The recording studios where your favourite albums are made are in the most ordinary places. You walk past them every day without realising it - in unassuming houses, on residential roads and the back of run down practice rooms, bands slog away and pay by the hour trying to turn nothing into something that gives you goosebumps.

Tucked down a side road yards from Elephant and Castle’s geographically intimidating subway, there’s a shabby grey door that opens on to a grubby set of stairs littered with bikes and amps. This is the entrance to The Maccabees’ cosy, messy studio where they’ve been making their new album for the past two years. “I’d offer you a cup of tea but I don’t think we have any milk,” Felix White says when I arrive. “I could pop out for some if you want?”

“We haven’t been here for a while so the mug situation is a bit...” singer Orlando Weeks adds. He’s just emerged from a cupboard-like piano room on the staircase. Guitarist Hugo Weeks is on a window sill, quietly worrying a guitar. It’s all a bit less rock’n’roll than it is The Office. The Maccabees are extremely pleasant, thoughtful young men with £5 names and 50p accents. It’s hard to imagine them chucking TVs into swimming pools or dropping molly “in the club” - although to be fair to them, it is currently 11am on a Monday morning. Swerving scandal, burn-out and bust-ups, they’ve been plugging away for a decade trying to become who they are - and with their new album, they think they might just have managed it.

A sort-of concept album, Marks To Prove It follows the basic arc of a night out in South London - from the promise of the evening as you head out, to the literal sounds of the nightbus as you journey home alongside the 4am people on their way to work. It’s an older, more contemplative record than 2012’s Given To The Wild but hangs on to a bit of the boyish charm of early Maccabees when they were writing songs about municipal leisure centres and thwarted trips to Disneyland.

“On the first album some people said, ‘Oh yeah, it sounds a bit like Futureheads’ - and yeah, it did sound a bit like Futureheads. I loved the Futureheads,” Felix says. “And on the second one it was like ‘Oh, it's got a bit more Arcade Fire-ism’ and we did love that record so it did sound a bit like that. But I don't think this record sounds much like anyone else other than, just, like, The Maccabees.”

But that doesn’t mean it came easy. The band spent “a long time” trying things out, experimenting with new sounds and techniques and ending up with “hours and hours of nice and good, interesting music” but no real direction. Instead of cobbling together an album from what they had, they narrowed down the infinite musical choices by imposing limits. Everything had to be playable live, everything had to fit with the vague theme. “When we started trying to put those limitations in, it focused us,” Orlando says. ”We had a common goal. Because it’s very difficult when there’s lots of you with different, er...” - he pauses, struggling for the diplomatic word - “...tastes and ways of working and ambitions, to try and find that middle ground.” You get the feeling there might have been a few tense discussions along the way.

Making an album is a weird mix of magic moments and crushing mundanity.

Orlando sounds tired, describing the recording process as “endless hours where you're just sat there thinking I haven't done anything except sit here and listen to kick drum patterns.” You and I sit at computers colour-coding spreadsheets and endlessly scrolling through Twitter, The Maccabees sit and listen to the same drum fill for six hours. Making an album is a weird mix of magic moments and crushing mundanity.

“I really like the moments that at the beginning of writing where you start making something from nothing and trusting your instinct. Getting that little buzz when you think ah, that's something. That's a pleasure. I miss that. And then the rest of it, the recording, is trying to sustain and preserve as much of that original excitement as possible,” he says. To escape the monotony, Orlando taped a microphone into a bag and went out to record the sounds of the surrounding streets. “You suddenly feel like ahh, there is creativity and real life.”

“When we started trying to put those limitations in, it focused us,” Orlando says. ”We had a common goal. Because it’s very difficult when there’s lots of you with different, er...” he pauses, struggling for the diplomatic word. “...tastes and ways of working and ambitions, to try and find that middle ground.” You get the feeling there might have been a few tense discussions along the way. “It’s hard because we’re just out of doing it so you tend to just splurge out how difficult it was,” Felix adds, probably because it’s starting to sound like it’s been an absolute nightmare. “But probably every record has been hard, yeah.”

