Multiplexes are rarely without one, but the common, garden-variety reboot hasn’t been so prominent a presence in videogaming as it has on the silver screen. Yet 2013’s first quarter has produced two standout examples of developers pressing stop, rewinding, and starting essentially from scratch. Massive franchises rethought, restocked, and released, rightly, to some glorious acclaim.

Of course, neither DmC: Devil May Cry nor Tomb Raider are especially revelatory for taking their respective series’ lore to points of origin. This is a plot device so well used in fiction that it’s right up there with the it-was-all-a-dream angle, utilised when characters have become so dyed in the wool that to shift audience perceptions of them necessitates substantial dramatic license. And not always with successful results.

But the two games do follow a couple of relatively recent reboots of impressive quality. 2010’s Castlevania: Lords of Shadow set about retelling the Belmont’s generations-spanning tale, consigning the likes of Symphony of the Night to a parallel continuity of no consequence to what is to follow (most recently the 3DS-exclusive Mirror of Fate; a proper sequel to Lords of Shadow was announced at last year’s E3).

Last year, XCOM: Enemy Unknown was pitched as a remake of 1994’s UFO: Enemy Unknown; but that translates as a reboot to me. Hugely acclaimed, XCOM has set something of a Metascore standard for any current-generation reboots to follow it. The bar is incredibly high.

That both Crystal Dynamics’ Tomb Raider and Ninja Theory’s DmC come close to matching the magnificence of XCOM is, frankly, remarkable. It’s certainly unexpected, despite the pedigree of said developers. Inarguably, both series had been trading in diminishing returns until these vital rebirths.

The new Lara: an against-the-odds survivor, rather than an obvious sex symbol...

The new Lara: an against-the-odds survivor, rather than an obvious sex symbol...

As much fun as Devil May Cry 4 was – a lot, since you asked – it was essentially more of the same with some present-gen window dressing (and the addition of Nero, who has clearly been an influence on DmC’s newly designed Dante). The last truly indispensable Lara Croft-starring game, meanwhile, was probably the PlayStation’s Tomb Raider II, released in 1997. To say her return to videogame icon from unlikely sex symbol, all flat textures and pointy tits, has been overdue is an understatement.

The new Lara is unlikely to be pinned on many teenagers’ bedroom walls for her looks. Hers is a handsome character model for sure, but the events of Tomb Raider leave Lara bruised and bloodied, windswept and half-starved. By halfway through she’s tumbled down enough terrifying gradients to give vertigo-suffering players nightmares for a month, been strangled to death a handful of times (if you’re slow on the QTE prompts), and is probably suffering from exposure.

Soon enough she’s wading through putrefied pools of blood, slicks of stinking sewage, and sometimes both at once. By the time her face surfaces from the refuge of a deep puddle of the red stuff, visually mirroring Martin Sheen in Apocalypse Now (1.10 into this clip), there’s no doubt: if you find this sort of thing sexy, something’s very wrong with you.

Questions might have to be asked, too, of the Crystal Dynamics team members whose responsibility it was to animate Lara’s deaths: most are grizzly, some more deliciously than others. On a normal-difficulty playthrough, my Lara fell foul of a fair few traps and on-rails obstacles.

One time, a rope snare caught our protagonist’s ankles, lifting her high into the air as enemies closed in. You’re automatically prompted to use a handgun to pop their skulls; but I missed one, and one slit throat later (Lara’s, not his) it was time to try again. Later, cascading rapids need to be navigated – easy enough if it wasn’t for the massive spikes everywhere, most of which managed to spear poor Lara’s head. Gurgle, splutter, die.

The latter sequence becomes a painful memory test – lean left here, right there, use your shotgun to blast through that barrier, and crash back onto dry(ish) land. As such it briefly suspends the disbelief that quickly consumes the player during Tomb Raider, as this is a title that goes out of its way to envelop you in its meticulously detailed environments, its real-world physics, its barbaric violence.

