It’s pretty easy to look back all misty-eyed at New York circa 2001 as a wellspring of freshly minted bands come to save rock and roll. After all, that year proved to be the springboard for The Strokes, Interpol, Yeah Yeah Yeahs, TV On The Radio, LCD Soundsystem, and widened out from its NYC roots to include The National, Bright Eyes, and The White Stripes amongst countless others. This swathe of supposed independent bands breaking out into mainstream culture was met with levels of hyperbole not seen since the previous decade’s Britpop explosion. Rags like NME hit pay dirt in terms of cover stars with the skinny jean and leather jacket-clad Strokes, the rigorously colour co-ordinated White Stripes, and the sophisticatedly dour Interpol (with their last issue printed in 2000 sadly Melody Maker’s timing was unfortunate, to say the least). But given that collectively these bands caused such a stir throughout the early 2000s it’s curious that this ‘scene’ was never really named in any definitive way.

References to the era range wildly and are nothing if not vague: the new new-wave, post-punk/garage revival, the class of 2001, the return of alt-rock/guitar music blah blah blah. It’s unusual of the media not to galvanise such a scene, cementing its definability and therefore saleability like Britpop or grunge before it. But then, even fans of many of these band’s couldn’t refute their debt to the past perhaps like no other music movement before it. And it wasn’t just one genre or scene that was heavily referenced: The Strokes were indebted to the Ramones and Television, The White Stripes to 60s garage rock followed by Leadbelly for instance. Equally, these bands were emerging post-9/11 in a country whose foundations had been immeasurably shaken; everything seemed less easily definable, the world more confusing.

Whatever this nameless period was it all seemed to begin in 2001, the year that The Strokes - the undisputed poster boys for NYC’s burgeoning scene - released This Is It, and The White Stripes presented White Blood Cells. At the same time, another NYC band were also beginning to make waves with their self-titled EP. While The Stokes were urging us to meet them in the bathroom and the White Stripes were yearning to get married in a big cathedral by a priest, the Yeah Yeah Yeahs were crushing some poor soul with a nonchalantly delivered “As a fuck son, you sucked.”

YYYs were the most fun and the most abrasive of that era; heavier than The Strokes, and whereas they share the paired-back bass-less approach of the White Stripes, they were less blues influenced than their music was punk-informed. They shared a gothic aesthetic with Interpol, but with added flashes of Day-Glo colour and a wry sense of humour. And none of those bands were sexy like the Yeah Yeah Yeahs were. Their EP would prove to be a mere tease for the riot that was to come.

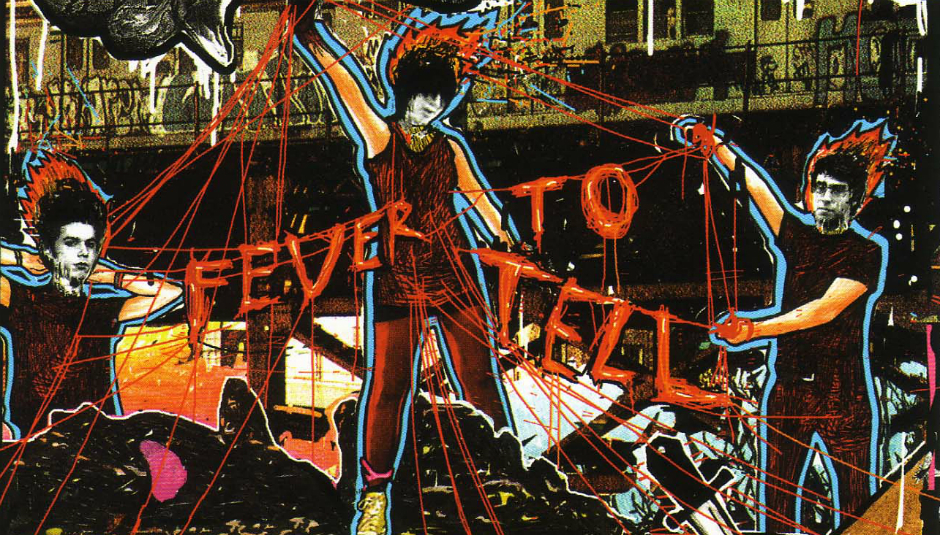

Just a couple of years later their full-length debut Fever To Tell was unleashed on the world in all its lawless, sordid glory. Even the cover art was a contrast to the clinically perfect sheen of This Is It or the monastically strict approach of The White Stripes. It was messy. A little ugly even. As it turned out the air of couldn’t-give-a-fuck obnoxiousness of the artwork extended to the music held within.

