There’s a bit in Mark Kermode’s excellent musical memoir, How Does It Feel? where he and his bandmate, Simon Blair, decide to drive to the BBC and hand a demo tape of their new band, Brag!, into the hands of a top Radio 1 DJ. Any will do. Surely a move that will kickstart an inevitable journey to Top of the Pops and the musical big leagues. They arrive toward the end of David ‘Kid’ Jensen’s evening show, tell the receptionist they have an appointment and wait it out in the foyer, assuming the DJ would have to emerge soon. After an hour the pair of teenagers are still there, being eyed suspiciously by a security guard, the unknowing Jenson yet to emerge.

35 or so years later history is repeating, only this time Kermode is playing the role of Kid Jenson, and I’m playing the role of BBC imposter. I’m supposed to be sitting in on the Radio 5 Live film review show Kermode has hosted with Simon Mayo for over a decade; unfortunately, the receptionist at the BBC’s Wogan House, where I’ve been told to arrive, has never heard of me. Or Mark Kermode. Or the show. I notice some pre-prepared security passes on her desk, so I toy with the idea of posing as someone else, just to make it past the gatekeeper. My eyes do a surreptitious downward flick, searching for a name I could borrow. The pass at the top of the pile says “Rod Stewart”. I consider it briefly, but decide I don’t have the charisma to pull it off.

It’s perfect, because taking ridiculous chances and somehow getting away with them is a key theme of Kermode’s new book. How Does It Feel? is an entertaining read by anyone’s standards, but if you’ve ever been in a band, if you understand the idea of throwing yourself body and soul into making music with the absolute surety that what you’re doing amounts to genius, even – and especially – when it definitely, definitely doesn’t, then it’s a book you’re going to adore.

“I think anyone who’s been in bands shares those experiences”, the critic, broadcaster and, yes, musician tells me over coffee. “Certainly things like organising a gig just so you can support the lead act, whether they want you to or not, are very common. The first person I showed the book to outside the publishers was Johnny Greenwood, because I wanted to make sure from a musicians point of view that it held water. He said it was written by someone who clearly had a passionate enthusiasm for making music, which is really lovely because he is a proper musician’s musician and if he thinks that, it’s probably true.” Who are we to argue with the Oscar-nominated guitarist from Radiohead? “The thing I wondered,” he continues “was would it make sense if you hadn't been in bands? I've spoken to a lot to people who haven't and they seem to get it”.

It’s not a huge surprise that the book translates beyond musos and both wannabe and actual rock stars – after all, Kermode makes a living making the unpalatable enthralling. He’s one of the country’s best-known film critics, possibly the best known, yet his taste in movies is far from mainstream. He’s a gorehound and horror obsessive, and while he’s happy to take the occasional holiday in the multiplex, he’s usually more excited about tiny-budget art-house fair. Despite this, his radio audience is huge and his podcast with Mayo is rarely out of the top ten of its iTunes category.

Back at the BBC, I perch awkwardly on a bin in a control room resembling the bridge of the Enterprise, having been rescued from foyer purgatory by “Producer Simon” (Kermode’s life is thick with Simons. There are at least three in his book). Emails and texts from the audience flood in, and the affection, constant in-jokes and earnest requests to read out marriage proposals are as warm as they are unending, though a little at odds with a personality who can talk your ear off about the grizzly sound design of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and probably its sequels. It’s easily explained: At his heart, and despite his protestations of being “just a critic”, Kermode is a storyteller and whether that story is about how James Corden's performance in Peter Rabbit is among the worst crimes yet committed by cinematic artistry, or how he formed a punk band with David Baddiel (“yes, that David Baddiel”) at school, he has a way of translating it into a universal language of warmth and wit.

This is Kermode’s fourth memoir, but the first to deviate from his primary gig as “the nation’s most trusted” film critic. In a way it can be seen as a companion to his 2010 book, It’s Only A Movie, but where that work told the story of a life watching film, this tells a parallel tale of post-punk, chancing it, and skiffle. It’s actually the story he wanted to tell first. “I've been trying to write it forever”, he says. “Back in 2008, my editor at the Observer asked if I could write about something other than film, and I said ‘but that's what I write about: film’ and they said…” – here he gives his Observer editor an exasperated tone she almost certainly didn’t use, because as discussed, Kermode is a yarn-spinner and anecdotalist before anything else… - “‘Yes but could you write something else?'. So I wrote this piece about playing in bands and the history of skiffle. I really enjoyed writing it and thought I could turn it into a book. I went to a publisher and said: 'I really want to write a book about being in bands' and they said: 'You're a film critic. Can't you write a book about film instead?' So I did It's Only A Movie, and that did quite well, so they said: 'Could you write another film book?' I said: 'I really want to write a book about bands' and they told me: 'People want to read you on films'. I kept being told that.”

