There can be very few times in pop music history where a band’s music sounded so suddenly heartbroken in the wake of the success they’d always dreamed of. But Manic Street Preachers have never been an ordinary band, and the Manics of 1998 were in exceptional circumstances indeed. Barely three years had passed since the disappearance of guitarist and lyricist Richey Edwards, a case still unsolved 20 years later. The band had bounced back stronger than anyone would ever have expected: in ‘A Design For Life’ they’d released one of the great singles of the 90s, with ‘Australia’ they’d guaranteed themselves royalties from Match of the Day for the rest of their lives, and with 1996’s Everything Must Go they had achieved a proper landmark rock album; A record so ubiquitous it was once used on BBC school drama Grange Hill to literally mark the passage of time. Few bands get penetration on that level, particularly when they’d opened their previous album with a lyric about “dumb cunts”. Everything Must Go bagged the group BRIT Awards for Best British band and album, dedicated by bassist Nicky Wire to “every Comprehensive school in Britain”, which makes sense given the Grange Hill thing. That era of the band was capped by a triumphant headline set at the 1997 Reading Festival, the weirdo-intellectual glam-punks form Wales were level pegging with Radiohead, Blur and Oasis for the title of ‘biggest band in Britain’, something which they’d boasted would happen back in 1990, but few had actually expected.

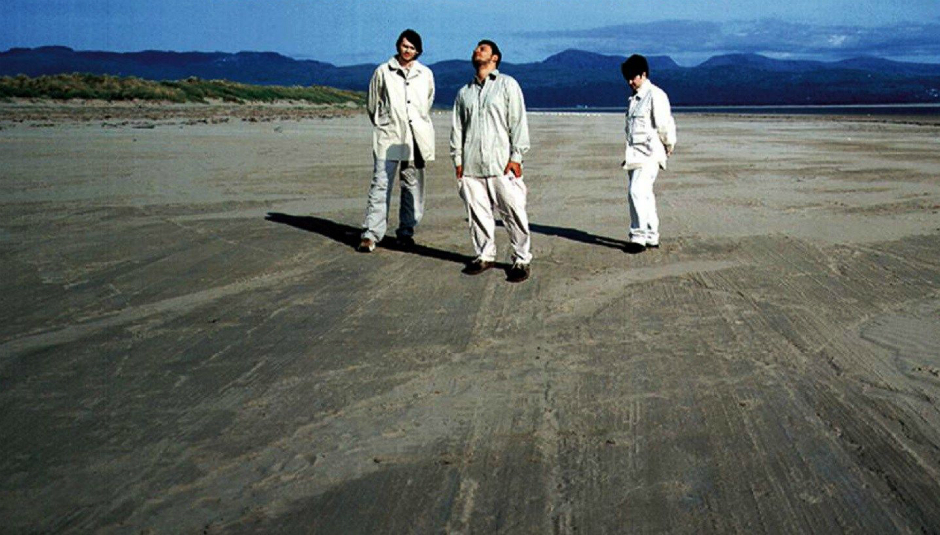

Which is all well and good, unless you happened to be in the Manic Street Preachers who had to work out what to do next. Everything Must Go, despite the tragedy that preceded it, seems to have been a relatively easy album to make. Musically the band had kicked against 1994’s nihilistic landmark The Holy Bible with an album that breathed and expanded, full of songs that suited Rugby club singalongs, jukeboxes, and teenage bedrooms alike. Everything Must Go was also very much an album by the four-piece version of the band, using songs and lyrics written prior to Edwards disappearance. He even turns up on guitar on ‘No Surface All Feeling’, making it pretty unique among Manics albums. Now the cycle was done the remaining trio were truly on their own. A still-grieving Nicky Wire, tasked with writing an entire album from scratch for the first time, found himself weighed down with writer’s block and depression, eventually turning in a selection of lyrics that while rich and multifaceted, were inward-looking, thoughtful and downbeat even by Manic Street Preachers standards. Guitarist and singer James Dean Bradfield and drummer Sean Moore responded with music that was stranger and dreamier than anything in their canon, and by slowing everything down considerably.

‘If You Tolerate This Then Your Children Will Be Next’ debuted on Jo Wiley’s Radio One show on a hot July morning in 1998. Fans poised with their fingers on their play/record buttons found themselves listening to something far odder than any Manics single that preceded it. ‘Tolerate…’ triples-up as a song about the Spanish civil war, Wire’s insecurities, and stubborn Welsh pride, its glacial pace and blend of arena-rock (the solo, the “woaaaaah’s”) and electronic washes casts an atmospheric and vaguely disconcerting spell, subtly driven by a pumping, almost-Motownish bassline. You knew where you were with ‘Kevin Carter’. This was something else. The single went straight in at number one, which is pretty remarkable when you consider how weird it is, something only a band at the peak of their popularist powers could manage.

