Ed Ledsham explores the history of auto-tune... (Listen to Auto-tune Anthems on Spotify).

"Auto-Tune is great for fixing vocals, but we use Auto-Tune in a way it wasn't designed to work. A lot of people complain about musicians using Auto-Tune. It reminds me of the late '70s when musicians in France tried to ban the synthesizer. They said it was taking jobs away from musicians. What they didn't see was that you could use those tools in a new way instead of just for replacing the instruments that came before. People are often afraid of things that sound new." Thomas Bangalter (Daft Punk)

Technology has long held an uncomfortable position in music. Part of this discomfort inevitably comes from trying to understand technology's relationship to humanity and leads to an artificial separation of the two into dubiously separate spheres. From modern-day DJs exclusively using vinyl, to "March King" John Philip Sousa attacking recording technology, there has often been a mistrust of the supposedly new and technological in music. Auto-tune is just one of many examples of a technology being attacked for its supposed lack of authenticity, humanity or emotional content. Many fail to see either the increasingly creative uses of the technology or their own hypocrisy and elitism in attacking something as "technological".

When producer and musician Steve Albini was asked by The AV Club to nominate a song he hated, he chose Cher's "Believe", the song best known for introducing the world to auto-tune.

Albini outlines how he believes the effect (or any "production gimmick") is faddish, comparing it to a trend at his high school that saw girls wearing their hair like Farrah Fawcett:

"Whoever has that done to their record, you just know that they are marking that record for obsolescence. They’re gluing the record’s feet to the floor of a certain era and making it so it will eventually be considered stupid." avclub.com/article/steve-albini-integrates-the-history-of-music-fads--88812

The implication is that the music Albini is making (rock) is timeless and does not adhere to fads, while the devices that he uses to make that music (electric guitars, mixing desk, distortion effects) are not "technology". In this way, we see a commonly held misconception about what technology actually is (heavily encouraged by marketing departments looking to persuade us that we need a new iPhone/dishwasher/car).

As the musicologist Timothy Taylor notes "after a period of use, most technological artifacts are normalized into everyday life and not seen as "technological" at all" (Taylor, 2001, p.6). We then see items at the vanguard of science to be technological, whilst discounting others that are equally so - such as the electric guitar, the piano or the snare drum. By no longer regarding these as technological, and incorporating them into a seamless history of musical instruments, we ignore the inevitable disruption that occurred at their initial introduction. This disruption occurs when, at the advent of a new musical technology, attacks are made as musicians attempt to work out age-old questions of separating human "art" from mechanical "craft". To use the example of the introduction of the player piano:

"Musicians, music teachers, and composers opposed the new machine, contending that one could copy sound but not interpretation; that mechanical instruments reduced the expression of music to a mathematical system; that amateur players would disappear, and that mechanized music diminished the ideal of beauty by "producing the same after same, with no variation, no soul, no joy, no passion"" (Pinch, Bijsterveld, 2003, p.540)

The shock and controversy caused by a new instrument is an example of what the sociologists Trevor Pinch and Karin Bijsterveld (using the terminology of Harold Garfinkel) identify as a "breaching experiment". This is where a social rule (such as queuing) is broken (queue-jumping), provoking a reaction from the subject. After the rule is broken it is possible to study the breach, identify the unspoken assumptions and then consider them. According to Pinch/Bijsterveld, in music "such interjections provide an opportunity to rehearse arguments about what counts as part of music and art and, conversely, what is appropriately delegated to machines".

Heartless: All My Favourite Singers Couldn't Sing

The use of auto-tune in recent popular music has led to such a breaching experiment. In 2009, the indie rock group Death Cab For Cutie attended the Grammy's wearing blue ribbons intended to "raise awareness about Auto-Tuner abuse". Death Cab singer Ben Gibbard complained that the software led to fewer "actual people singing and sounding like human beings", claiming that real singing "gives the recording some soul and some kind of real character", while bassist Nick Harmer said "musicians of tomorrow will never practice. They will never try to be good, because yeah, you can do it just on the computer." This assault on auto-tune sounds similar to those on the player piano; there is a similar concern for "amateur players" while the phrase "soul" is explicitly echoed in each with Death Cab longing for the sound of "actual people" "sounding like human beings" with "real character" (emphasis added). Musicians of the old guard tend to see the new technology as allowing inept musicians to enter their craft and failing to understand their talents: "you can do it just on the computer".