From 14.30: that rapids death in all its gruesome glory

Everything feels palpably real, from the rocks you clamber over while stalking deer, to the smashed-to-pieces aeroplane that chases you down the side of a mountain. So to be yanked from the fantasy to repeat a one-mistake-and-you’re-toast section, even though it lasts mere seconds when successfully completed, is disappointing.

But not so disappointing that you don’t persist, that you don’t push yourself to see what comes next. It’s a design misstep, but a tiny fault in a game that is otherwise, genuinely, wonderful. Some will bemoan its progression into standard third-person gunplay; but even that is masterfully managed by Crystal Dynamics, set pieces orchestrated with cinematic flair and destructible cover rarely feeling like it’s there simply to telegraph the imminent triggering of a Gears of War-style face-off.

Besides, you don’t always have to take the all-guns-blazing approach: the first weapon Lara acquires is the bow, and with arrows a lot quieter than rifle shells, this becomes the most useful tool in your inventory, as effective for stealth kills as it is from-afar headshots.

And nor do you have to follow a prescribed route through the environmental hubs that, combined, make up the playground that is the island kingdom of Yamatai. A real-life country of ancient Japan whose precise whereabouts is both the subject of ongoing debate and the catalyst for landing Lara and company – the crew of the Endurance – on its shores, Crystal Dynamics have positioned Yamatai within the Pacific’s Devil’s Sea, or the Dragon’s Triangle, an area south of Japan that is the region’s equivalent of the Bermuda Triangle.

Their vessel is not the first to have been smashed by its raging seas, Lara coming across an 18th century Portuguese galleon; and exploration of the island reveals downed, decayed World War II fighter planes – bear in mind that Iwo Jima is not so far south, as the albatross flies.

Each hub, connected to the next and opened to fast-travel access once discovered, presents a variety of challenges. On a first playthrough there are enemies, armed usually and always with bloody murder on the mind. Return to these locations once threats have been nullified, though, and exploration becomes the name of the game – scattered everywhere are boxes of salvage, essential for building XP to spend on upgrading equipment, GPS caches, artefacts and (audio) logs offering background on both the island’s inhabitants over the years and Lara’s own colleagues’ feelings.

Survival Instincts mode – trigged by the left bumper on the 360 pad – highlights these collectibles as glowing targets, against background grey. This appropriation of Arkham Asylum/City’s Detective Vision proves useful for spying hidden, or distant enemies, too.

The mix of third-person combat, exploration and gymnastic traversing of environments is generally well polished throughout, with no one section outstaying its welcome, and battles are balanced so that just when it seems Lara can’t take another wave of enemies, another doesn’t come. Instead, silence descends and bodies can be checked for more XP, and valuable ammunition.

If this is a life on the ocean waves, you can keep it...

The story, written by (daughter of Terry) Rhianna Pratchett, does what it can to make returning to certain areas of the island relevant, and fairly skilfully turns what’s initially an against-the-odds survival tale into one of rescue, revenge and redemption, stirred into a gumbo of mystical hokum concerning the sun queen Himiko, long-dead ruler of Yamatai (and who you do find on a rare main-plot diversion into a tomb, looking a little past her prime).

It’s worth mentioning that tomb raiding itself is, mainly, presented as an optional side-quest – you needn’t explore any of these puzzle sections until after completing the campaign, but doing so rewards Lara with a healthy dollop of XP. She even says, at one point, “I hate tombs”… not for much longer, young lady. There’s mention made of her family heritage, how being a Croft will be enough to pull her through. It’s all decently orchestrated, and compelling enough; but the thrills come from the gameplay itself, which is exactly how it should be.

Take the visual sheen off the island landscape and the character-model animations, get another actress to play Lara who isn’t the equal of the really-rather-excellent Camilla Luddington, a graduate of Grey’s Anatomy and seen on US screens playing the Duchess of Cambridge, and still Tomb Raider would be worthy of your money. It’s a triple-A game of both engaging immediacy and substantial depth, a pleasure to experience even after the plot’s been played through to conclusion.