“I'm Rich / Like a hot noise / Rich, rich, rich / I’ll take you out, boy / So stuck up / I wish you'd stick it to me / Flesh ripped off.”

Thus opens Fever To Tell in unequivocally combative fashion. But musically ‘Rich’ merely dangles a carrot of sinewy garage-rock as tantaliser for the explosive tunes that will follow. The first two-thirds of the record maintains a relentless pace, barely allowing time to digest the various sonic assaults and curious lyricism. Fever To Tell is flooded with urgency, which the aptly titled ‘Tick’ observes with a flip from a lean shuffle to Karen O’s feverish delivery of "Tick tick tick tick tick tick tick tick / Time you take it, time you take it" all within a heartbeat. Given these songs are the product of just drums, guitar, and one vocal this bare-bones set-up musters one hell of a racket. The elasticity of Nick Zinner’s guitar playing and Brian Chase’s ripped yet minimal percussion paired with the ostensibly unpredictable force of Karen O’s performance makes Fever To Tell feel like the wheels might fall off at any moment.

Perhaps the best example of the electric hysteria they are so adept at creating is ‘Date With The Night', a two minute and thirty-five-second rollercoaster ride of Hitchcockian suspense. While Zinner’s scaling and descending circular guitar stand in for Barnard Hermann’s stings and Chase’s drums provide a bludgeoning backdrop, Karen O ramps up the drama with the violently repeated "Choke choke choke". Nearly 15 years since its release ‘DWTN’ remains an utterly thrilling listen; it stands as one of their finest moments and remains one of rock’s very best. It’s brutal, unrelenting and seriously sassy, but as with much of YYY’s output, it’s also a darkly danceable affair (‘Y Control’ also exemplifies the record's floor-filling capability, often in short supply in alt-rock music). This was an album that required more than pervasively dull pogoing or head banging, Fever To Tell demanded flailing limbs and extravagant shapes.

Lyrically the record is an absolute hoot that matches the mania of the music admirably. It’s pervaded by gothic touches that made YYYs feel more dangerous and exciting than many of their contemporaries. The bluesy ‘Black Tongue’ suggests "You can keep your black tongue / Well, I found it at the mortuary", hammer horror style, and ‘Man’ twists country tropes about hanging on to your fella with Karen O proudly confessing, "I gotta man that makes me wanna kill". Language and it’s common associations are consistently undermined and toyed with, and it often upends gendered vernacular: "Boy you just a stupid bitch / And girl you just a no good dick". Equally, YYYs often venture into taboo areas to mischievous and entertaining effect, flirting with incest a la Pixies - from ‘Black Tongue’s suggestive "We’re gonna keep it in the family" to ‘Cold Light’s pitch, "Yeah, we could do it to each other / We’re like a sister and a brother / Go go go go go!"

In lesser hands, these themes could fall flat, lose any sense of their inherent playfulness, and just feel a bit creepy. But Karen O is more than equipped to covey both the gag and the ferocity. To a certain extent, she shares her antagonistic snarl with Chrissie Hynde - particularly on Pretenders harsher tracks like ‘Precious’ (which includes the biting retort "Not me, baby / I'm too precious so fuck off!") Much like Hynde’s ability to flit between that aggression and the crushing tenderness of ‘Hymn to Her’ Karen O can arouse emotion with the best of them. 'Maps' was no doubt an entry point for many to the YYYs, in lieu of being enticed by the more abrasive tracks, and it would go on inspire countless indie-club singalongs and subsequent booze-fuelled blubbing. But despite being one of those songs that's been overused and overplayed, it retains its power as a simple, potent song that captures the quiet desperation and powerlessness of loss.

