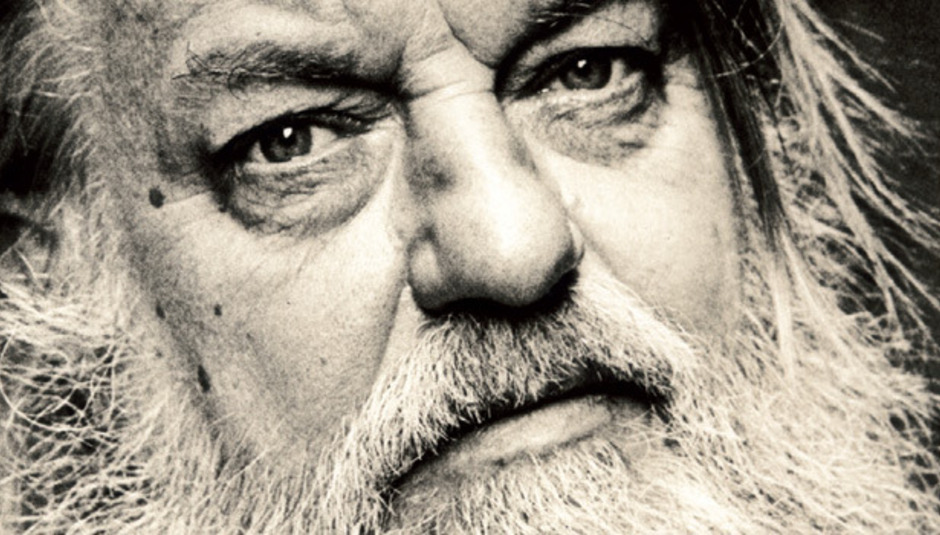

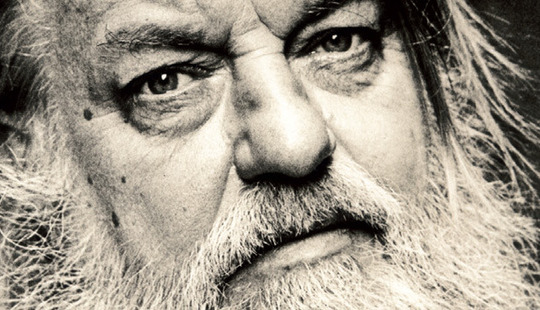

Musically, Robert Wyatt is primarily known in two contexts. Some know him best for the music he released with Soft Machine; one of the leading bands of the London underground scene of the 1960s, they shared a residency at Middle Earth with Pink Floyd and toured America with the Jimi Hendrix Experience. Others, meanwhile, think primarily of Wyatt’s solo releases: the Virgin period in the 1970s, best represented by Rock Bottom, often cited as one of the best albums of all time; the more political Rough Trade period of the 1980s and very early 1990s, during which Wyatt released the top 40 hit Shipbuilding; even the three albums released since 1997, of which 2003’s Cuckooland was nominated for the Mercury prize.

Wyatt has been in a wheelchair since falling from a fourth-storey window in 1973. Unable to operate bass drum and hi-hat pedals, paraplegia also forced a shift from band member and ‘drummer biped’ into solo singer, songwriter and musician. Since Rock Bottom, released the year after the accident, Wyatt has been about as close as it gets to a solo artist. He deploys a wide range of musicians on his albums – from Paul Weller, David Gilmour and Brian Eno to avant-garde jazz musicians like Evan Parker – but only on a track-by-track basis. And he hasn’t played a headline gig since 1974. Rather than a musician, Wyatt likens his existence to that of a painter, the process of private, solitary working epitomised on 1985’s Old Rottenhat, on which he wrote and sang every song as well as playing every instrument.

Painters, however, don’t usually contribute to canvases credited to other painters. Although it’s often forgotten, there’s a side of Wyatt’s discography that is more session musician than solo artist. He has appeared on a surprising number of other people's records – among them, records by Brian Eno, Paul Weller, Björk and Hot Chip. Typically, these collaborations are not equal partnerships, but instead, essentially, a host and a guest; hence Wyatt’s reference to ‘benign dictatorships’. These benign dictatorships make up the second disc of the double-album compilation released by Domino to accompany my forthcoming biography. (Disc one, meanwhile, is an idiosyncratic best-of, going back to Soft Machine and Wyat’s subsequent band, Matching Mole, as well as up to his most recent solo album, Comicopera, released by Domino in 2007.)

A sense of the number and quality of these guest appearances is suggested, perhaps, by the tracks that didn’t make the final list. Wyatt’s vocal on Calyx by Hatfield and the North is missing from the compilation; likewise his keyboards on The Sweetest Girl by Scritti Politti; his singing for pastoral techno outfit Ultramarine; his backing vocals on a radio version of Day Tripper by Jimi Hendrix; his drumming on Love You and No Good Trying from Syd Barrett’s The Madcap Laughs; his looped piano from Brian Eno’s Ambient 1: Music for Airports; his We Love You vocal for Ryuichi Sakamoto; his piano and vocal on Walter And John by Ben Watt; his piano and trumpet for 'Song for Alice', Paul Weller’s tribute to Alice Coltrane. And so on and so on.

