All of the pieces mentioned in this article can be found in this spotify playlist, for easier navigation.

“Little by little my prejudices against classical music began to fade away ... It came as a sheer revelation to me. It is impossible for me to describe the enthusiasm, the ecstasy, the intoxication which I was seized by.”

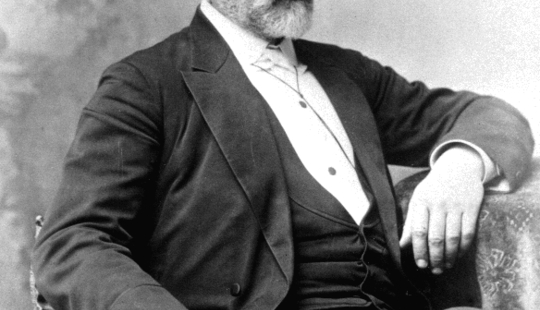

Who said this? From the way things have been going recently, you’d be forgiven for thinking that it was Damon Albarn, who’s just finished his second opera. Or maybe it was Jonny Greenwood, who’s been collaborating with Polish composer Krzysztof Penderecki. Or perhaps it was Owen Pallett, who recently premiered a violin concerto in London. On the other hand, it might have been St. Vincent, who has been known to write chamber music occasionally. Then again, it could have been Elvis Costello, who wrote an entire ballet a few years ago. All of these would be sensible guesses. But, as you’ve probably guessed by now, it was none of those people. In fact, it was none other than Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, who is the focus of this month’s article. As with the previous articles in this series, I’m going to be introducing some of the most important works of this great composer in a way which will hopefully be accessible without being patronising. I don’t come from a classical background (I can’t even read music), and up until a couple of years ago I knew virtually nothing about the subject. I know what it’s like to come to this music without any prior knowledge, and how vast and intimidating the classical repertoire can seem. So believe me when I say this – there are centuries of amazing sounds just waiting to be explored – all you have to do is listen.

In previous editions of The Classical, we’ve been racing around different periods and styles without much sense of the connections between them. So before talking about the music itself, we need to fill in some of the gaps between Beethoven’s death in 1827 and the start of Tchaikovsky’s career as a composer in the 1860s. Beethoven ushered in the new era of Romanticism, where personal expression, rather than the demands of patrons, became paramount. Orchestras got bigger, and the instruments they used became more varied. Composers like Schubert, Chopin, Schumann and Mendelssohn began to explore the new musical vocabulary which had been opened up by Beethoven, while at the same time rediscovering the technical mastery of Baroque composers like Bach.

It wasn’t long, however, before splits began to appear in the German musical community – the so-called War of the Romantics began, pitting “progressive” composers like Liszt and Wagner against the more “conservative” Brahms. The reality, of course, was more complex, but we’ll discuss that another time. Both sides claimed to be carrying on Beethoven’s legacy, but the methods they chose differed. Liszt invented the “Tone Poem” (a single-movement orchestral piece which tells a story) and wrote explosive new piano works while Wagner worked on epic music-dramas. Brahms, meanwhile, reinvigorated traditional forms like the symphony and the concerto. The basic dispute between them was whether music should be “programmatic” or “absolute” – should it try to be like a novel, filled with themes, characters and stories, or should it remain purely abstract and concerned only with its own internal, formal logic?

But that was Germany, where people were sometimes overly serious about music. The situation in Russia was a little different, and so were its musical traditions, which were based on a cappella religious music. The debates happening in Europe were taken up in Russia to an extent, but for many musicians the problem was Europe itself – should Russia try to keep up with development there, or should it forge ahead with its own unique national style? The Rubinstein Brothers, who ran the St Petersburg Conservatory, belonged to the traditionalist, westward-looking camp, while in Moscow a rival group of composers called “The Five” (no prizes for guessing why) were formulating new music with a uniquely Russian flavour, drawing on native composers like Glinka while at the same time looking eastwards for inspiration.

So where exactly did Tchaikovsky fit into this complex situation? Well, the short answer is that he didn’t, and perhaps that’s what makes him so great. There’s a moment in one of Tchaikovsky’s operas where a group of aristocratic ladies take a break from listening to dreary ballads and decide to sing a lively folk song instead. But before they really get going they are interrupted by a stuffy older woman who tells them to stop, and asks them – “are you not ashamed to dance Russian style?”. This brief moment beautifully illustrates the many conflicting forces which influenced Tchaikovsky’s music – high and low, east and west, classical and folk, private and public, past and present, propriety and emotion.

