"The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom" William Blake

"The poet makes himself a seer by an immense, long, deliberate derangement of all the senses." Arthur Rimbaud

The philosophy of "live fast, die young" is deeply embedded in rock culture. The concept of rock stars dying at a young age is so common that it has become somewhat of a popular culture cliché, with the term frequently used for anyone living an extreme lifestyle. Whilst the excess-fuelled deaths of a number of young musicians is more than an unfortunate coincidence, it is a key part of the ideology and mythology of rock. As the musicologist Sheila Whiteley writes: "Self-destruction - whether drug-related, suicide or the result of severe risk-taking - is ... curiously related both to the excesses of a rock 'n' roll lifestyle and to much of the litany of its songs" (Whiteley,2005, p 157). These excesses are embedded in rock’s culture, founded upon a belief in interrelated personal and aesthetic freedoms.

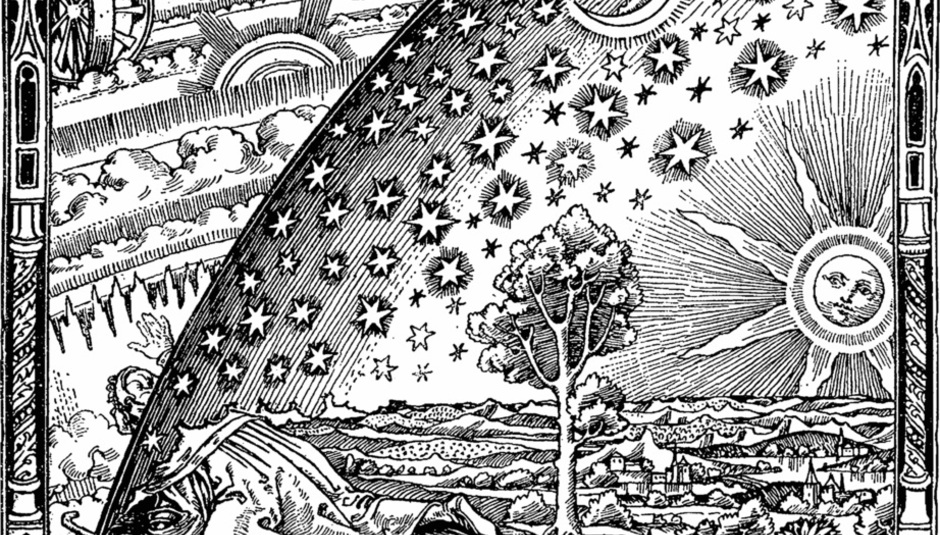

Artists are individuals with their own particular vision and their lives are seen as something exceptional as they set themselves in contrast to the "conformist masses". They are "rebels", standing "outside" society in order to critique it, often by indulging in acts that "common morality" considers taboo. As Matthew Bannister writes in his White Boys, White Noise: "The suggestion is that the artist or art articulates what normal society represses - if normal society appears healthy, the artist expresses its hidden sickness" (2006, p.137). The idea of the artist being "outside" society quite literally ties into the Latin derivation of the word "sacred" - something "set apart" from regular, secular society. This leads vitally to ideas of religion and mysticism found in rock culture (and the idea of celebrity in general) with its pantheon of gods. Music and drugs become a way of seeking a sense of transcendence, defined by Wiktionary to mean:

1) The act of surpassing usual limits. 2) The state of being beyond the range of normal perception. 3) The state of being free from the constraints of the material world, as in the case of a deity.

However, in being seen as “exceptional”, otherwise ordinary musicians risk their mental and physical health.

No God Only Religion: Romanticism

These ideas of artistic individualism and freedom would not exist in their current form if not for the artistic movement of Romanticism that started in the late 18th century and which became culturally dominant during the period 1800-1850. Romanticism was a response to the Industrial Revolution as well as the Enlightenment, both of which saw a great advance in the development of the sciences with a focus on ideas of progress, reason and rationality. Many artists and thinkers began to express growing doubts about this "progress", worrying that a "culture of feeling" (Blanning, 2011,p.8) was disappearing.

Enlightenment art tended to focus on the imitation of the "ideal beauty" found in the forms of ancient Rome and Greece and, as such, downplayed the role of the individual artist and their emotional state. In contrast, the Romantics (who included poets, composers and painters such as Wordsworth, Beethoven and Turner) "placed the creator, not the created, at the centre of aesthetic activity" (Blanning,2011,p.17). They retreated into themselves, creating emotional and personal works that featured themes excluded by the Enlightenment focus on the "rational" mind: madness, dreams, wild emotional states, mysticism, eroticism and opiates.

