Björk steps out as a late-stage dandelion. Her face ensconced in a white pouf; her head could, at any point, fall to seeds and take to the wind. Her modest gown is done in white silk chiffon— an extremely light fabric —but the draping looks heavy, like polished marble.

She belongs in a field, she belongs in the Rodin room at the Met, she belongs as a fiber optic princess wand in a souvenir shop at Disney.

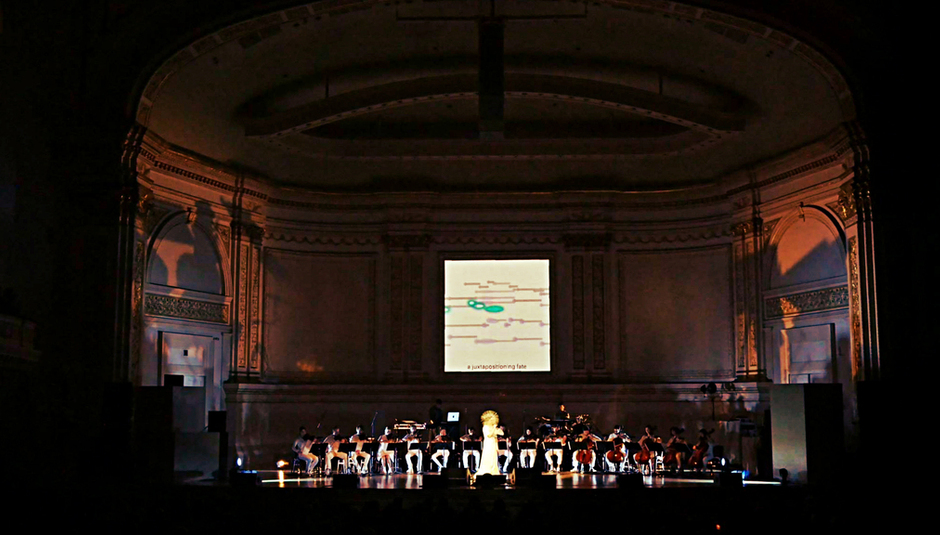

Mostly, she belongs here, front and center at Carnegie Hall backed by members of chamber music group Alarm Will Sound, also dressed head-to-toe in white. Were it not for her co-producer, Arca, and percussionist Manu Degalo, in black and gray, this could pass for a Samuel Beckett recreation of Solange’s wedding.

The stage shimmers under a shifting light, transitioning quietly through each song, from pale pink to blue to a rude, disruptive ochre, all the white fabric quietly submitting to the color imposed upon it.

White comes to the human eye when it encounters all colors of the visible spectrum at once. This is Björk. Material objects that aren’t in and of themselves a light source will appear white if they reflect most of the light that strikes them. This is the orchestra. During the first half of her performance— the first six songs from Vulnicura— she continually turns away from the audience, choosing to give her light to her band.

She leaves her headdress on for the duration, sipping through a straw between songs. Carnegie Hall could swallow many artists, but never her; a white dwarf star is comparable in size to the sun, and it’s light comes from stored energy.

A breakup of this magnitude— so many years together, so much art, and a child— must have been cosmic to live through, sad and complicated and hard to write down and put into an album’s worth of songs. It seems equally torturous to have every single review of your brilliant, gorgeous album contain your ex’s name and hypotheses about the nature of both your relationship and its subsequent implosion. It is a tragedy, and it sucks.

But when she sings, “Maybe he’ll come out of this/Maybe he won’t/I’m not too bothered either way,” all we can really do is shrug in agreement. She doesn’t look at all bothered today. Her power as a vocalist and performer is irrefutable, and with Vulnicura, she’s had time to write, to record, and obviously, to heal. She identifies to us her sense of being ‘one wound’; that is, speaking on behalf of the universal experience of women going through painful separations, like Kim Gordon, who comes to mind as she sings, “I destroyed the icon.” On this record, Björk has, in a way, killed yr idol. As Hazel Cills posited that 2014 was the year of the crazy ex girlfriend, 2015 is shaping up to be the year of the defiant ex-wife, speaking the truth of her experience with men even when it gets reduced (by other women, nonetheless) to revenge.

Hiding her face in monofilament and her skin in chiffon, still entirely present in body and voice, she inhabits a space in performance where she paradoxically seeks and fears intimacy. It’s irrelevant that the dandelion mask mutes her facial expressions. Her body and hands tell her story— that of a woman in a committed relationship with gravity, moving against it in a manner both measured and spontaneous, hands bunching and releasing the fabric of her gown. She sings us around the sharp edges of her miraculous triangle-- father, mother, child-- with an extended pause that hovers in a lonely space between father and mother, keeping mother and child close.

Some people are terrifically afraid of (and confused by) Björk, as she is self-possessed in the purest sense. The recent negative reviews of her MoMA career retrospective seem in line with critics’ reluctance to accept women as both creators and subjects. Her status as the “invisible woman,” largely unrecognized in her role as producer and arranger on her own records, led her to come forward so as not to look like ‘a coward’ to other women, as she notes in ‘Quicksand’ when she reminds us (or herself): “Every time you give up/You take away our future/And my continuity and my daughter’s/And her daughters, and her daughters…”

After a brief intermission, Bjork reenters the theater in a gray and lavender spandex minidress. It is luminous and slightly metallic; armor, reinforced, more so than the white. A bias-cut chiffon cape covers her left side, from her heart, over her back, down to her crotch, wrapping around her in an endless circuit. People in the audience seem so much more likely to cheer when her face is exposed and they can see her reaction. It’s understandable-- she’s beaming. When Arca (who has also made a wardrobe shift, reappearing in a strappy, geometric black halter) cues up her backing vocals, she begins to dance around the stage to the sound of her own voice. The back wall is a twenty foot tall projection of slugs fucking. She looks out into the theater when she cries out, “I am not hurt.” We believe her because we all see it and know it to be true.

Related Reads

1) DiS meets Meredith Graves and names her person of the year 2014

2) In Conversation: Meredith Graves meets Belle & Sebastian's Stuart Murdoch

3) Follow @gravesmeredith on Twitter.

Main photo by Kevin Mazur via Björk's Facebook page.