It was a chance meeting with a different publisher that finally gave him the opportunity. “I was talking to Jenny Lord, the editor of the Movie Doctors book I did with Simon Mayo”, he tells me. “We got on really well and one day I was sitting down with her, telling her how I'd been trying to write this book about pop music and movies, like a history of pop in the movies, and I was really struggling with it, and the reason was that as soon as I sat and started writing about the history of pop in the movies it started turning into this thing about building an electric guitar when I was a kid. It turns out her brother was somebody who’s really, really obsessive about details of guitars and she'd grown up around the detritus of guitar parts. She asked for a sample chapter, I sent it to her, and she said: ‘Okay, we’ll publish it’. It was the thing I'd always wanted to write, and I really enjoyed writing it. I had to get it out of my system. I couldn't do another book until I’d gotten it out of the way.”

Film may be Kermode’s professional preoccupation, but if you ever meet him it doesn’t take long to get onto the subject of music. When I interviewed him for his 2014 book, Hatchet Job it was a struggle to keep the conversation on the subject at hand because somehow, inevitably, we wandered on to the history of skiffle and the fact he had once built an electric guitar. Music has always been part of Kermode’s life, from bashing pots and pans with his brother as a child, to a series of “unlistenable” post-punk bands in the 80s; from performing Morrissey’s ‘Suedehead’ with his skiffle band, The Railtown Bottlers, with Suggs on TV in the 90s, to cutting an album at the legendary Sun Studios, where Elvis got his start, with his group the Dodge Brothers in 2013. Last year it led to playing chromatic harmonica onstage with an orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall despite, crucially, not really being able to play the chromatic harmonica.

These days traditional rockabilly, in both its English and American flavours, dominates Kermode’s musical landscape but just as Jaws isn’t really about a shark, How Does It Feel? isn’t really about skiffle. It’s about learning an instrument for the sheer joy of doing it. About recording in your favourite studio or supporting your favourite band just to see if you can pull it off. It’s about wish fulfillment, awkward moments, and the power of sound. In short, it’s a book about really, really loving music: playing it, discussing it, hearing it; something that its author has done for as long as he can remember.

He traces the beginning of music as an obsession to 1973 when, at ten years old, he heard The Rubettes’ pop confection ‘Sugar Baby Love’ for the first time, describing being “pinned to the sofa” by the sound of it. “I think I still get that now. It has the most brilliant opening,” he explains, an explanation that inevitably descends into a thorough rundown of how the song came to be recorded – which I’ll skip to avoid stretching my word-count into that of a short novel. Trivia-aside, that thrill has never left him. “I remember there was a documentary about the Beach Boys where Brian Wilson said he was driving along in America and something like ‘Be My Baby’ came on and he was so astonished by it he had to pull the car over,” he says. “Everyone's got that moment. That was it for me.” From there he graduated to the glitter rock of Slade, Sweet, and David Bowie, acts he still loves. Seeing Doctor Feelgood at Hammersmith Odeon gave him a taste for meatier live rock, and Bowie’s graduation from glam-pop to arty oddball led him to more serious fare. From there it was onto cerebral post-punk, Television, Yachts, and his beloved Comsat Angels (“the band Joy Division could have been if they could sing and write songs”).

Kermode’s first forays into forming bands, both at school in Hertfordshire and at University in Manchester, were all in noisy post-punk. “Isn't it weird that there were so many of us in that period making music that was almost deliberately unlistenable?” he says of the early eighties. “The era of Television and Gang of Four, stuff that was meant to make you wince a little bit. You wanted people to listen, but it felt like selling out if you wrote verse-chorus-verse-chorus-middle eight-chorus. You had to deconstruct it all the time. It's really peculiar. If you ever had a bit in a song that was catchy you'd automatically have to destroy it and put it back to front.” It’s no wonder that Johnny Greenwood, who tried to sabotage Radiohead’s ‘Creep’ with a slash of unpalatable distortion, is a fan of the book.

At university, despite studying English, making music appears to have become almost all-consuming. Kermode describes Hulme in Manchester, where he spent much of his student life, as “like some massive creche for bands – wherever you went there was a recording studio, there was a band. You were right in the middle of it. Manchester was, and still is, really vibrant, but in that period anyone could be in a band, and everyone was usually in two or three at the same time.”

