – being the genre to coin sampling, it was a chance to fuse every conceivable sound and genre into one, cohesive album. Few rappers before this ever dared to reach beyond the traditions of couplets over old R&B samples, but Fantasy’s grandiose journey of movements, solos and cadenzas paved the path for new frontiers.

If you were a rabid Kanye fan, you’d already blasted the ‘Devil In A New Dress’ leaked version a hundred times in your car before Fantasy’s release. This is why when it came on the album, at the time the song is supposed to end, you froze at the sound of an electric fuzz guitar solo ascending. A guitar solo on a rap album – this was the world’s introduction to Mike Dean. Bink’s wedding-worthy instrumental fades back in. There is only one rapper in the world with the gusto to cut through this lush climax, and West knew that was Rick Ross. By the time he fired his final lines, “I’m making love to the Angel of Death / Catching feelings, never stumble retracing my steps”, and the guitar solo resumed, I was in disbelief that there were still five more tracks to go. Ross’s sense of imagery, over this twinkling baroque flourish, is a meditation on luxury you’d have expected from Fitzgerald.

While every other song on Fantasy feels meticulously crafted and perfected, ‘Hell Of A Life’ feels like unhinged fun. At the same time, it’s also one the most intricately produced songs of West’s entire catalogue; the fuzzed-beyond-all-recognition bass riff and hydraulic lowrider breakbeat, with that speaker-tearing wall of snares at the end of each phrase. By the time your head stops spinning from the harpsichord arpeggios, you still haven’t noticed the chorus uses the exact melody of Black Sabbath’s ‘Iron Man.’ At the end, the main riff breaks down into distorted 808s, Hentai sex grunts are pitched into chords, and Kanye hyperventilates through a phaser. All the song’s lyrics are about masturbating to Internet porn, somehow equating its joy and intensity to married love.

But as if positioned to portray a post-coital dejection, ‘Blame Game’ follows, a chaotic reinterpretation of Aphex Twin’s ‘Avril 14th,’ featuring a side of John Legend we’ve never heard before (“I’ll call you bitch for short”) that diagnoses the territorial hell of infidelity. The tambourines and snare rolls are sickeningly loud, evoking an inner disorder. For the final verse, Kanye distorts, chops, or screws each passing couplet, panning each to opposite speakers, to portray the many torturous voices of a cuckold battling remorse and malice at once. And at next part of the song, when you thought you’d heard every surprise imaginable, Chris Rock begins a soliloquy, playing the part of a home-wrecker that West can overhear through a butt dial from his partner. Profoundly hilarious as it is, it’s still impossible to separate from West’s vivid nightmare.

‘Lost In The World’ is a multi-movement album closer that contends as a song as epic as ‘Bohemian Rhapsody,’ with its biomass of vocalists chanting the chorus before a Taiko drum breakdown. I mentioned earlier the way West sprinkled new production elements on previously heard songs – a version of ‘Lost In The World’ was leaked, but on the album version, there’s a point where the drums stop, Kanye’s voice leads the chorus for the first time, and a vocoded death-rattle takes over the mix like some orphaned android joining the choir of lost humanity. It’s as if he made the leaked tracks into a platform for an even greater listening experience, Trojan horses with which to jolt fans with joy when they heard the final versions.

The album ends with a full interpolation of Gil-Scott Heron’s ‘Comment No. 1’, an examination of American lies and the Black experience. It ends with the closing comment, “Who will survive in America?” repeated several times. Journalist Sean Fennessey interpreted this collaging as "a too-serious denouement for an album that is more about the self’s little nightmares than some aching societal rejection." And I call his interpretation a shamefully unimaginative white man denying that a black man’s nightmares of the self might have a little something to do with race. He must not have decoded the nuances of the black experience in ‘All Of The Lights,’ or heard a single line of ‘Gorgeous’.

But Fennessey’s most lamentable mistake is his failure to link Heron’s words with the song’s own verse by Kanye. Its standout line, “Let’s break out of this fake-ass party, turn it into a classic night” is a rejection of all status quo, a revitalization of love in a world of lust, a lone plunge into the unknown in search of the truth. No to the idea that hip hop is an ephemeral genre. No to award shows pitting artists against one another. No to any of societal expectation that feels like control. Ask yourself if West’s career would be at such risk at this time if he were white, or if Taylor Swift weren’t. Does Heron’s passage still not seem to fit?

The argument for My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy as the best album of all time usually begins with Pitchfork’s oh-so-rare 10.0 score, but the majority of fans that share the belief don’t even read the site. Maybe it’s the production, that features every instrument from cellos to Taiko drums, and blends every genre from electronic to classical while cementing hip hop as a timeless pillar of Western expression. It is such an endlessly layered Gesamtkunstwerk that I have no idea how it came together in just two years, and I imagine Kanye doesn’t either.

Maybe it’s the themes, that equally navigate power, fame, legacy, fear, love, loss, heartbreak, greed, lust, race, inequality, forgiveness, faith, truth, regret, redemption… is there any other facet of the human condition I might be missing? But like any classic album, it’s also the story, the cultural context, and the era-defining performances surrounding it.

Every hero has a hubris, and for Kanye that hubris is the certainty that he can achieve anything the rest of the world deems impossible. It’s what drove him to support the most pernicious president in history and bully a teenager on national TV, and it’s also what made him one of the world’s leading fashion designers after making some of the best albums of all time.

If you were one of the millions who just didn’t care for him, decrying his character for the Swift incident or the recent Trump supporting, I won’t try to convert you. You just need to know that there are millions coming from another side: the kids with no one to sit with at lunchtime, keeping someone in their headphones that reminded them there was always something left to believe in, even if no one else did. The rapper that recorded his first hit with his fucking jaw wired shut.

To me, this is exactly why West decided to leave in the meager applause at the end of the Heron sample as the last sound of the album—the most grandiose, intricately produced, emotionally pure album one man could make, closed with the sound of a tepid reaction. West is one of the most famously attention-obsessed figures in all of culture, but with this album, he became so certain of its quality, so attuned to his inner beauty, that he lost all concern for whether anyone would react or care at all. I can only hope that today, in light of his recent crises of self-worth – from psychiatric ward visits to publicly begging Drake for mercy – that he can look back on this time of his life, when he didn’t need anyone’s approval but his own to fulfill his fantasy.