“If you love music, this is the place to come,” said Mikolaj Ziolkowski, the chief organiser of Heineken Open’er. We were sat backstage in a tent on the disused military airport in Gdynia, northern Poland, where his festival takes place. “Our audience prepare for the festival,” he continued. “They listen to the music and care about who’s playing. There are not too many drunk people, as you can see. It’s not a holiday, it’s a music festival.”

I smiled and nodded, but inside I was thinking: “I’m not sure this will play well in Britain.” Do people who go to festivals want to be told to take things more seriously? I’ve been to British festivals and we’re just inefficient machines for converting gallons of booze and fistfuls of drugs into piss and shouting.

At Open’er, they only serve Heineken. Aside from a couple of stalls offering Desperados as an alternative beer, it’s the only alcohol on site. As a branding exercise it seems utterly self-defeating. After four days of nothing but Heineken you don’t want to taste another drop. It’s hard to get raving, stumbling drunk without hard liquor, but naturally we in the British Music Press Corps gave it a damn good try. Must be all that Olympic spirit. Inspire a generation.

Still, Mikolaj had a point. Open’er’s unusually attentive 65,000-strong audience and thoughtfully curated line-up combined to produce some jaw-dropping moments. They served up everything from Björk firing up her overhead Tesla coil to an epic six-hour production of Tony Kushner’s ‘Angels In America’ in the theatre tent. They also provided one of the most brilliant, unique and aggressively weird things I’ve ever seen on a festival stage: the hour-long orchestra performance of work by both legendary radical Polish composer Krzysztof Penderecki and Radiohead's Jonny Greenwood, his devoted acolyte.

We had landed in Poland early on the Wednesday at Gdansk’s airport, which is named in honour of Lech Walesa. The baggage handlers all seemed to wear approximations of his walrus moustache, hairy personal tributes to the shipyard union leader who in 1990 became the first Polish President elected by popular vote and oversaw the country’s transition out of communism. I had a hunch that meeting Penderecki would help me to understand how music and culture had interacted with the country’s historical realities, but first there were bands to be seen.

We arrived on site in time to witness The Kills in indomitable form. Every eyeball on site seemed to be trained on Alison Mosshart, her hair dip-dyed like a tequila sunrise, as she elegantly stalked the stage. The band were backed by four extra drummers, wearing red bandanas, and their contribution made tracks like ‘Heart Is A Beating Drum’, ‘Fuck The People’ and ‘Monkey 23’ sound imposingly huge. They’re not shy about their influences, with ‘DNA’ sounding uncannily like The Rolling Stones’s ‘We Love You’, but nobody cares. When everyone else leaves the stage to let Mosshart and Jamie Hince tiptoe through ‘The Last Goodbye’ the crowd is rapt. The only bum note is Hince’s Polish, which needs a polish. “Cheers!” he shouts at one point, “What do they say in Poland?... Cheers!”

Björk’s Polish is better, and she thanked the crowd regularly: “Dziekuje!” She’s played here before, in 2007, and seemed to be welcomed back as a returning hero and kindred artistic spirit. She was very much in Biophilia mode, with exactly half of her 16-song set drawn from that most recent record. The Tesla coil suspended above her sparked into action for ‘Thunderbolt’, while both ‘Crystalline’ and closer ‘Declare Independence’ turned into onstage raves as she was joined in losing the plot by her army of backing singers.

New Order opened by saying sorry. “This is our first time in Poland,” Bernard Sumner announced. “We can only apologise for not coming here in the last 30 years. It wasn’t our fault.” No matter, they still manage to somehow sound ahead of their time despite Sumner’s ragged vocals. Tracks like ‘Regret’ still sound transcendent, and ‘Transmission’ and ‘Love Will Tear Us Apart’ aren't a bad couple of songs to keep up your sleeve for the encore.

We arrived the next day to discover that things start late at Open’er. At least we had plenty of time to explore the site. I ate some perogies, which were delicious but so greasy I worried my lips had turned translucent. I visited the fashion tent, where a catwalk jutted out of a hillside bunker. Young Polish designers displayed punk knitwear in garish colours and t-shirts emblazoned with slogans like “Fuck My Polish Life”. Mainly the airport’s old runway was lined with the sort of international hippy tat stalls that you find at every festival in Europe, but the Muzeum, a modern art gallery, is more unusual. Housed in another bunker, it had short art films playing on a loop inside wooden containers. “My ambition is to do art on a high level,” Mikolaj had told me, explaining why Open’er avoids workaday fancy dress festivities. “Usually at other festivals it’s just street theatre as decoration.”