‘...Tolerate’ was a good indication of what would follow. Released in September of 1998 This Is My Truth, Tell Me Yours was a richly textured, melancholy and troubled masterpiece, a billion miles away from the brash rock of early albums Generation Terrorists(1992) and Gold Against The Soul(1993), though it shared a mournful focus with The Holy Bible, and an occasional wide-screen accessibility with Everything Must Go, the latter thanks to returning producers Mike Hedges and Dave Eringa. It’s an album about growing older, no-longer knowing where your place in the world is, not really seeing your younger-self in the mirror, trying to understand where you come from, what you’ve lost, what you’re left with and what you’re proud of. It has an astonishingly weary and reflective mood considering it was written by a band all under the age of 30.

Musically this is both the most soulful and the most interesting the Manics had ever been (and arguably would ever be, though 2013’s Rewind The Film comes close). Whereas the strings on Everything Must Go made it soar, on ‘The Everlasting’, bedded in a flat-sounding retro drum machine, they gently pull you down into the darkness. It sounds beautifully defeated. ‘Ready For Drowning’ joins ‘A Design For Life’ and ‘Motorcycle Emptiness’ as one of the most emotionally affecting things the Manics have ever done, cascades of fuzzy distortion, piano and rolling drums mirroring the literal flooded valley in Wire’s lyrics, with a beautiful organ melody providing something solid and tangible to hang on to as the waters rage. ‘I’m Not Working’ is the sound of bed-paralysis through tone poetry. Its ability to evoke the resignation of a depressive slump while sounding absolutely heartbreaking is perhaps the album’s most quietly impressive moment; making use of treated super-reverby drums and, of all things, electric sitar. ‘You’re Tender And You’re Tired’ takes notes from Bradfield’s beloved Motown ballads, while ‘My Little Empire’ allows a raindrop riff to slide down a gorgeous, lonely cello evoking Nirvana’s ‘Dumb’ and ‘Something In The Way’. A sighing backing vocal from Wire actually sounds sadder than the cello, and that takes some doing. ‘Born A Girl’ has one of Wire’s most nakedly brave and self-explanatory lyrics mirrored in Bradfield’s stripped-back guitar and a plaintive reed organ.

Even the upbeat numbers are suffused in sadness. When Bradfield introduced ‘Tsunami’ at the band’s landmark Millenium show, he dedicated it to their manager, Martin Hall, because “he likes the fast ones”. The thing is, on the record at least, ‘Tsunami’ really isn’t that fast. It’s a song struggling to break free of its shackles and rock out, played by a band determined not to let it. Bradfield creates a soaring hook out of the title (and the most literal bridge-part of all time in “Inbetween / Inbetween / Inbetween / INBETWEEEN!”) and a string section bussed in from the Everything Must Go sessions constantly tries to push the song to the rafters, but the heartbroken and grieving tone of This is My Truth… simply won’t let it fly. The tension works in its favour. ‘You Stole The Sun From My Heart’ is the most obvious hit on the whole album, and it's to the band’s credit that they waited until the third single to release it, presumably knowing had it been the lead track it would have massively outsold ‘...Tolerate’ but equally would have misrepresented the record to come. It’s the most straightforward rocker here, catchy to the point of irritating, but there’s no hiding Wire’s lyric, an ode to how being in a band just isn’t that much fun anymore. He gives the game away with the kicker line, one of his finest: “I have got to stop smiling”, sings Bradfield “it gives the wrong impression”.

If The Holy Bible dredged the darkest parts of Richey Edwards’ troubled soul, This Is My Truth does the same for Wire. It’s a suite of lyrics from a man emotionally and physically burned out, trying to take comfort in his homeland and routines and very obviously still bewildered by, and grieving for, his missing friend. What makes these lyrics special is the way the man known to his Mam as Nick Jones is able to cover such diverse subjects as fighting for what you believe in (‘Tolerate’), the sacrifice of a Welsh village to supply Liverpool with a reservoir (‘Ready For Drowning), mute twin sisters who ended up in Broadmoor (‘Tsunami’) and the Hillsborough Disaster (‘S.Y.M.M’) and make each one feel personal. An intertextual richness that only a very skilled poet can achieve.

This Is My Truth... was a commercial smash, bagging another round of awards and sales in the millions, headline slots at Glastonbury and V99, and leading to the band’s stadium triumph on New Year's Eve the following year. Still, many fans weren’t impressed, finding the record too morose and emotional. You can’t blame them – it’s an album with almost nothing in common with the snotty anthems of band’s earliest days, the tightly wound fury of The Holy Bible. You got the sense the band themselves started to agree; after the Millenium show Wire was heard to remark “thank fuck we’ll never have to play ‘The Everlasting’ again” (he was wrong). When they returned it was with the amps turned up and the spite at maximum. Manics history tends to see This Is My Truth…. as either the start of a decline or else a depressing blip. It’s a shame. This is a rich, unique and deeply special album that could only have been made by this band at that exact moment. It’s something they needed to do to survive. Twenty years on, it remains a powerful reminder of what they went through.