Fever To Tell is acerbic, aggressive and fucking noisy, but towards the end of the record, the band begins to surrender to romance. From the sleepy resignation of ‘Modern Romance’ ("It never lasts / This is no / There is no / Modern romance") to the hidden track (a charming tradition for which streaming was the death knell) ‘Poor Song,’ which offers a more hopeful riposte to the latter's incredulous sentiments. Fever To Tell achieves an equilibrium of cool-headed cruelness and gut-punch vulnerability.

YYYs managed to translate every ounce of the precarious balance of danger and tenderness live. I managed to catch them a number of times throughout the 2000s. Their 2004 headline show at Brixton was a bracing introduction to Karen O’s live prowess and extravagant wardrobe - in this instance a rainbow coloured leotard - and the United Sounds of ATP (for which they curated a day) was also triumphant. But it was perhaps their gig at ATP’s 10th birthday celebrations in 2009 that sticks. Even back then they seem to know the power of their debut, opting to perform Fever To Tell in its entirety over an It’s A Blitz heavy set, which had come out earlier that year.

“If you want to get on stage with the adrenaline of having just killed a man, then listen to the Birthday Party's Hee-Haw. Not everyone wants to hit the stage bloodthirsty but I personally like being in a crazed state before getting up there.”- Karen O

YYYs were really quite late that evening, and the inebriated crowd began to get grumpy, booing the band as they finally took the stage. We were duly greeted by way of Karen O screaming "YOU SONS OF BITCHES, WE JUST GOT HERE MOTHERFUCKERS!" before they burst ‘Rich’. It was mean, and we loved it. Their set was incendiary and demonstrated their continued commitment to visceral performances.

If it were possible to anthropomorphise sound YYYs would certainly nail it. Zinner’s wiry frame and shock of hair felt the perfect fit for his playing that could flit from steely to distorted in an instance; Chase’s unassuming and bespectacled appearance somehow matched his precise yet powerful beats, and as for Karen O, well, where to start? She might have been surrounded by lads - both in her own band and within the wider scene - but it was she that brought the most badassery to her performances both live and on record, in addition to a welcome dose of femininity. I saw The Strokes, The White Stripes, The National, Bright Eyes, amongst others at the time, but (aside from the heart-stopping excitement of witnessing the newly re-unite Pixies perform) it’s the YYYs gigs that remain indelibly etched into my otherwise withering memory.

There was, valid, criticism that a few of this era’s bands rested too heavily on their influences. Whereas some merely aped the great and the good before them, YYYs performed dark alchemy. You can plainly hear elements of Led Zeppelin, Souxie Sioux, and the Birthday Party to name a few, but as this band absorbed past masters they, in turn, spewed it all out in their own image.

The guitar-led music revival wouldn’t last. For a time America was the cooler cousin again (they got The Stokes, we got Libertines), but then it atrophied into beige MOR of the Killers and Kings Of Leon, much like grunge morphed into Bush and Nickleback. This nameless period never reached the dizzy heights of those scenes commercially - no doubt due to the changing landscape of music, which put paid to the old model. The industry no longer supports a system whereby bands record albums in a studio over time, the new way is far more conducive to homemade beats, which can be churned out with relatively little cost.

In that sense, the class of 2001 were probably the last of their kind. The final hurrah. But what was the scene's real value anyway? Did it push music on? Did it have to? Did this nameless beast ever really exist as some joyful homogenous movement? Who cares. Those few years produced some exceptional records among which Fever To Tell ranks as one, if not the, best. This type of music - whatever you want call it - has and still exists as it always will. There’s so much emphasis on its mainstream success, and of course you want to see the bands you love do well, but does that really define or impact on why you love them? The pot’s empty, time to return to a truly DIY method, which means putting in the legwork to find these bands and support them. The next great record is always around the corner.

Truth be told, listening to their debut does plant me straight back to those early post 9/11 years, and the glory days of ATP (before it all went tits up) pre-smartphones and smoking ban (shit, even that’s electronic now; I'm reduced to vaping furiously as I write this). But I also still relish it free of those associations, as with all great records it stands up independent of nostalgia’s crutches. To say it’s their definitive statement is no slight on their later work, as few bands ever produce a record as truly special as Fever to Tell. It rocks. Hard.