When 5pm rolled around the first bands came on and I went to check out one of the locals. Iza Lach is a much-hyped young singer who's just been signed by the artist formerly known as Snoop Dogg. There wasn’t much evidence of his rap influence, or indeed his new reggae incarnation, in her spikily confident keyboard-led set.

By the time I left the tent 45 minutes later a thick fog had descended which made it impossible to even see the main stage from the press area. With stage lights streaming through the fog as people wandered back and forth the whole scene could have been lifted straight out of ‘Close Encounters Of The Third Kind’. Through the mist drifted the sound of Kapela Ze Wsi Warszawa (The Warsaw Village Band) playing extended versions of traditional Polish folk songs.

Open’er does a pretty great job of balancing intriguing Polish acts with high-end headliners. Justice topped the bill on Thursday night and ruthlessly got every soul moving, while the following night Franz Ferdinand’s dazzlingly tight set was followed by the reformed Cardigans. Everyone fell for the wonderful Nina Persson just as hard as we had done for Mosshart. Away from the main stage, Public Enemy and Janelle Monáe delivered very different but equally energy-packed and rapturously-received sets on consecutive nights. The Mars Volta and The xx closed the final night, both confidently justifying the fact that they played higher up the bill than you’d see them in the UK.

As a booking philosophy, Mikolaj had explained with a laugh that: “Our ambition is to be an interesting festival. We don’t book bands who are very popular but not very interesting.” He’s achieved that goal this year, although out of politeness I didn’t bring up the inevitable Mumford & Sons performance. The Polish summer proved to be just as changeable as the British, and in four days we got everything from sweltering heat to thick fog. The only time the heavens really opened was for a spectacular thunderstorm which delayed the Mumfords. Maybe God was trying to send Mikolaj a message.

By contrast, that remarkable Penderecki // Greenwood performance was fittingly cloaked in mysterious fog. I had to get up close just to see the full string orchestra assembled onstage. The show had been performed just twice before, at the Congress of Culture in Wroclaw, and at the Barbican in London. As Mikolaj explained: “It crosses borders. It’s been performed for classical music fans but it’s never been performed for regular people. It’s never been at a festival. It was an experiment, but it worked! I know that 99% of people won’t be listening to his CD in their cars, but they came with open minds. People who come to this festival should know that this kind of music exists and it’s very important. Penderecki is a big star in Poland, so for him to come here means a lot. He was very enthusiastic to do it.”

The format is that first Penderecki’s startling 1960 composition ‘Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima’ is performed, followed by Jonny Greenwood’s ‘Popcorn Superhet Receiver’, which was heavily inspired by it. Then we hear Penderecki’s ‘Polymorphia’ and Greenwood’s ‘48 Responses to Polymorphia’, which includes echoes of Bach and Messiaen.

It’s strange and unfamiliar music to hear in a festival setting. Many of the audience will have heard Penderecki’s work before, though, even if only in films. He’s appeared on soundtracks including The Shining and a couple of David Lynch movies, while parts of ‘Polymorphia’ feature in The Exorcist. ‘Popcorn Superhet Receiver’, meanwhile, formed the basis of Greenwood’s famous There Will Be Blood score.

Penderecki’s avant garde work came about through his early experiments with electronic music, and he asks the orchestra to do things with their instruments that they’d never usually do. String instruments are transformed into percussion, which lends their whole performance an unusual physicality that complements the often jarring and unbearably tense music. Greenwood goes even further in ‘48 Responses’, and towards the end the violinists swap their bows for pacay tree branches that look like toy swords. At the finale they shake their branches over their heads, creating a sound like massed armies of rattlesnakes. For the entire performance, which lasted over an hour, the audience were flawlessly attentive, something I have to confess to Mikolaj would surely never have happened at a UK festival of comparable size.