Once everything that can be collected has been, though, there’s not much to keep you returning – multiplayer (untested by me) is apparently underwhelming. But like Grand Theft Auto IV and Arkham City before it, Tomb Raider had me striving for 100% completion (as yet, unachieved). A rarity, indeed, and indubitably a sign of quality software.

Sure, Dante's a dick to begin with, but you quickly come to like him

Sure, Dante's a dick to begin with, but you quickly come to like him

DmC also allows the player to return to its levels – wholly standalone affairs, not presented in an ‘open-world’ layout – once the plot’s finished; and, like Tomb Raider, only permits access to certain secret areas once the corresponding equipment is found to gain entry. With Tomb Raider this can be rope or fire arrows – fairly standard gear for anyone in Lara Croft’s boots. For Ninja Theory’s re-suited-and-booted Dante, though, the tools of his trade are rather more… supernatural. As befits a half-devil, half-angel nephilim with a penchant for massive edged weapons.

Dante’s debut, in 2001’s first Devil May Cry, came at the dawn of last-gen tech, the game quickly becoming a celebrated cornerstone of many PlayStation 2 collections. Originally conceived as an extension of the Resident Evil brand, directed by Hideki Kamiya (now of Platinum Games – more on them, later), Devil May Cry bore some aesthetic and gameplay ties with preceding Raccoon City adventures. But the focus on stylish combat, and the rewards earned by doing away with adversaries in over-the-top ways, pulverising helpless NPCs before delivering deathblows, immediately set it aside from its Resi roots.

Just as the first Devil May Cry scored your battles – successful ones, anyway: die and you start again – so does DmC, with the familiar rankings ranging from D if you truly suck, or simply hammer away at buttons without acknowledging combo commands, to triple-S, reserved exclusively for players who mix up their attacks across myriad enemies, flow smoothly from defence to offence, and avoid taking damage. Complete the campaign with a bunch of B grades and you can replay levels to improve your overall score, as well as unlock achievements.

On, and ahead of, its January release, DmC was shot down by long-term (read: blinkered) Devil May Cry fans, who used several online forums to vent their frustration at simplified combat and both the visual design and personality of the new Dante. Oh no, he’s got dark hair! He swears a bit and likes getting laid! It’s just a button-masher! That female AI colleague is just going to get in the way!

Well, quit your whining, fanboys – this is a reboot remember, and by the time Dante’s seen off the biggest of DmC’s big-bads, there are silver flicks appearing in his locks. Clues are provided throughout the game as to how he’s going to evolve into the character familiar to players of earlier Devil… games; at one point, a wig falls onto his head, its strings falling across his face. Yes, you freakish geeks: Ninja Theory is having fun messing with you.

Dante shows off his mop-top... passes for now

As for how he’s voiced: at the outset, yes, Dante is a prick. But there are reasons why, made clear as the Alex Garland-supervised plot progresses (decent, but anyone who’s seen They Live will notice similarities which, surely, can’t be coincidences), and he does become a likeable protagonist. Some lines are stiff, profanity used for the sake of it; but over time humility and humour becomes more commonplace.

Said AI companion, Kat, isn’t as tied to the gameplay as Trip was, the lead female character of Ninja Theory’s last game, Enslaved, but what misfortune befalls her directly influences Dante’s course of action. The two become close – not inseparable, yet, but there are notes of a budding relationship. Raw aggression is deftly balanced with rawer-still emotion, Dante torn between duty and friendship on more than one occasion.

But it’s probably fair to say that few remember Devil May Cry games for their plotlines. And while great effort has gone into making this retelling of Dante’s initial realisation of his powers and potential an experience that can be watched over a player’s shoulder with some magnetism, it is the hyper-kinetic combat that proves its key attraction.