We can now see which ideas about music have been breached: technology supposedly makes music "soulless", robbing it of its humanity, whilst its ease of use allows "any idiot" to make music. These ideas can be traced back to the ideology of mass cultural criticism within rock culture that prizes individualism and humanity as opposed to "worthless pop music". As musicologist Keir Keightley notes:

"Dismissing music as 'machine-made' ... signals a suspicion that the musical experience in question has been alienated, through the intervention of forces that are somehow anti-individualistic, and thereby inauthentic." (p.133)

This argument holds that machines are a tool of big business capitalism that are corrupting otherwise "pure" human forms of folk music or high art. Technology is seen as an enemy to be mastered by humans, its eventual assimilation as an "instrument" only occurring after an initial period of interruption. This process also has the effect of making older technology seem more authentic (see vinyl, acoustic guitars, anything said by techno producers). Looking deeper into these beliefs about technology starts to reveal their paradoxical nature.

Keir Keightley's ideas about romantic authenticity in rock music are relevant here. Romanticism was a "response to the social dislocations of the Industrial Revolution" and "value[s] traditional, rural communities, where life could be lived close to nature". In musical terms this means "liveness", "’natural’ musical sounds", "tradition and continuity with the past" and most importantly "hiding musical technology". Romantic authenticity is often sought by musicians attempting to return to their "roots", especially after an excessive modernist period in music.

One of the main illusions held by romantic rock culture is the belief that a recording is a realistic, unmediated presentation of the artist(s) playing "live" to you (the audience). As Mark Katz puts it:

"We cannot dismiss the documentary value of recordings, for they tell us a great deal about the musical practices of the past. But the discourse of realism ignores a crucial point: recorded sound is mediated sound". (Katz, 2004, p.2)

While musical recordings might have started with the intention of capturing a live recording, in practice this is an impossibility. The microphone - or recording horn at first - is not the human ear; recordings preserve certain frequencies, with each individual microphone (and there are many) colouring the sound in its own way.

Katz writes about "phonograph effects" which are, essentially, the musical changes that recording technology has allowed to develop. Katz notes that the history of recorded music has involved many changes to the "original" live music, as for instance on early acoustic recordings where brass instruments often replaced strings as they came through clearer. Recording has since become a much more complex process with the advent of microphones, magnetic tape, multitrack recording, studio effects, equalisation and powerful computer software.

Across the continuum of current popular music, there is music that deals with its technological mediation in a variety of ways - with everything from that trying to hide it to that gleefully embracing it. These recordings are often made in essentially the same way, but while some are treated as authentic performances by talented musicians, others are treated as soulless studio constructions composed by computer. Auto-tune software is often used on both sides of this spectrum in two very different ways. There is the invisible use of auto-tune as a studio editing tool where it corrects mistakes, defended here by studio engineer and musicologist Steve Savage:

"Before Auto-Tune I had numerous debates with singers about a particular phrase that I felt was especially emotional and effective but had one slightly sharp or flat element. I’d say “But the performance is great! No one is going to notice that tiny pitch issue.” Often the singer “just can’t live with that line” so we’d record it again. (We’ve been fixing pitch in vocal performances by re-recording for a long time.) However, when we’d re-record the line, invariably it wouldn’t be quite as emotional or expressive, but it would be more in tune. The singer would be satisfied and I’d be disappointed. Now, thanks to Auto-Tune, I can pitch fix the little problem and save that great performance." blog.oup.com/2012/06/why-auto-tune-is-not-ruining-music

Savage's testimony challenges the widely-held belief that auto-tune is allowing talentless hacks to sing and more a continuation of post-production and editing techniques that producers have used for years.

808's and Heartbreak: You Know We Some Weirdos

"The adaptation to machine music necessarily implies a renunciation of one's own human feelings" - Theodor Adorno

Auto-tune was originally intended to be used for invisible editing. However, as is often the way with musical technology (see feedback, distortion), an unintended side-effect was found to be aesthetically pleasing - with the effect turned up to a high setting, tonal change is flattened and digitally altered to stick to the desired pitch. This aspect of auto-tune is somewhat similar to the talkbox and the vocoder (for which it is easily confused).