In contrast to the Enlightenment thinkers who had looked to stop believing in supernatural ideas such as religion, many Romantics instead shifted their focus from the traditional Christian view of a transcendent God above, to an immanent God that existed within nature and the body. Religious feeling wasn't abandoned but re-routed "either outward towards the depths of nature or inward towards the depths of the soul", while they sought "to preserve the religious experiences of the believer, the feeling of mystery, of ecstasy, of yielding to the infinite" (Ferber, 2010,p.66). God’s profound powers were now found "in nature... and in our own mind that responds to it" (Ferber, 2010,p.73).

These passionate religious states could be found in the arts and "it was at this time that 'art' acquired its modern meaning" (Blanning,2011,p.36). The artist as an individual became more important and accordingly the idea of the god-like genius creator entered the popular consciousness. The idea of genius:

was greatly assisted by the secularisation of European society and the simultaneous sacralisation of its culture... For a growing number of educated Europeans, both traditional doctrines and traditional institutions were no longer sufficient. They looked to art in all its various forms to fill the transcendental gap that was opening up (Blanning,2011,p.36).

Artists became the Gods, Art the new religion.

If the mind and imagination were sacred, then the mind of a genius and the work it creates, were doubly so.

Artists were encouraged to follow their own ideas, irrespective of what the mass audience demanded. Romantics referred to the "uneducated" public as "philistines", adapting a biblical metaphor first used by German students who, in a feud with townspeople, began to use it to ridicule the uneducated. The stereotypical philistine was only interested in the material world of work and family and saw nothing outside this world as important. By seeing themselves as "exceptional" outsiders, the artists no longer had to play along with normal ideas of taste or even morality.

The concept of genius was partially a shield from the demands of the audience. By musicians seeing themselves as "artists" and not "entertainers", their entire outlook on their work could change; the audiences' reaction was less important. For example, orchestral music at the turn of the nineteenth century changed from music that amateurs could easily reproduce at home, to the more complex art aimed at connoisseurs that we now recognise as "classical music". In her account of classical, serious, music culture, Tia Denora describes how Mozart's later more complex work alienated his listeners: "In secular arenas and in 1780s Vienna, music was meant to entertain, it was not yet commonly conceived of as an end in itself" (1997,p.16). Music was often composed for an important event but it would not generally be re-used, it was simply old music. After Mozart's death in 1791, the early strains of Romanticism saw his posthumous reputation growing as he became one of the "great composers" and was deified as "the immortal Mozart". The canonisation of his work as that of a "great artist" thus meant his work was "to acquire magical and occult properties that are in fact very ancient" (Kermode, quoted in Jones, 2008, p.9).

The passionate religious states that the Romantics sought could also be found in opium; amongst the many who experimented with it were the poets Byron, Coleridge, Keats and Shelley and the writer Thomas De Quincey. In his Confessions Of An English Opium Eater (1821), De Quincey described his use of opium in a way that would make a significant mark on the Romantic imagination. His description of his first use was intentionally mystical, contrasting the "wet and cheerless" London Sunday afternoon with "the celestial drug" of opium. Even the salesperson who sells him opium is discussed as a quasi-religious figure: "he has ever since existed in my mind as the beatific vision of an immortal druggist, sent down to earth on a special mission to myself" (p.22). In his introduction to Confessions, Barry Milligan writes that De Quincey's example "almost singlehandedly changed opium's popular status from the respectability of a useful medicine to the exoticism of a mind-altering drug" (2003,p.xiii). This led the drug to become "a mainstay of the bohemian image" (2003,p.xxxiii) and inspired the idea "that artistic capacity is expanded by psychoactive drugs"(2003,p.xxxv).

Desolation Angels: The Beats and Rock Culture

These themes in Romanticism have been vastly influential to modern society. One of the important ways they entered the rock lexicon was through Jack Kerouac, William S. Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg, the core of the group of writers known as the "Beat Generation". The Beats were explicitly influenced by the Romantics - notably William Blake, later American "Transcendentalist" Romantics such as Henry David Thoreau and Walt Whitman and the Romantically-influenced French symbolist poets Arthur Rimbaud and Charles Baudelaire. Kerouac describes the beats as: the subterraneans (sic) heroes who'd finally turned from the "freedom" machine of the West and were taking drugs, digging bop, having flashes of insight, experiencing the "derangement of the senses," talking strange, being poor and glad, prophesying a new style for American culture (2007,p.559)

The Beats followed in the Romantic path of seeing drugs and alcohol as a path to wisdom. The group experimented with a variety of different drugs while, unfortunately, Burroughs became a long-term heroin addict (detailed in the DeQuincey-esque memoir Junkie (1953)) and Kerouac became an abusive alcoholic (eventually leading to his death at 47). Ginsberg, Burroughs and Kerouac (among a much larger group) explicitly connected their freedom of lifestyle with their writing and even their writing styles.

