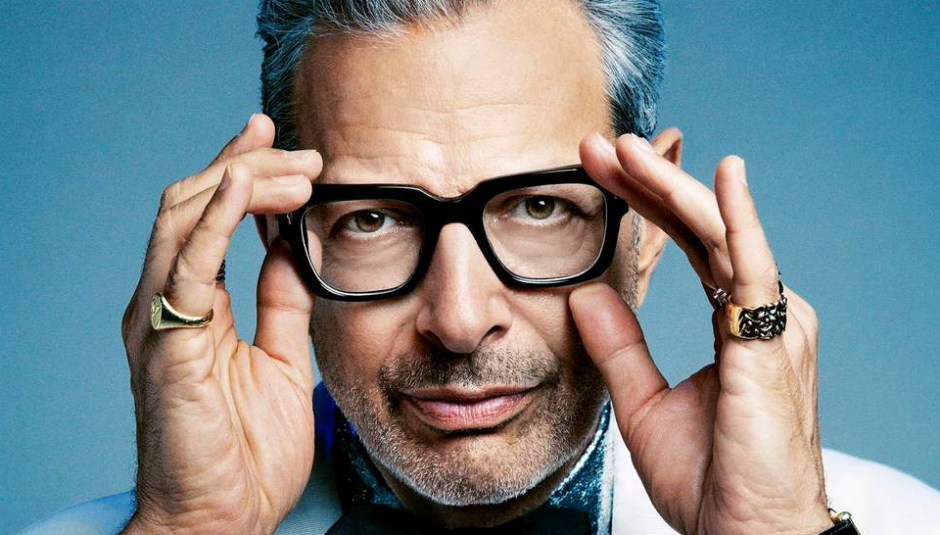

An audience with Jeff Goldblum is not like other interviews. For a start, there’s his innate Jeff Goldbluminess, an easy charm and earnest enthusiasm that’s impossible not to warm to. He’s possessed of a puppyish sense of curiosity, chasing his own thoughts off on tangents, occasionally taking off his glasses and staring into the distance. He deflects questions back, and often ends answers with an inquisitive “What do you think of that?” or “How does that sound?” Think less Hollywood A-lister, more wise old sage.

Then there’s his self-effacing, “aw, shucks” humbleness, a genuine gratitude that anyone cares about his foray into jazz (“Thank you so much for doing this,” he says after we speak. “It’s been so nice.”). He apologizes profusely for eating lunch during the interview and despite being tired and on a tight schedule, is unfailingly polite and gracious. Above all, you’re left with the sense that he’s not playing a role or curating a public persona – the real Jeff Goldblum is exactly how you imagine him to be, a man constantly amazed and inspired by the fact that he gets to be Jeff Goldblum.

We meet at the Corinthia Hotel, a monied, discreet establishment just off Whitehall; the lobby is dominated by a magnificent Steinway that, sadly, he doesn’t have time to play. He’s in London for one last round of promotion for The Capital Studios Sessions and a doubleheader at Ronnie Scott’s, part of the EFG London Jazz Festival and the last leg of a short, European tour. Paris and Berlin were also on the schedule, as well as the opening show at Cadogan Hall one week ago - “just a little jaunt,” he says. In true Jeff Goldblum style, he flew in this morning on EasyJet; no entourage, no airs and graces, just a custom Prada shirt and that million-watt smile. Of course he posed for a picture with the cabin crew.

By now you’re no doubt familiar with the story of how the young Jeff Goldblum fell in love with jazz. If you’re not, in short; he grew up in Pittsburgh with his radio worker mother, doctor father, three siblings, and a Steinway grand piano. At his parents’ insistence, he took lessons, which he initially hated. The turning point came when he heard one song – ‘Alley Cat’ – and resolved to learn it. From there he moved on to chord sheets for songs from the Great American Songbook, taking inspiration from the city’s own piano jazz star, Erroll Garner, and by 14 was cheekily phoning round local bars, saying he’d heard they were looking for a pianist. He got several gigs.