Initially a straightforward brawler, Dante set upon by generic enemy types that can be done away with using traditional swings of his famous sword, Rebellion, and bursts from his Ebony and Ivory handguns. Once they’re felled, progression to the level’s next encounter is opened – when in combat, a force field traps Dante with his assailants, as per previous Devil May Cry titles and another great Kamiya game, Okami.

But get a little way in and there’s a twist: enemies come in different colours, red or blue, and can only be struck by corresponding angel or devil weapons. What was previously a case of simply linking a handful of muscle-memory combos together becomes a far more strategic experience. Angel weapons, activated by the left trigger, damage blue enemies; devil weapons, on the right trigger, red enemies. New moves, unlocked by collecting orbs for spending between levels, add to the range of attacking options available to Dante.

A handy combat overview from Capcom

Sounds simple? It’s easy enough until you’re facing a veritable swarm of baddies, blue and red, some airborne and some shielded, a few with punishing projectile weapons. You really have to focus on the most dangerous types first, doing your best to avoid the attentions of smaller, but certainly pesky, nasties. Different weapons – you’ll eventually unlock a very impressive arsenal – are quickly switched using the d-pad, meaning that combos can be maintained while alternating Dante’s offensive equipment. And when things get too hectic, there’s always the Devil Trigger to employ, assuming its fully charged: immediately, foes are lifted into the air, helpless, and Dante’s health recharges while his attacks become stronger. It’s a powerful aid, when used properly – waste it, and the tide of battle turns sharply.

Failure in combat is not Dante’s most common undoing here, though. Unfortunately, DmC falls foul of the not-doing-3D-platforming-well sickness that plagues so many post-Super Mario 64 releases. Dante has two grappling hooks at his disposal, one of which lifts him towards a target, and the other draws whatever it’s attached to towards him. These are used to traverse sections without reliable flooring – but getting your left and right triggers confused, not to mention how they’re combined with the face buttons, always results in a death plummet. Just jumping from A to B can be an arse, too, but never as frustrating as sections of, for example, 2011’s gameplay-comparable El Shaddai: Ascension of the Metatron.

Like El Shaddai, DmC uses its visual clout to keep the player engaged, however many times they miss a target and repeat a section. This is a gorgeous game, which uses the Unreal 3 engine in ways that most developers just can’t realise. Splashes of brilliant colour bring the worlds that Dante explores – the real world and its mirror image, Limbo (literally reflected, and brilliantly so, during a prison-set level) – to life with dazzling results. BioShock Infinite is probably the only other title that comes to mind in terms of 2013 games really pushing Epic’s now-creaking engine, revealed in 2004 and first used on a console with 2006’s Gears of War. It’s amazing to compare DmC’s vibrant visuals with the drab greys and greens of Aliens: Colonial Marines (reviewed in the last column), which utilises the same under-the-hood development tool.

DmC’s club-set level is a visual delight, and the music from Noisia and Combichrist fits perfectly throughout, raising the pulse in battle situations (video contains spoilers!)

It’s not the first time Ninja Theory has dressed one of its titles to the nines – Enslaved, terribly under-appreciated though the 2010 Andy Serkis-starring third-person platformer remains, was a delight to drink in, its luscious visuals as much a character of the game as Monkey, Trip or Pigsy.

That game’s simplified combat, effective though it was, has been super-amplified for DmC, though: with Capcom looking over its shoulder, Ninja Theory has implemented a system that consistently hits sweet spots, the sparks that fly every bit as beautiful as those witnessed when Monkey tore his robot adversaries to pieces. It’s complex without being tedious; you needn’t have a mathematician’s brain to calculate the best strategy for advancement, but it nevertheless challenges you to approach each situation freshly, assessing it fully before ploughing in with sword, axe or scythe readied.