Keroauc's most celebrated novel, On The Road (1957), dealt with the freedom of the open road as well as taboo topics such as alcohol, sex and drugs, becoming "arguably the seminal text for rock rebellion" (Reynolds and Press, 1995,p. 8). Kerouac encouraged the idea of "spontaneous writing", doing so without editing or revising, thereby aiming to write like a jazz musician improvises. In the introduction to one of his books, Kerouac described his writing as: "the prose of the future, from both the conscious top and the unconscious bottom of the mind... Not a word of this book was changed after I had finished writing it in three sessions from dusk to dawn" (2007,p.481). As W. J. Rorabaugh writes in his American Hippies (2015): "Spontaneous music and writing formed a larger pattern of spontaneous living. If society was rotten and corrupt, then its rules were putrefying and immoral. Only by freeing oneself from all rules could one free oneself from the evils of society" (p.24). In the same way as the Romantics, the Beats were trying to free themselves from reason which they believed was at fault for society's problems. Crucial to Kerouac's writing is the vision of the road as representing new experience, the possibility of escape and a refusal to be tied down. By literally running away from home, one attempts to escape reality as it really is. Kerouac was keen "to teach a 'religious reverence' for 'real life'... to reveal the 'sacred' in the 'profane'" (Coupe,2007, p.2).

This idea was heavily influenced by the Romantics as well as his interests in Buddhism, Catholicism and mysticism. For Kerouac, this tied into his search for new opportunity, freeing himself from traditional moral restraints and a "rational" writing style. As Laurence Coupe writes: "The Beat ideal, then, is the beatific vision. That ideal stands opposed to the materialism of contemporary civilisation: 'materialism', that is, in both senses of the word - the denial of spirit and the pursuit of possessions" (Coupe, 2007, p.3).

Burroughs' best-known novel is Naked Lunch (1959), a non-linear journey through a surreal group of settings and characters, some of which are autobiographically inspired. Prominent in the book are themes of heroin addiction and graphic gay sexual encounters. The writing style of the work often used what Burroughs called "cut-up" and "fold-in" techniques, in which text is sliced up and re-arranged to create unusual juxtapositions that the conscious mind would not be able to create. Burroughs believed that his collage writing technique could both see into the future and break through the system of authoritarian control of language and the rational mind. The book, unsurprisingly, faced obscenity trials and was banned in several places. While Burroughs did not subscribe to Kerouac's more orthodox religious quest, his works are heavily influenced by ideas of mysticism, magic and an urge to experience "a reality beyond that accessible to our five senses" (Conway, 2014, p.13). As Burroughs once said: "My viewpoint is the exact contrary of the scientific viewpoint. I believe that if you run into somebody in the street it's for a reason" (Burroughs, quoted in Stevens, 2014,p.18)

We can see that the Beats, like the Romantics, saw themselves in contrast to the conformist masses. Their work often focuses on personal experience in semi-autobiographical work, often exploring the subconscious and what had previously been considered the private. Kerouac's need for new adventures and Burroughs' distaste for authority, as well as his heroin use, set them apart from the "square" world of post-war America with its conservative politics, sexuality and morality. As Howard Cunnell writes: The political and cultural climate of 1948 meant that discussions about the responsibilities of artists and intellectuals commanded a sharp urgency. A post-war, post-Atomic bomb, cold war culture of surveillance and fearful conformity, mashed anxiety and paranoia and was joined to the hamster-wheel existence of what Japhy Ryder in The Dharma Bums calls the imprisoning system of "work, produce, consume, work, produce, consume" (2010, p.4)

The Beats went on to be a direct influence on the sixties counter-culture, the hippie movement and the "serious" rock movement that grew out of fifties rock 'n' roll. Bob Dylan would say the Beats had as big an impact on him as Elvis, while The Beatles included Burroughs on the cover of Sgt. Pepper and both became good friends with Ginsberg. Original Beats like Ginsberg and Neal Cassady, the subject of Kerouac's On The Road, were key players in the hippie scene and while Kerouac and Burroughs were sceptical of the movement, their ideas were hugely influential. Steve Turner writes that "everything that the archetypal rock 'n' roll star of the 1960s and 1970s experienced - marijuana, amphetamines, hallucinogenics, homosexual experimentation, orgies, alcoholism, drug busts, charges of obscenity, meditation and religious engagement - had already been experienced by the Beats during the previous two decades" (Turner, quoted in Warner, 2013,p.22).