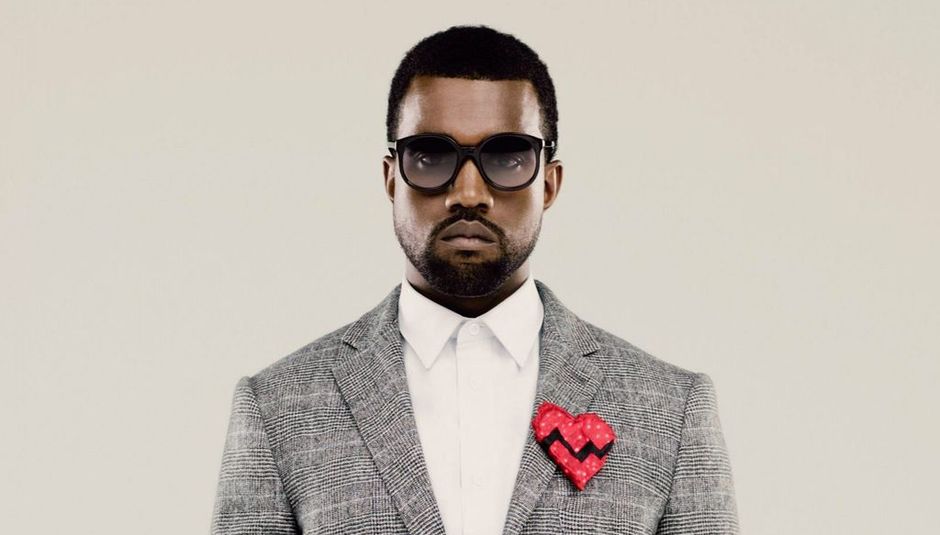

It could be said that there are three fairly different stages in the popular consciousness of auto-tune. At first it was the "Cher effect" from its use on "Believe" (1998) to tracks like Daft Punk's "One More Time" and in euro-dance. After that went out of style, it become the "T-Pain effect" as the rapper/producer used it on a chart-topping series of singles starting with 2005's "I'm Sprung". T-Pain's use of the effect again became incredibly popular in chart-topping R&B and rap songs before again starting to go out of vogue. The effect then entered the 808's and Heartbreak stage, where rappers like Lil' Wayne and Kanye West began to explore it as a more experimental and emotional tool, leading to a renewed surge of popularity in Atlanta and Chicago hip-hop. Complex writer Kyle Kramer notes that this stage's "sound is less pop and more of a druggy emotional haze".

As if to actively challenge the idea that auto-tune or technology generally leads to emotionless, robotic music, Kanye's 808s and Heartbreak used the effect for a sparse breakup album where he frequently abandoned rapping for singing. This template has been hugely inspirational for a whole generation of rappers following West, who have increasingly blurred the line between rapping and singing while expressing a far wider range of emotions than was previously prevalent in hip-hop. Consequently "the decision of two of rap's biggest stars [Kanye, Lil' Wayne] to start sounding melodic and emotionally vulnerable worried hip-hop audiences"(Kramer, 2014, Complex).

Many of the attacks levelled at these auto-tuned rappers are attacks on their masculinity and sexuality, something that echoes the original reception of crooners such as Frank Sinatra and Bing Crosby who also relied heavily on a new technology for their vocal style. The "crooning" vocal style was made possible by advances in microphone technology that allowed singers to sing softly into the microphone and achieve a sense of intimacy with the audience. The crooners were immensely popular with teenage girls who became known as "bobby soxers" in a 1940s analogue to One Directioners/Beatlemania/Lisztomania. Simon Frith notes that, in 1936, Cecil Graves controller of programs at the BBC attempted to ban crooning from the radio. Frith explains that:

"The essence of the BBC case against crooning was that it was 'unnatural'. 'Legitimate' music hall or opera singers reached their concert hall audiences with their voices alone; the sound of the crooners, by contrast, was artificial... Crooning men were particularly unnatural - their sexuality was in question and they were accused of 'emasculating' music." (Frith, 1987, p. 264-265)

The parallels with the singers/rappers Future, Drake and Young Thug are immediate . Drake's perceived lack of masculinity is mocked constantly, inspiring the "Drake the type of" meme, while Young Thug has had his sexuality widely questioned. Even Kanye West was attacked as a "pioneer of this queer shit" by self-described "hip-hop conservative" Lord Jamar. These rappers are not known for embodying the hypermasculine hip-hop pose of yore; they don't show their masculine strength through their verbose and dextrous flows (rapping isn't compared to sword fighting for nothing), their voice is often a heavily-processed melodic half-sung rapping style rather than an authoritative and macho bark and they often transgress traditional masculinity with their embrace of fashion or their fondness for ballads. While these rap/singers often sound frail, hurt, melancholic and occasionally exuberant, that is not to say that their music navigates entirely away from alpha male masculinity; it still features large amounts of the gross misogyny that is unfortunately common in hip-hop. Still, listening to tracks like Future's "Turn On The Lights", Ty Dolla $ign's "Never Be The Same", Young Thug's "Shooting Star" or Kanye West's "Blood On The Leaves" you can hear a broadening of the often narrow emotional colours previously open to rappers.