It’s Capcom, too, that has helped shape this new, controversial (but surely not for much longer) Dante. Certainly this is true of the new combat mechanics, the visceral bloodlust on show. Producer Hideaki Itsuno told Edge (in issue 248) that “the new Dante is a natural mixture of the previous Dante and Nero”. Nero, of course, was rather more outwardly aggressive than Dante in DMC4.

In the same issue, the game’s chief creative director Tameem Antoniades told the magazine: “(Capcom) worked with our designers directly, imparting the crown jewels of their knowledge, their philosophies.” It shows. The history of the Devil May Cry series is respectfully shaken up, under the supervision of its originators. Their involvement, as publishers, is a seal of guarantee: this is still their baby, and it’s been delivered to the very highest standards.

Spend a little time with the new DmC and it’s clear that it borrows a trick or two from Platinum Games’ Bayonetta. And why not? It’s the hack-and-slasher against which all that have followed have been compared, its plaudits stacking to dizzying heights (IGN 9.5/10; Edge 10/10; Famitsu 40/40). But the Devil May Cry series could be seen as a forefather to Bayonetta: after all, its director helmed the very first Dante-starring romp, namely our friend Mr Kamiya. Their bloodline is shared. But a series few would have expected to embrace the stylish, almost balletic violence of these games is Metal Gear… And yet, it has. Sort of.

Raiden: when that eye of his glows red, you'd better be somewhere else

Raiden: when that eye of his glows red, you'd better be somewhere else

Metal Gear Rising: Revengeance is not a reboot, strictly speaking. But after previous games’ focus on stealth, this being the ninth in the Metal Gear series, its gleeful gallop into frenetic swordplay entirely comparable with DmC is surprising indeed. It’s a dramatic reinvention of the Metal Gear brand, hence its inclusion here. It hits harder, it looks better, and it moves faster than ever before… but is it any stronger than its immediate plotline predecessor, the ageing Snake’s swansong Metal Gear Solid 4: Guns of the Patriots?

When the Platinum logo appears on screen, you’re guaranteed amazing combat, and Revengeance – yes, it’s a stupid title; the neologism department at Konami was having an off day – delivers some truly breathtaking moments of cyborg-on-cyborg action. You play as Raiden, introduced way back in Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty (remember that controversy? Makes the fuss over DmC look like spilled milk) and today more machine than man – especially when he loses an arm early into Revengeance. It’s okay, though, because he’s got some new friends, and they patch him up a treat. He’s got a metal chin these days, too, and Platinum never misses an opportunity to show it grazing against something in a cut scene.

The problem is that there’s simply not enough of Revengeance. It is such a fun game to play – controlling Raiden is a dream, once you’ve figured out how to pull off parries correctly at least half the time, and the environments, while not the most inspired to grace a third-person affair like this, are full of opportunities to use the new Blade Mode. When activated, with a tickle of the left trigger, Raiden can direct a swing of his blade in any angle he pleases, directed by the right stick. Trees, lampposts, advertisements, fences, cars, crates: slice and dice them until your heart sings out in joy.

It’s helpful, too, for dissecting enemies – and you’ll need to do so, as Raiden’s health and fuel cells (needed for Blade Mode) can be recharged by swiping electrolytes from opponents’ insides. Sounds gruesome, but once you’re used to it, this ‘Zandatsu’ move becomes second nature (assuming you can tolerate repetition of the two quips he’s got for successfully executing the move).

Blade Mode and Zandatsu, in detail

Truth be told, you won’t be hearing them for long. On a first playthrough – on easy mode, not seeking out every bonus virtual-reality training exercise or fellow-hiding-in-a-box, and ignoring the codec conversations entirely (apart from saving) – I finished the game in a shade over four hours. This figure doesn’t include cut-scenes – there’s a lot of them, this being a Hideo Kojima(’s Kojima Productions development studio) production, especially during the game’s final third – and does, of course, represent a run where enemies are rather keener to fall over than not. But still: it is an almost worryingly short game.