The Romantic idea of the rebel artist continued into the Beats and was then picked up by the burgeoning rock musicians. The Beats’ freedom of lifestyle and the subsequent influence it had on their work became a key part of rock culture. The rock 'n' roll entertainers of the 1950s were followed by the rock artists of the 1960s, with their attitude towards the audience changing accordingly. The difference in attitude can be seen if the two are compared, as Simon Frith writes in reference to the early British rock 'n' rollers:

Tommy Steele, Cliff Richard and Britain's other original rock stars experienced no tension between their music and their success; art and commerce were integrated. Popularity was the measure of their talent as entertainers, and if there were elements of rebellion in rock 'n' roll they were directed not against the structure in which the musicians worked, but against the adult generation to whom it was not, anyway, intended to appeal (1978,p.164)

In the 1960s, this attitude changed and rock became about satisfying the artistic vision of the creator rather than satisfying an audience (although paradoxically this new "mature" rock music became wildly successful). The musicians' lifestyles also began to change as they saw rock music as an escape from middle-class values as well as commercial interests. Simon Frith and Alan Horne note that through this process "pill-popping hedonism could ... be redefined in terms of bohemian 'liberation'" (89). The sociologist Howard Becker observes this tension in a group of jazz musicians he studied:

From the idea that no one can tell a musician how to play it follows logically that no one can tell a musician how to do anything. Accordingly, behaviour which flouts conventional social norms is greatly admired. (137)

As Becker explains, "Musicians feel isolated from society and increase this isolation through a process of self-segregation" (p.136). In becoming "outsiders", this isolation is romanticised and they become seen in quasi-religious terms by many of their fans.

In the late 1960s, this process of excess began to take its toll, leading to the mythical "27 club" where between 1969 and 1971 Brian Jones (of The Rolling Stones), Jim Morrison (of The Doors), Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin all died from excess-related deaths at the age of 27.

Break On Through (To The Other Side): Jim Morrison and The 27 Club

The Doors were a key part of the intellectualisation of rock music that occurred in the 1960s. The band had keen interests and backgrounds in the "serious" musics of jazz, folk, blues and classical, while both Morrison and keyboard player Ray Manzarek attended the arty UCLA film school. The band, and especially Morrison, were exceptionally well-read, having been particularly inspired by the Beats and Romantic poetry. As Reynolds and Press write: "from these Romantic influences Morrison derived the idea of the artist as a 'broker in madness', an explorer of the frontier territories of the human condition" (p.188). On the subject of Kerouac, Manzarek once stated: "If he hadn't written On The Road, The Doors would never have existed ... that sense of freedom, spirituality and intellectuality ... that's what I wanted in my work" (p.2, The Doors Companion, Rocco).

The Doors’ psychedelic rock music (generally on their early work as opposed to the blues-rock later sound) is suitably Romantic as it looks to explore the psyche (which translates from Greek as 'mind') and aims to give the listener a "temporary trip into psychosis" (Reynolds, Press, p.143). Through their use of jazz improvisation on "Light My Fire", Indian raga influence on "The End" or the ever-present eerie organ, the band's music evokes an, admittedly very 1960s, idea of the otherworldly and the subconscious. Their aim to provide the listener with a transcendent experience is suggested in their name, which comes from the Romantic poet William Blake:

“If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is, Infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro' narrow chinks of his cavern.”

The band took their name from this quote via Aldous Huxley's The Doors Of Perception (1954), which details an experiment with the use of the psychedelic drug mescaline. The band aimed to provide a psychedelic experience intended to allow the listener to cleanse their "doors of perception" and experience infinity. For the Romantic, the cleansing of these doors will allow us to experience everything that the rational mind shuts out. Morrison stated that his intention was to be something akin to the Native American shaman:

"The Shaman ... he was a man who would intoxicate himself. See, he was probably already an ... uh ... unusual individual. And, he would put himself into a trance by dancing, whirling around, drinking, taking drugs ... Then, he would go on a mental travel and ... uh ... describe his journey to the rest of the tribe"