Authorship: Future Hendrix

When listening to contemporary rappers like Drake or Young Thug, it is almost impossible to miss the role of the producer, whose name will often be made apparent with an audio signature a few seconds into the track (Mike-Will-Made-It, DJ Mustard). Hip-hop currently has a litany of highly prolific, Phil Spector-like hitmaker/producers with many rappers working very closely with their producer or producing themselves (Kanye, Travi$ Scott, Ty Dolla $ign).

As Mark Costello points out:

"Digital recording ... divides the responsibility for the final 'song' more or less equally among the performer, the engineer at the mixing board, the producer who coordinates the multitracking and mixing process, and the electronic hardware that actually 'makes' the music" (Costello, p.62)

This is anathema to the romantic rock tradition as musicians consider their sounds to be mere sounds rather than a part of the composition itself. In electronic music from hip-hop to EDM, the sound of a vocal or the kick drum are the composition. Steve Albini famously refers to himself as an engineer, refusing to take any songwriting credits for his production on albums, believing his influence on the record to be a simple matter of mechanics rather than a creative input. When auto-tune is applied by a producer to correct vocal mistakes, it is immediately taken to be representative of the intrusion of the "inauthentic" studio into the "pure" voice. As Simon Frith notes "there is the problem of aura in a complex process of artistic production: what or rather, who is the source of a pop record's 'authority'" (267).

Consider the meme that compares Beyoncé's "Who Run The World?" to Queen's "Bohemian Rhapsody", listing the song as featuring six writers and four producers compared to Queen's one writer and one producer (although Queen should also be listed as producers on the track). The lyrics of the two songs are then contrasted, implying that the more complex lyrics of the Queen song are the only important part of the song (ignoring rhythm, melody, harmony and ALL sonics). The meme implies that having fewer producers featured on Queen's song gives the song more credibility while simultaneously confirming Freddie Mercury as the song's author-genius. The implication is also that Beyoncé is a puppet of her producers and writers (although she is both producer and writer). This is a particularly gendered attack, as female artists are often seen to be the mere singers on their work, ignoring their authorship as songwriters and producers (Taylor Swift, Grimes) or simply ignoring their talent (Nicki Minaj).

In a romantic rockist attitude, the sound of the guitars or the vocal sound is the work of a mere technician, whilst in electronic music (hip-hop, R&B, EDM, etc.) it is a part of the song. However, in "modernist" rock music (psychedelic rock, post-punk, shoegaze, post-rock), the line between musician and producer is increasingly blurred, resulting in producer/musician auteurs like Brian Wilson, Jimi Hendrix and Kevin Shields. This seems to be an attitude of particular interest to many rapper/producers, with the rapper Future referring to himself as Future Hendrix. In this way, Future treats his voice the way Hendrix treated his guitar, as a source of sound to be experimented with.

Auto-tune strikes right at the heart of difficult ideas about humanity, creativity and authenticity in popular music. The human voice is clearly an important part of how we understand music as it evokes the presence of the author, communicates their message and establishes intimacy with the listener. The idea, however, that "technology" is "ruining" music is a glaring example of what's known as technological determinism; the belief that technology is an external, alien force rather than something designed and used by humans (and often not in the way it was originally intended). As Nick Prior writes:

"Music is always already suffused with technology, it is embedded within technological forms and forces; it is in and of technology. It is certainly not a peripheral tool that enables a pre-existing creative humanity to come spilling into sonic communities." (p.11)

All music makes use of technology - from rural folk music to grand classical music - but as each technology becomes naturalised, we no longer see it as an interjector into a supposedly pure, human musicality.

In some ways the whole issue comes down to an idea that the science fiction writer Philip K. Dick spent much of his career trying to answer: are the things a machine does any less valid, real or, dare we say it, human than that of a human?

You can follow Ed Ledsham on Twitter @Eledsh.

Listen to Auto-Tune Anthems on Spotify

Any requests for our Auto-Tune Anthems playlist? https://t.co/WTQkMIte58

— DrownedinSound (@DrownedinSound) September 27, 2015