But why jazz? “It’s just mysterious,” he says. “When I was a kid, something in my bones was already a little like [rocks shoulders rhythmically, almost slinkily], you know? I just had that. That doesn’t mean I would have necessarily inevitably done anything with it of course, but I took piano.” He confesses to being “undisciplined” when it came to tutelage, but he had “a little facility for it – I was getting through my lessons.” More alluring were the records his dad and older brother would bring home; Erroll Garner Plays Misty, Sketches Of Spain, Stan Getz, and Astrud Gilberto. Then came ‘Alley Cat’ and he was hooked. “I just liked it, and that was that; I was off and running,” he says. He’s been playing almost daily ever since.

Despite this passion, he never wanted to make a career of it. “I was dead set on being an actor, but I just loved playing,” he says. “I kept it around when I was in New York, and then put it in some movies and plays; snuck little bits of it in here and there. Then thirty years ago I started to play out and about.” He’s had a Wednesday night residency at LA’s Rockwell Club for the last seven years or so, but it was an appearance on The Graham Norton Show last October, when he played with Gregory Porter, that brought his musicianship to the wider British public.

One of those watching was Decca’s head of A&R, Tom Lewis. Duly impressed, he flew to LA, watched a show, and signed him for an album. Lewis put Goldblum together with Larry Klein, the Grammy-winning producer, who in turn brought Till Brönner, Imelda May, and Hayley Reinhart on board. To recreate the free-flowing fun and laid-back lounge vibe of his Rockwell shows, a decision was made to recreate the club at the legendary Capitol Studios and record live in front of an audience; the result is a blast, like listening in to Golden Age Hollywood cabaret in someone’s living room.

But it’s serious jazz too; The Capital Studios Sessions opens with ‘Cataloupe Island’ and covers Nat King Cole, Charlie Mingus, and Duke Ellington. There are also songs by Nina Simone and Marvin Gaye. Was it easy choosing what to include? “The guys I’ve played with always wanted to play substantial, interesting jazz for them. I was interested in that too, and so we started to play with more focus; Thelonious Monk and Charles Mingus, Charlie Parker, Miles Davies and Sonny Rollins, Duke Ellington and stuff like that. When Larry saw our show at the Rockwell, he said: ‘I like what you guys are doing, especially because you make it accessible to people who haven’t necessarily been fluent in or introduced to jazz before.’ So some were songs that we’d been playing regularly.”

It was, says Goldblum, something of a group effort. “We started to work with Hayley [Reinhart] and got those couple of songs from her, and with Imelda [May], we fashioned what would be best for that, but those were his [Klein] and their ideas. Sarah Silverman and I had done that song before, so he liked that, and we just kept collaborating and fooling around; Larry, me and [musical director] John Mastro.”

Turns out Herbie Hancock – “my friend,” says Goldblum modestly – almost played with them, but it didn’t work out. Still, he encouraged them to do ‘Cataloupe Island’, and also suggested the Marvin Gaye song ‘Don’t Mess With Mr. T’. A few other classics didn’t make the final cut - ‘Epistrophy’ and ‘Bye-Ya’ by Thelonius Monk, and Sonny Rollins’ ‘Doxy’ – but Goldblum is more than happy with how it turned out. “It captured the fun and sexy kind of romance and sociability that was jazz back when it was popular music, you know?”

Jazz, especially in the UK, is enjoying something of a renaissance – the New British Invasion said Rolling Stone back in March. A colleague of mine recently asserted that the “punk rock spirit isn’t dead, it just entered the host body of jazz”, and listening to the fervent politics and innovation of Sons Of Kemet, or Kamasi Washington’s sprawling, concept-heavy musical arcs, it’s hard to disagree. Even cult indie heroes are dabbling, while a new generation of jazz maestros – the likes of Ryan Porter, Marike van Dijk, and Makaya McCraven – are pushing boundaries and re-shaping what modern jazz can be.