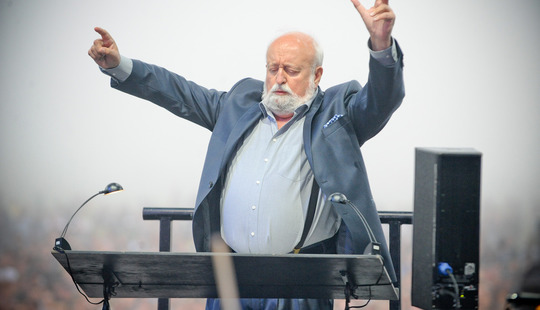

Penderecki conducted his own pieces, while Marek Mos conducted Greenwood’s, who wasn’t actually there. He didn’t need to be. This was Penderecki’s rock star moment. At the end of ‘Polymorphia’ he walked offstage and than returned to yet more whooped applause. He lifted both arms above his head and punched the sky.

“It’s not easy music,” Penderecki admitted when I tracked him down backstage, “but it is music that these young people have never heard before. Those two pieces, ‘Threnody’ and ‘Polymorphia’, I wrote 52 years ago. I was young and enthusiastic. Actually at that time, only young people liked my music. Now it’s finding a new generation.”

I asked him what made ‘Threnody’ so radical, and he replied: “It’s unusual because of this new way of using string instruments, playing behind the bridge or on the tail-piece, different types of vibrato, and so on and so forth. Also, of course, treating the instrument as a percussion instrument. I remember, 50 years ago many orchestras went on strike and refused to play this music, but I believed that I was right. Of course, the string instrument is not built for such music but it can produce a sound that it had not done before. I was happy to be a radical.”

If ‘Threnody’ was radical, then the strange genesis of ‘Polymorphia’ is something else entirely. As Penderecki explained: “I was interested to know the reaction of people to my music. My friend was a psychiatrist, so we played ‘Threnody’ for the sick people, and recorded electroencephalograms. I used the results of this in ‘Polymorphia’. It doesn’t look like a piece of music.”

He opened his book of sheet music to show me. Black lines zigzagged across the page like the medical charts of a particularly unstable patient. Which is precisely what they are. Penderecki chuckled to himself. “You can imagine that 52 years ago, for musicians who had only studied music in a conservatory, looking at this score and the music that I asked them to play was a shock! Even now if somebody wants to play ‘Polymorphia’ or ‘Threnody’ I ask for one specific rehearsal for an explanation of the symbols I have used. Otherwise, you can’t play it.”

Penderecki’s musical experiments seem all the more remarkable when placed in the context of a Poland still living under communism. I asked the composer how his country has changed in his lifetime. He replied: “It’s a different country now to the one that I remember. I grew up under communism. You can compare it maybe to the situation in Cambodia… I’m exaggerating perhaps, but it was a very poor country in Europe and that’s completely changed now. The economy is very good. It is the only country without a crisis. People are working. Everything is possible. There is freedom. When I grew up, sacred music and avant garde music was forbidden because it was the music of the bourgeois. We were very lucky to have the Warsaw Autumn festival, which was the only place where this music was played. Then I started, with other composers, to fight for freedom in art. Poland was a unique country in the socialist bloc where avant garde music was possible. It was not in Russia, not in Czechoslovakia, not in other countries, only in Poland.”

His fight was not just an artistic one but a fight for political freedom. “I wrote a lot of sacred music,” he continued. “At that time it was forbidden but because it was a success in the West they started to play my music in Poland as well. It could not be performed when I wrote it. We had to find private choirs to practice the music. It was 10 years before I saw it in Poland. We did it, really. Artists, not only me, of course, but my colleagues, people like Wajda for movies and Tadeusz Kantor for the theatre. We changed Poland.”

The country Penderecki helped shape is one that embraces the musically adventurous, and there’s no better place to experience that than at Open’er. The crowd are also wilder than Mikolaj made out. On the final night after leaving the site we in the British Music Press Corps ended up in the nearby town of Sopot. Hundreds of Polish teenagers leaving the festival were celebrating their last night, and their freedom from Heineken, by sitting on the beach and mixing litre bottles of vodka and apple juice. I could see many, many drunk people. We were treated to the sight of one of my fellow journalists stripping stark naked and wading out into the water. He splashed around like a wet seal as the sun came up, but even that wasn’t quite as weird or unforgettable as what a 78-year-old Polish composer had just done with a string orchestra, an awed crowd and a head full of twisted, revolutionary ideas.

Photography by P. Tarasewicz.