What, then, has made the cut? Well, a range of tracks stretching from Venceremos, a Latin jazz dancefloor hit from 1984, to Submarine, recorded for Björk’s all-vocal album Medulla. Other tracks, meanwhile, range from We’re Looking For A Lot Of Love by Hot Chip to Turn Things Upside Down by Marxist big band The Happy End, and from the Latin rock of Frontera, recorded with Phil Manzanera of Roxy Music, to the ECM jazz opera of trumpeter and composer Mike Mantler.

There’s also, I’m both proud and mildly embarrassed to say, a track Wyatt recorded with my band, Grasscut. I didn’t attend the session, since I thought it would be off-putting for Wyatt for his biographer to show up wielding a double bass. (In any case, it is the other half of Grasscut, Andrew Phillips, who does the musical heavy lifting; my own, perhaps slightly curious, role, is to contribute keyboards and double bass, to manage the band, and to help dream up the concepts that frame our releases: the map around a lost village that accompanied 1 Inch: ½ Mile, released by Ninja Tune in 2010, and the remixed tracks hidden in specific locations around England and Wales for 2012’s Unearth.) Anyway, Wyatt contributed piano and scatted vocals to the track Richardson Road, as well as a cornet solo. Andrew phoned me on his way home from the session to say it was one of the finest days of his life, and that he’d never smoked so many cigarettes. We offered Wyatt a fee for his contribution, of course, but he would accept only a hamper of Sussex cheese.

Why, we might ask, has Wyatt collaborated so prolifically? Leaving aside the fact that he is the only musician I know who will accept payment in dairy form, there seems to be no single explanation. One answer is that he actually uses a lot of guest musicians himself – his co-called ‘invisible band’ – and so it is only natural for those musicians to ask Wyatt, in turn, to appear on their own recordings. Another answer is that, almost uniquely, Wyatt doesn’t play live. As a result, he has time for these guest appearances, while peers spend so much time on the road that they barely have time to write their own records, let alone to appear on those by other people. (Arguably, Wyatt’s refusal to perform – the result of chronic stage fright – is also the reason he has remained creative and current in a way that can’t be said of any of his contemporaries, obliged to bash out the greatest hits night after night.)

A third answer to the question of why Wyatt appears on so many records by other people is that he is everyone’s favourite honorary uncle: affable, approachable, and surprisingly accessible for someone who doesn’t tour, let alone tweet. Still firmly on the political left, he is also emblematic of sticking to one’s principles while his contemporaries have tended to shuffle to the right with passing years. This might suggest that some artists see Wyatt, cynically, as a shortcut to credibility. Wife and manager Alfreda Benge – better known as Alfie and herself by far Wyatt’s most important collaborator, as a co-lyricist since 1991 and the artist responsible for all his front covers since 1974 – is certainly aware of this danger. But the large majority of invitations to collaborate, I am sure, come not from musicians hoping some of Wyatt’s credibility might rub off.

Instead, and I think this must be the most important reason for the sheer number of benign dictatorships, the primary motivation must, I believe, be musical. There’s a conversational, offhand quality to Wyatt’s delivery that can be mistaken for amateurism, especially given that he remains relentlessly self-deprecating in interviews. But if his records feel unpolished, even unfinished, it is entirely deliberate. In interviews for the biography, numerous collaborators commented on Wyatt’s tremendous musicality, evident, for instance, in the sheer range of collaborations discussed above. His guest appearances find him contributing, variously, vocals, percussion, keyboards, trumpet and cornet – and across wildly disparate genres too. Crucially, Wyatt combines this versatility with an utterly singular and distinctive musical identity. His singing voice, most obviously, sounds reedy and rickety yet is, in fact, carefully calibrated in both pitching and delivery. The same could be said of his instrumental work: limited in some respects, certainly, now that his drumming days are behind him, but compensated for by a deep awareness of his own strengths and weaknesses. The art lies in making it seem artless.

Wyatt, who turns 70 in January, says he has retired from music – and there hasn’t been a solo album since 2007. The collaborations, though, keep bringing him back into the studio: most obviously For The Ghosts Within, the trio album he released in 2010 with saxophonist Gilad Atzmon and violinist Ros Stephen, but also on less high-profile projects with the likes of Lo’Jo, Ian James Stewart and Gerald Clark. Rumour has it there’s another Phil Manzanera project on the horizon too. Just when he thinks he is out, it is the benign dictatorships, as Michael Corleone almost put it in The Godfather Part 3, that pull him back in. For that, alone, Wyatt fans should be grateful.

Different Every Time: the Authorised Biography of Robert Wyatt by Marcus O’Dair is out now via Serpent's Tail. An accompanying compilation album, also entitled Different Every Time, will be released by Domino Records on 17 November. Marcus is also appearing in conversation with Robert at the Queen Elizabeth Hall in London on 23 November, as part of the London Jazz Festival.

Signed limited edition prints of the artwork for two of Wyatt’s solo albums, Rock Bottom and Ruth Is Stranger Than Richard, are available at www.hypergallery.com.

Grasscut’s cover of Wyatt’s Catholic Architecture is out now on Lo Recordings.