“Primally beautiful and stimulating stuff,” he says of jazz’s enduring appeal. “We noticed at Roughtrade the other day – we played a nice little concert – they were saying: ‘Look, there’s a whole young bunch of people here.’ Jazz was originally a popular music, and in my experience, there's something about jazz that hit me where I lived and breathed and pulsated [it]. It cycles back around and is true for other people, maybe that’s the cause.”

He goes on. “Jazz covers a lot of ground, and all sorts of different people can find some different things…live variations of what they may like, then they can certainly find real musicianship and virtuoso renditions of many things, which is not present in the same way in, let’s say, some other kinds of music.”

Meaning, you can’t fake jazz? “Yeah. I think so. I mean, past the entry level, you know? You start to have to be a little knowledgeable, and then you can find people all over whose devotion to it – life-long devotion to it – and serious investigation of it allow them to do something that, if you are receptive, is mind-blowing and soul expanding.”

Many trace this newfound mainstream enthusiasm for jazz to the release of La La Land in 2016, a film about a young jazz traditionalist’s desire to save the genre by returning it to its roots. Initially lauded as a delightful vestige of Hollywood musicals, the backlash was swift and brutal: “Clueless about what is actually happening in jazz” said Vulture; “A muddle of clichés” said Slate. The “whitesplaining” aspect was even more troubling; jazz is a uniquely black American genre, and as Ira Madison III put it, “if you’re gonna make a film about an artist staying true to the roots of jazz against the odds and against modern reinventions of the genre, you’d think that artist would be black.”

Goldblum’s wife, Emilie Livingston, was a body double for Emma Stone’s aerial stunts, and I ask what he made of the film and the resulting criticism. “I enjoyed it, I enjoyed it a lot,” he says. “But I don’t know that I read much or was very aware of the criticisms.” Really? I run through the gist of it and the main objections commentators had. “Well, I’d have to think about that,” he says after a pause. “It’s sensitive, the question of diversity.”

“To phrase it like that, being ‘saved’, doesn’t sound like it would be my favourite way to put it…the thing that would attract my seedling thinking, I would say, is that interested fans and students – and historians – might be led to what has gone before us. I don’t know about this ‘museum’ business, but a study of what has been accomplished and what has been around doesn’t sound like an unhealthy thing to me.”

“I would also say that it shouldn’t be adhered to rigidly in its current investigation. It should show that jazz is a lively, living, breathing, ever-evolving organism; just like we are and just like culture is. I would say it should continue to grow and be part of the current conversation." He pauses. "How does that sound?”

A show by Jeff Goldblum is not like other shows. For a start, he’s his own warm-up man. As we take our seats at Ronnie Scott’s, thirty minutes before he’s due on, Goldblum is already prowling between tables with a microphone, amusing and delighting the growing crowd. Part comedy, part light entertainment, he works the room like an expert, dropping witty bon mots and telling anecdotes. Just before showtime he casually says that if anyone wants a photo, just come on up; a queue quickly forms, and he poses for the last few seated at his piano after the band have already started playing.

Even between songs there are word games and quizzes, Mastro handing Goldblum a sheet of paper containing some fun diversion. “I read it cold, having never seen it; it’s a game I play with him,” he explains. So we get a Name The Movie From the Tagline quiz, Famous Shakespeare Soliloquys, and a hilarious segment where he has the audience teach him cockney rhyming slang. “I’m naturally yacky,” he says. “So I don’t mind extemporizing and otherwise shooting the breeze, off the cuff, from the hip, as it were. Audiences seem to get a kick out of it too.”