Producer Atsushi Inaba has expressed dismay with criticism of the game’s length, but even on the next difficulty up, finishing the game in under six hours is easily achievable (more deaths, a greater emphasis on collectables). Again, this is in-play time only – forget the preamble, the credits, etc. And the quality of the gameplay is extraordinarily high. But some potential buyers will, nevertheless, be put off by Revengeance’s limited shelf life.

I know, I’m playing it wrong: Metal Gear games are supposed to be tackled on the hardest settings. I know, I get it. Sorry, I wanted to see my way through the story so that I could write about it. But now I’ve finished Revengeance, I’m still not entirely sure of what’s happened. It helps to be familiar with the Metal Gear plot to this point – this point being four years after Guns of the Patriots, the year being 2018. But if you’re not: five years from now, it seems that everybody’s still crippled by the recession, Pakistan is a fine place for terrorists to scheme, and warfare makes a nefarious band of ne’er-do-wells whopping fistfuls of filthy lucre.

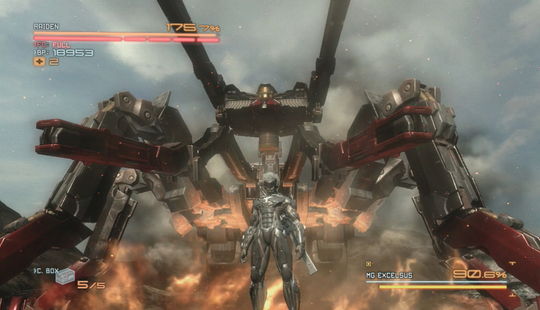

Truthfully, the reason why Raiden’s in South Asia chopping the legs off a massive mechanical spider thing doesn’t matter: there’s a massive mechanical spider thing right there, go and chop its legs off. And before that point in the game, loads of biomechanical brutes show up to be slaughtered. Some manage to kill Raiden, but that’s okay – pick yourself up, try again, remember to parry. (Please, remember to parry, or we’ll be in the Badlands all week.)

Massive mechanical spider thing: it's behind you

Massive mechanical spider thing: it's behind you

Seriously, it’s not really stressed at the game’s outset, but parrying enemies’ attacks is vital, especially in the game’s later stages. Raiden in full flow is a monster, and this is made especially clear when he learns Ripper Mode (it’s DmC’s Devil Trigger, kinda – attacks are more brutal, everything turns red). But he’s not invincible, and will crumple with no little regularity unless you understand that defence is just as valid a form of attack. Come the final boss battle proper, it’s almost all you can do – at least until a (not entirely unforeseen) twist, when an old adversary turns out to not be such a bad egg after all.

Revengeance is a brilliant game: forget the story as it’s the action that counts, and it’s incredibly strong in this respect. The marriage of Kojima Productions and Platinum Games is one that, one hopes, will be repeated – a sequel is already rumoured. The stealth of previous games isn’t really missed – there are token nods to that style of play, but it’s more fun, usually, to alert enemies to your position and lop their limbs off. But it is short. You can, like DmC, and Bayonetta, replay levels to improve your ranking (battle points won for style and speed are exchanged for upgrades). There are numerous VR missions to complete if you’re aiming to 100% the experience. And it is a game that, with the difficulty ramped up, makes no attempt to hold the player’s hand through its campaign – blink, and you’ll probably die, and that’s on the first level.

But there’s no getting away from it: for the hours you’re likely to spend with Revengeance, don’t part with too much money. It is too good to be missed, but only at a price that you feel best reflects a solid weekend’s play time.

(All games played/tested on Xbox 360.)

DiScuss: What old games, collecting dust amongst your collection of 8- and 16-bit cartridges, would you love to see rebooted in this, or the next, console generation? I'm tempted to turn a mind to Road Rash... but what developer would be ideal for it?

NEXT MONTH: We're off to Infinite(y) and beyond with an overview of BioShock's twin cities of Rapture and Columbia, and an exclusive conversation with series creator Ken Levine.