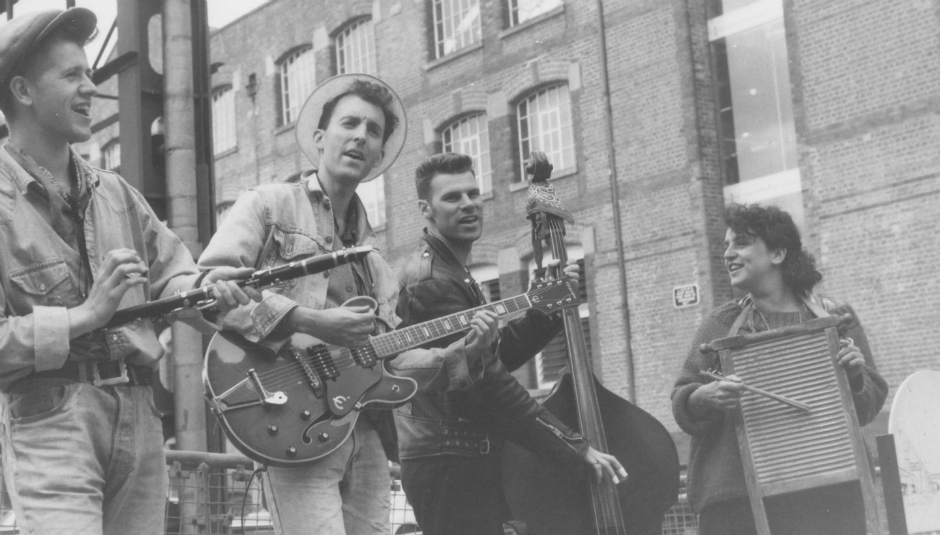

Unlike many of his peers, though, Kermode didn’t leave his performing career behind when he graduated. While helping provide the music for a play called The Death of Joe Hill at the Edinburgh Fringe, he and castmates Olly Fox and John Preston fell in with washboard-player Alison Armstrong-Lee and guitarist Matt O’Casey to busk old skiffle tunes, discovering they could make a packet on the streets. The band, which they christened The Railtown Bottlers, was soon enriched when Kermode forked out £50 for a double bass, partly because it looked cool and partly because he figured he’d struggle to break strings at the rate he did as a guitarist. He was right, though he did develop a habit of playing so hard he’d snap the neck clean off, and took to carrying wood glue to gigs. The Bottlers established a name for themselves on the street circuit of the 80s and 90s, eventually winning the International Street Performers of the Year award in 1991, leading to numerous TV appearances and a gig as the house band on Danny Baker’s BBC One chat show.

Roots music, skiffle, and rockabilly were always in the background of his life. As a kid, he loved Elvis movies, though he later realised the schmaltzy soundtracks of the King’s 60s film career barely counted as rock & roll. Still, the seeds were sown and “rocking” became a part of his identity. For starters the rockabilly look has never been far away: He’s been sporting a flat-top quiff since the early 80s, and the cover of How Does It Feel features a very young Kermode decked out in an old Ted suit, bootlace tie, and quiff, a look he adopted for his short-lived lefty musical-comedy persona, Henry One Hundred (an act he point-blank refuses to bring back for any amount of money, ever). His BBC pass still has him frozen in time in the 90s, with an immaculate, jet-black pomp do.

“Where I was, in North London, there was quite a big rocking scene,” he says of his childhood. “There was the Southgate Royalty where bands like Matchbox, who were old Teds even back then, would play. I never thought about skiffle until we got up to Edinburgh to do the Death of Joe Hill and Matt and Al turned up.” He soon caught the skiffle bug, realising it intersected neatly with a music and an ethos he’d loved his whole life. “When we were busking we were playing things like 'This Train', but we'd do it in a rockabilly style,” he explains, “and skiffle, rockabilly and blues, they're very close together. It's all blues, really. It was only later that I realised I'd grown up in a house where my dad played [blues legend] Jelly Roll Morton all the time, that sort of barrelhouse blues stuff, and he was really interested in what's now referred to as trad-jazz, very early recordings of very raw stuff, which again is very similar to jugband and skiffle music. I think it's the rawness of it [that attracts me]; not overcomplicating things. I never really liked prog, I was never into the layers and layers of synthesizers, I liked the idea of something that was simple, even if it was simple and different. If you listen to Marquee Moon all of the guitar riffs are really complicated and difficult, but the song structures are actually quite straightforward: Beginning, verse, middle bit.”

For someone who once considered such a structure as “selling out”, going backwards in time musically was also growing up. “Around ‘82, ‘83 my interest in newer bands started to fall apart and I started to listen to older and older music,” he says. “By the time I left Manchester, I had no idea what was going on with modern music at all.” Part of what appealed to Kermode about skiffle was the same thing that appealed to him about punk. “Billy Bragg said that skiffle is proto-punk,” he says, “three chords and the truth. And it is, he was right.”

At the BBC Mayo and Kermode’s show is coming to an end for this week. With impressive, clockwork timing Mayo throws to his partner to announce the movie of the week, cutting across him in mid-flow, his higher voice neatly slicing through Kermode’s slightly bassier tone as the two parry and dance and then stop just in time for the news. It’s a combination of timing, improvisation, trust and structure that feels almost musical. It may sound conceited, but seeing it unfold in front of you, you realise Kermode the musician and Kermode the broadcaster are two personas never especially far apart. After the show, he’ll jump on the back of a waiting motorcycle and zip across London to catch a train down to Southampton, where he has a gig with his current band, the more Americana-influenced Dodge Brothers. It’s an exit that is, appropriately enough, pretty rock and roll.

How Does It Feel? is out now on Orion Books. For more information about The Dodge Brothers, please visit their official website, and for information about Mark Kermode's various projects and forthcoming book tour, please click here.