“I wrote my mother, I wrote my father, and now I’m writing you too. I’m sure of mother, I’m sure of father, and now I wanna be sure, very very sure, of you...”

'Don’t Sit Under the Apple Tree', taken from The Master OST.

A palpable sense of underwhelment wafted over the Odeon West End audience, sparse as it was, when the end credits finished rolling and the lights came up after the 70mm preview screening of The Master. The two friends I was sitting with seemed distinctly unimpressed, and disheartened critiques, admonishing it for not being cinematically equivalent to to Paul Thomas Anderson’s earlier output like Magnolia and Punch Drunk Love flowed freely. I stayed quiet and listened mostly, offering tepid counterpoints, referencing a few scenes that stuck out to me as being unequivocally brilliant, but not really challenging their assertions because, as much as I wanted to like it, the reality was that I thought maybe I agreed with them. Maybe The Master was...boring.

To spin a Martin Luther King Jr. quote on its head, no, The Master is not filled with the same fierce urgency of now that propelled Anderson’s earlier films. But one of the reasons why there's so much anticipation around a P.T. Anderson film before its release is because we know he isn’t a by-the-numbers filmmaker. There is no formula in style or dramaturgy connecting Punch Drunk Love with There Will Be Blood. There is no single vision of the world. The brutal and earth-shattering cynicism displayed in Boogie Nights is equally counterweighted by the soft, quiet resilience and subdued hope of Magnolia. Anderson, unique among his generation, is a talent whose gift it is to storytell in the most classical tradition.

Which brings us back to The Master. A film that I’m now convinced - little more than a week after watching and grappling with it - is the year’s best.

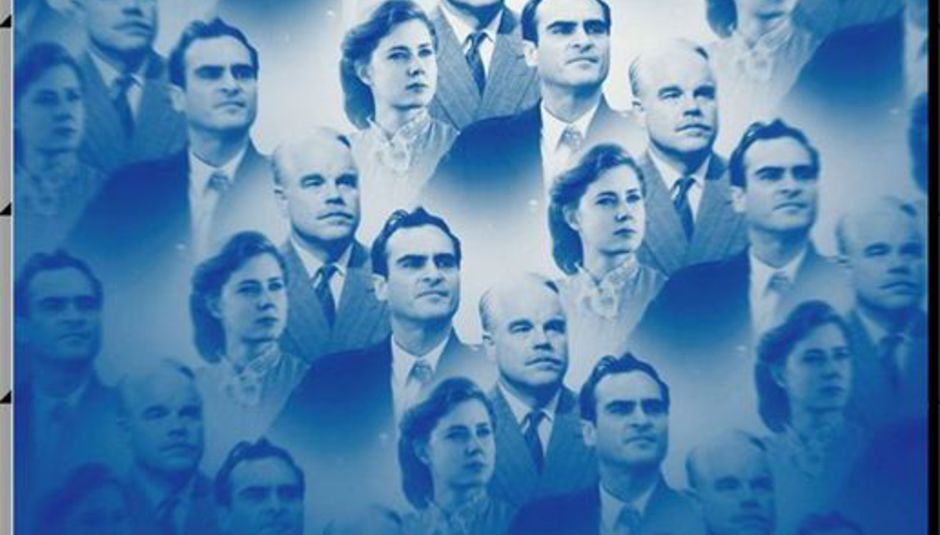

No, it doesn’t tell an exciting story. There isn’t really very much of a story at all. It isn’t even really a character study - character studies slowly peel back the layers of their protagonists, pushing you deeper and deeper into their psyches and forcing plot points and reveals through this process. Everything we need to know about each and every character in this film is presented to us when we first meet them. In fact, the key centerpiece relationship at the fore of the film, between Lancaster Dodd (portrayed with a ferocious zeal by Philip Seymour Hoffman in the best performance of his career) and Freddie Quell (a lurid and tormented performance by Joaquin Phoenix), is static and almost maddeningly unchanging for the duration.

Anything less than this approach would have been dishonest. Dishonest to the viewer, dishonest to the characters, but most importantly, dishonest to what the film is about in the first place: It is not about the leader of a burgeoning cult as appears on the surface but rather about submission and domination, revolt and prepotency.

What Anderson achieves in refusing to allow the film any arc amounts to the most singularly devastating and enlightened meditation on the human condition’s need for both of these things that cinema has offered us in many years. What at first seemed like subdued disappointment, at not being sure what the point of it all was, was actually the point.

Like Pasolini’s Salo: 120 Days of Sodom, Bergman’s Persona, or Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc, The Master quietly devastates us with its matter of fact and almost clinical portrayal of the horrific banality of how we dominate and subjugate one another.

Far from freeing Freddie Quell, Lancaster Dodd locks Freddie into the cycle of barbarism and ignorance which he first fell into during the War. But there is no force here, not even a hint of brainwashing. Freddie knows the Master is peddling bullshit - he says as much numerous times throughout the film - but that’s beside the point for Freddie. The Master isn’t interested in making Freddie better. If he were, he may have heeded the numerous interventions of his wife, Peggy (Amy Adams) who repeatedly chastises her husband by telling him “this is pointless. He isn’t interested in getting better”. Of course not. He is interested in facilitating Freddie Quell’s madness and perpetuating it. We are left to assume that this is why Freddie keeps returning, time and again, to his Master’s heels, whereas he held nothing but contempt for and actively fled the psychologists and therapists the Navy had offered him. If the Cause actually fixed people, there would be no more reason for them to be part of it.

One of the most remarkable scenes comes towards the close of the movie. With no stated reason, Dodd decides to bring Quell, his daughter, and his son-in-law to a desolate, dried out flatland with nothing but a motorbike and a high-speed run on it to aid in spiritual development. Dodd goes first, camera tracking from the side. He leans forward as the motorbike speeds ahead, as though he were hoping for a vortex to appear and transport him to another world if he could just gather enough speed. It’s a moment of beauty and of sheer cinema. Next, Dodd instructs Freddie to hop on and focus on a point in the distance and drive to it. Freddie does, and he disappears over the horizon. And there is nothing. For quite some time. Freddie’s gone. Except he isn’t. In the next scene (which takes place significantly later), we discover not much has changed, and his pull to be with the Master is as strong as ever.

The result of all of this is a disquieting portrait of human co-dependency. It’s a theme Anderson has visited in all of his films, but has the ultimately the most ravaging effect here. The Master is a film that refuses to leave you, seeping into your subconscious the way that Dodd does with Quell. It stays with you long after the film has finished, lingering, diminishing your trust in your own ability to self determine a destiny. It’s just as Dodd preaches to his disciple: “If you figure out a way to live without a master, any master, be sure to let the rest of us know, for you would be the first in the history of the world.”

The Master is at cinemas now.