In practice however, Morrison "was apparently a nigh compleat (sic) asshole from the instant he popped out of the womb until he died in that bathtub in Paris" (Bangs, p.130). Morrison was an abusive alcoholic who romanticised his own self-destruction under the rubric of self-discovery, an accusation that might also be levelled at Kerouac and Burroughs before him. Morrison's charisma and penchant for mysticism and self-deification saw him become a god-like figure, especially after his death. In his biography of Morrison No-One Gets Out Of Here Alive (1980), the former manager of the Doors, Daniel Sugerman, says he believed Morrison to be "a modern-day God" while Morrison's grave exists as somewhat of a shrine to the singer to this day. As Lester Bangs writes:

In a way Jim Morrison's life and death could be written off as simply one of the more pathetic episodes in the history of the star system, or that offensive myth we all persist in believing which holds that artists are somehow a race apart and thus entitled to piss on my wife, throw you out the window, smash up the joint and generally do whatever they want (p.132)

The lives (and deaths) of stars such as Morrison have set the blueprint for rock and roll behaviour and ideology for musicians since then. In the '70s and '80s, several significant hard rock musicians died following heavy drug and alcohol binges including Keith Moon (The Who), Bon Scott (AC/DC) and John Bonham (Led Zeppelin).

Kurt Cobain is a particularly important example. As an outcast growing up in a troubled family he found solace in punk rock eventually developing a serious heroin habit. Significantly, Cobain used many religious symbols in his band Nirvana - a Buddhist term for a transcendent state free from suffering and desire. Cobain was also a William Burroughs fan even going as far as collaborating with him on the release The "Priest" They Called Him (1993). Cobain died in 1994 at the age of 27 from a self-inflected gunshot wound after having long suffered from addiction and depression. More recently the soul singer Amy Winehouse died at the age of 27 after a highly public battle with addiction and alcoholism. Her death led to a discussion on the role of the press and music industry in leading to the destruction of stars. The singer was often somewhat of a figure of fun as well as a paparazzi favourite while her serious issues, including those of mental health and an eating disorder, weren't taken seriously. Winehouse's struggles gave the tabloid press a chance to exploit her struggles for their own profit as it fits into our own morbid interest in the rockstar narrative. These ideas of rockstar decadence also exist in other genres (themselves heavily influenced by rock music) such as in the hard-partying worlds of dance music and hip-hop while narratives of addiction are a key part of music biopics like the Johnny Cash film Walk The Line (2005) or the Ray Charles film Ray (2004). In many ways, the recent deaths of David Bowie and Prince are a reminder that the majority of musicians will meet less romantic ends as they inevitably fade away rather than burn out. Although during his "Thin White Duke" phase (1974-1976) Bowie was at the edges of a powerful cocaine addiction while, at the time of writing, rumours are swarming about Prince's possible prescription opioid addiction (although the source for this is The Daily Mail).

Popular musicians, in seeing themselves as artists, changed their relation to their audience and began to think of themselves as rebel outsiders rallying against the world of "the squares". This thought process arose as musicians increasingly adopted the mindset of the Romantics, often through the Beats. The artist then seeks to live in contrast to the world of the "philistine" a world of authority, damaging "rationality" and economic and spiritual materialism. Drugs and alcohol become increasingly important as they are both outside the square world of sobriety and they break down the walls of rationality imposed on the mind. The "doors of perception" are opened and the mind is able to be free to experience infinity. In taking these trips into the mind, the artist then seeks to represent it in their music through a sense of rebellion and the unknown. These ideas of transcendence and genius still show their deep origins in religious thought. Anything outside the material, rational world seems exciting in this mindset which can lead to a romanticisation of disorder and a celebration of mental illness as a sign of genius.

As Matthew Bannister writes, "misery is not just a psychic state, but also a form of cultural capital" (2006, p.134), he explains this further writing that "being "fucked up" becomes a kind of prerequisite for authenticity" (2006, p.137). For musicians to oppose conventional society, their mental and physical states are expected to oppose conventional good health and illness becomes fetishised.

Through all this we can see that, despite the increasingly secularisation of our society, religious feeling was never quite lost. We still seek something beyond the earthly, a " "manifestation of the sacred" as a release from the sense of being trapped in a merely profane realm" (Eliade, cited in Coupe, 2007,p.3). In this way, we look for everything outside of conventional existence to satisfy our belief that there's something more in this world. As the Romantic thinker A.W. Schlegel said, beauty itself is a "symbolic representation of the infinite" (Schlegel, quoted in, Vaughan, 1994, p11). So in music and drugs we manage to find something outside a mere world of appearances. We can then see that in these ways, we think about music on terms inherited from religion that can be damaging to the creative, but otherwise normal, human beings they are placed on. Our obsession with the idea of "live fast, die young" and the utopian idea of transcendence is ultimately an impossible and harmful narrative.