It’s not what people might expect from a show I say, especially not one by a Hollywood superstar. “It just kind of happened that way, organically. It really has evolved out of not trying to affect any kind of theatrical or entertainment aim, other than my own leanings. I know that when I go out and party, part of the fun for me is that my interest is following my curiosity about the interesting people that show up, you know? I don’t feel like we are stuck in anything; it just feels like a natural kind of way to proceed.”

“I do like to play games anyway. These days, we kind of work it. I don’t like to know anything about what we’re doing, so when I say that the whole thing is generally not strategic, over the long arc, it’s also not that way any one night. I don’t know what’s coming next and these nights are interesting to me partly because, just as much as the audience, it’s a surprising experience for me. It balances my disciplined way of playing every day, and I get the biggest kick from that.”

The shows may be a “let the chips fall where they may” event, as he puts it, but musically he and the band – the Mildred Snitzer Orchestra – are astoundingly good. He claims to not know the setlist in advance – “I don’t know what we’re going to play; I’m surprised to see if I can recognise their varied and sometimes tricky version of something” – but it doesn’t show; everything is razor sharp and tight, and flows beautifully. Goldblum isn’t really a soloist or virtuoso, but he really can play. He can sing too – on the record, his duet with Silverman is polished and sassy – although sadly, we don’t get much of that tonight.

Musically, the idea of improvisation – the back and forth of different solos, not quite knowing what anyone is going to do next – is something that he finds “ever-fascinating”, and you get the sense that he’s a little in awe of the talent he’s surrounded himself with. “There is always something life-relevant of being part of the conversation – in this case, the musical conversation – between human beings that is by necessity present. It causes them, while they are doing it, to pay particular attention to each other, and be inventive and creative on the spot, as they are making it and as you are listening to it. That’s pretty good, and it overlaps in my life in my acting interests, in my life interests and, you know, just daily interactions and navigating this world.”

Ah, yes. Acting. Goldblum’s day job, and the source of his enduring appeal. His scene-stealing turns are numerous, yet his most famous roles – most notably in The Fly and Jurassic Park – continue to define him; witness the crowds who flocked to see 25-foot statue of Goldblum as Dr. Ian Malcolm that appeared next to Tower Bridge in July. He takes such adoration in good grace, and says he enjoyed his minor role in the latest Jurassic Park film. “The original movie is celebrated here and there, and I’m currently still myself enjoying the kind of…maybe even future opportunities to investigate that character; it’s not uninteresting to me.”

Future opportunities? Meaning, Dr. Ian Malcolm will grace the big screen once again? “There’s no news about the fact that they are writing another one because that’s already out and about; I think Colin Trevorrow and Steven Spielberg and the producers planned this current Jurassic World to be a trilogy. He [Trevorrow] is a smart guy, and I’m gonna see him tomorrow as a matter of fact because he’s here. So there’s nothing new, except that there is the seed of an idea and some talk going on, and that’s all I can say about that.”

For now though, he’s focused on jazz and the band, and what comes next. The whole experience has been “kind of a blast; it has really been fun.” Fun enough to do again? “My general approach and credo – blueprint at this point – is I want to do things that are fun and exciting, and work with people that I’ve enjoyed being with and am excited about. I’m having a fertile cycle of acting, but going with the band to places here and there, outside the Rockwell, has been great. I’m doing things that I like to do, and I’m liking doing this. So [another record] could be fun.”

At the end of the show, there’s a seemingly never-ending line of people wanting to shake his hand, say a few words, or snap one more selfie. With the patience of a saint, he greets them all, posing, chatting, and generally just being the best Jeff Goldblum he can be. No one leaves disappointed.

“I thank my lucky stars and my Mum every day for introducing me to this, and that I’ve had a chance to have a life in music, because my day is really changed. I can’t pass a piano without wanting to sit down, and being able to spend time by myself, with such pleasure, is just fun.”

Jeff Goldblum the jazz player. What do you think about that?

The Capitol Studio Sessions is out now via Decca Records. For more information about Jeff Goldblum and his jazz odyssey, please click here.