Even though they struggled to get to the point where the album was, finally, an album, it’s not supposed to sound like there are years of graft behind it. ”Every song has a backstory that can go on for a year or two,” Hugo, who produced a lot of the new record, says, “and the aim of creating that song and finishing that song is to forget and hide all the workings that get to it.”

“Yeah, you don’t want to be like ‘Oh, I’m listening to a slog,’” Orlando interjects. “‘This is a good slog. A good singalong slog.’”

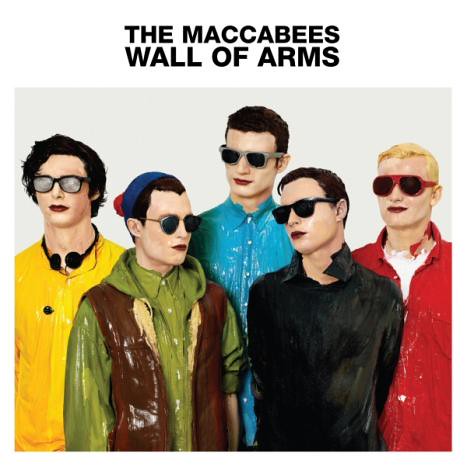

There’s no tension today, except when I try to explain the concept of Maccabees fan fiction (which exists) and awkwardly accuse them all of being 30 years old (which they are, thereabouts). They get excited about their childhood autograph collections, mess about with a tennis ball, laugh about a 0/10 review they once got and rib each other about the Wall Of Arms cover. The one thing Felix would have done differently across the whole of his Maccabees career is that Boo Ritson cover. “I would have not worn the yellow shirt and glasses and headphones on the Wall of Arms cover,” he says. “I would have definitely not done that. Everytime I look at myself I think” - there are no words for what he thinks, just a gagging sound - “Like I'm gonna be a little bit sick. I think I just look incredibly weird every time I see it.”

They struggle to come up with much they’d change about their career other than that, as if they’re afraid that even saying they’d do something differently would somehow change the past and lose them their success. As one of the few survivors of the great 2007 indie-boy buzz-band boom, The Maccabees are no strangers to how quickly a hyped up band can become a has-been. They sigh when I ask them why they think they’ve managed to sustain a career where others didn’t. “We do get asked that quite a lot,” Felix says before Orlando launches into a list of reasons that sounds quite rehearsed. A decent label, a mutually respectful working process, loyalty to each other, yadayadayada. A lot of luck, basically. Luck, freedom and a few really great songs.

“It did feel every other band that came out kind of shot to stardom above us, you know?” Hugo says. “But that whole thing to where we are now has worked in our favour. It's given us time to develop.” That slower climb is part of the reason The Maccabees have avoided being pigeonholed too, Felix reckons. “If we'd had a lot of early attention that some bands had I don't think it would have worked,” he says. “I think every record we've made has been totally different and it's got to the point where people are interested because they don't know what the next Maccabees album is going to sound like.”

It’s the concept of capturing that magic that keeps coming back up as we talk. From the misleading ease of pop music (“If it seems like it’s just fallen out the sky then it seems more... it’s got more,” Orlando says) to the wonder that is Brixton Academy (“A lot of venues in London pop up and go away and become cool and don't become cool but I think Brixton's just Brixton, innit?”) and how differently they find that spark in music as fans. Hugo’s more technical mind breaks songs down into component parts as he listens, while Orlando is a bit more romantic about it and tries to forget he knows the mechanics of how songs are made, and Felix gets starry-eyed about spine-tingling moments watching Jamie T play a certain line live.

Do they think they’ve managed to bottle magic on Marks To Prove It? “We couldn't have made a better record,” Orlando says. “We just couldn't have. We did everything we could. We cared about it massively. We tried very, very hard.”

It might not feel as light as a pop song about a wave machine, but Marks To Prove It doesn’t feel like a slog to me. It feels like staring out of train windows and dancing as a light drizzle slowly dilutes the cardboard cup of lager in your hand. And when you’re colour-coding spreadsheets and endlessly scrolling Twitter at 11am on a Monday morning, there’s a magic in that, for sure.

Marks To Prove It is out now.