It was tough being in a rock band in India during the 60s and 70s. You could hardly get your hands on any equipment for a start, owing to the inflexible import laws. What you could get, you had to lug from city to city on rickshaws. Political uprisings and national warfare crushed nightlife in Bombay, pushing gigs out of their typical evening slots into morning jam sessions. And all of this was assuming you’d even managed to hear Western rock music, either by getting hold of bootlegs, or tuning into Radio Ceylon.

Despite all this, the Indian beat music scene was incredibly vibrant for fifteen years or so. With the exuberance of independence waning, but the hangover of British imperialism still in place, the youth of Bombay and Calcutta wanted to break free of their parents’ jazz, chicken kievs and prawn cocktails. Then the Beatles released Love Me Do. In an ironic twist of history, a new form of British cultural imperialism helped young people rally against the Empire, melding Western trends with Indian traditions. Fifty years later, an original LP by The Savages fetched £3,000 on eBay.

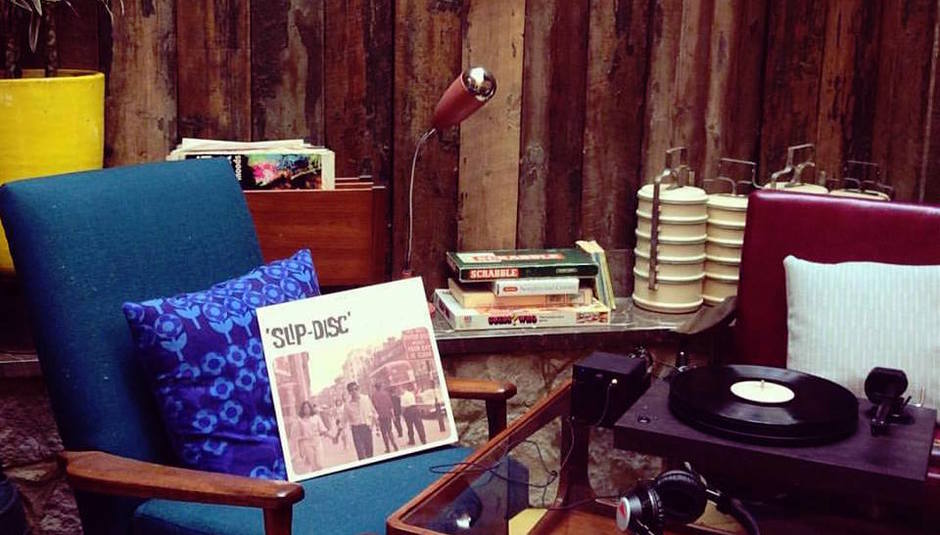

This was the scene which fascinated Shamil Thakrar when opening his newest branch of Dishoom, leading him to create a full compilation in homage to the era - Slip-Disc.

I meet him in his new restaurant, just opened on Carnaby Street. He’s a warm, energetic and enthusiastic, with a contagious love for detail and anecdote. He encourages me to try a Commander (with a slight warning that it might kill me) – a dry martini with an absinthe rim. The drink is named after Commander Nanavati, who turned himself in after shooting his wife’s lover in a calculated act of revenge in 1959. After a jury declared him guilty, the decision was overturned due to overwhelming public demand. It was the OJ or Oscar Pistorius celeb-trial of its time, Shamil tells me, clearly enjoying its gossipy undertones.

With this love of intrigue shaping even his drinks menu, there’s little wonder that Shamil was drawn to the cultural quirk of Western rock spreading across Indian cities. He pulls out a well-thumbed, highly notated copy of India Psychedelic by Sidharth Bhatia, a book which guided his research a great deal, and begins to tell me how he and Rob Wood – a long-time curator of his restaurants’ music – began to put the record together.

“It’s a nice cul-de-sac of history”, Shamil tells me. “It doesn’t really go anywhere, it’s just a neat little thing. I love music, and I’ve been into sixties rock since I was fourteen, and I’ve always loved my Beatles and Stones. Of course, the problem with the sixties is that it’s so riddled with clichés. But when we really looked into it, not only did we find there was great design in Bombay around which you could build a restaurant, but we also found out about the rock scene”.

The result is a stunning ten track compilation. It’s doesn’t just document the music of the time, but also showcases the influences in the margins, and reflects the first wave of Indian immigration arriving in London at the time as well. Songs like ‘Born To Be Wild’ by the Savages are quintessential examples of the actual beat music of the time; teenagers playing covers in restaurants to people unexposed to the originals. But artists like Gabor Szabo hint at the jazz traditions which gave rise to the new scene. And the inclusion of Blossom Dearie is – Shamil admits – “just an indulgence. It just feels like London in the sixties”. It’s deliciously broad.

“We had two directions we could go in”, Shamil agrees. “One was a history lesson. We definitely could have gone: this was all the Bombay rock at the time, and that's that. But we went for something a bit more impressionistic and a bit more interesting, and I definitely think we came out with a better record, even though we sacrificed some of that purity.”

The choice to follow all of their passions and instincts has resulted in a brilliantly alive compilation, which echoes the expansive ethos of Dishoom as a whole. Ostensibly, they’re based on the Iranian cafes of Bombay, but they incorporate so much more than that.

As political refugees fleeing religious persecution in late 19th and early 20th centuries, Iranians were outsiders in society. This helped them to create spaces for common people to eat out for the first time, in cheap and inclusive spaces. 500 existed at their height. Now only 20 remain. And while Shamil puts their influence at the heart of his restaurants, his larger vision goes much wider.

He gives me a tour of the new place, explaining his far reaching influences for everything from jokey posters to the minutest details of wall panelling. It goes way beyond accurate representation of Iranian cafes, while always sticking to their spirit. The compilation is similar. It’s removed from specific time and place, while beautifully evoking the idea of an era. These ideas are related. “There’s no difference between design and music”, he tells me as we walk around the restaurant, looking at pictures of the compilation’s artists on the walls.

Pushed for a favourite artist on the record, Shamil goes for Asha Puthli. “She’s so cool”, he tells me giddily, “we’re friends on Facebook now!”

Her version of Marvin Gaye’s ‘Ain’t That Peculiar’ is a brash, soulful, colourful turn, and makes her 1973 solo debut an immediate must-hear. And of course, Shamil can’t resist sharing the tale of how Asha ended up knocking about with Andy Warhol, who stole her idea (she claims) of putting a zipper on the front of an LP. That ended up being the Rolling Stones’ ‘Sticky Fingers’ artwork, with no credit to Asha. But as fun and engaging as his stories are, the music itself is always just as interesting. These ten songs are all gems.

Slip-Disc spans decades and genres to give a stark impression of both London and Bombay in the 1960s – with all its associated characters, foods and sounds. The opening track encapsulates the whole thing perfectly: a version of Jumpin Jack Flash by Ananda Shaknar, slathered with sitar. And as strong as it is on its own terms, it’s is just as valuable for being a portal into a world of music and culture we have little idea of here in the UK, urging you to explore further.

Its plurality and inclusiveness make perfect reflections of the ethos of the restaurants which inspired it – and it's as at home in London today as it would have been in Bombay or Calcutta in 1965.

You'll find more info about the compilation over at dishoom.com.