Tchaikovsky studied with the Rubinsteins, but he also knew and even collaborated with The Five. He was also extremely independently-minded, with very particular tastes – he thought Brahms was too serious, but also had very mixed feelings about Wagner, and often avoided the debate between them altogether by opting to listen to French ballet or Italian opera instead. Most of all though, he was obsessed with Mozart – the quote from the start of this article actually refers to Tchaikovsky’s childhood love of Mozart’s opera, Don Giovanni. Tchaikovsky even referred to Mozart as a “musical Christ”. This cocktail of influences made Tchaikovsky one of the most distinctive composers of the Romantic era. His music almost always possesses an incredibly high level of drama and emotional intensity, mixing saccharine sweetness, sweeping grandeur, rococo ornament, patriotic simplicity and, sometimes, poignancy and despair.

As a result of his idiosyncratic approach, the highly sensitive Tchaikovsky received both praise and criticism from virtually all sides, and worked to please himself rather than conforming to any particular school of thought or musical dogma. The fact that Tchaikovsky was gay meant that sadly, for much of the 20th century, many critics derided his music, often basing their reviews on offensive stereotypes and fear of his popularity rather than meaningful analysis. Tchaikovsky’s talent for making an immediate emotional connection with his audience lead to accusations of vulgarity, sentimentality and bombast. His occasional avoidance of some traditional methods of composition, such as development and sonata form, were also highlighted as failings. But where some saw mistakes, others saw originality.

Like Rossini or Johann Strauss II, Tchaikovsky was someone who was unafraid of producing pure entertainment, but also made huge and anguished musical statements. He never shied away from doing something vaguely ludicrous if it achieved the right effect, and he succeeded in capturing the extremes of total love and utter despair in a manner that was entirely his own. His music opened the door to generations of future Russian composers, and also inspired others across Europe to find a balance between national and personal influences.

Tch-Tch-Tch Tchanges

At a time when many composers were choosing to specialise, Tchaikovsky stood out as a musical magpie, flitting between different genres with ease, producing huge quantities of orchestral music, sometimes in traditional, “absolute” forms like symphonies, concertos, sometimes in “programmatic” ones like operas and tone poems, and sometimes in forms which he revitalised, such as orchestral suites, serenades and, crucially, ballets. It makes sense to begin with the tone poems (although Tchaikovsky didn’t always call them that) as they are some of the composer’s most famous, evocative and dramatic works.

First up is the infamous 1812 Overture, which was written to commemorate Russia’s victory over Napoleon. It is a little overblown, and even Tchaikovsky himself thought it was a bit much, with its use of cannon-fire, a chorus, church bells and national anthems, but it is immensely entertaining. You can listen to the whole piece in the spotify playlist at the start of the article, but I think the late, great Ken Russell’s insane film version of the finale gives a better sense of just how brilliantly over-the-top this music is. If you’re interested in the complexities of Tchaikovsky’s private life, the film also provides a wonderfully deranged overview:

If you like the triumphalist tone of that piece, then you may also enjoy the equally explosive Marche Slave, which was written as a kind of pan-Slavic propaganda piece when Russia saw their allies in Serbia being attacked. Next up is the Capriccio Italien, the product of Tchaikovsky’s many visits to Italy as well as his love of the operas of Rossini and Verdi. The piece starts with a huge brass fanfare inspired by a bugle call the composer heard while staying in a Roman hotel next to a barracks. This is followed by a slow, sultry theme until 4:50, when the carnival is unleashed. Then, at 7:20, a new dance emerges. Finally, at 13:40, the carnival march returns in an irresistibly boisterous finale. This version was conducted by Leonard Bernstein, one of Tchaikovsky’s most sympathetic interpreters:

The cult of Shakespeare was huge in the nineteenth century, and inspired a vast amount of music as a result. Tchaikovsky’s love of tragic heroines meant that he was no exception to this rule, producing one of the most famous Shakespearean pieces ever written – The Romeo and Juliet Fantasy Overture. That title might sound rather pompous, but chances are you’ve probably heard the “love theme” extract from this piece countless times in films and adverts. Tchaikovsky wasn’t necessarily trying to tell the whole story of the play, so you don’t have to have read it to appreciate the music. What Tchaikovsky did instead was to conjure up the emotional extremes experienced by the characters, creating clear moments of passion and conflict. At the start of the piece, imagine a sunrise over the city of Verona, until about 5:40, when the Montagues and Capulets come out to fight, and different parts of the orchestra battle for the upper hand. Then, at 7:45, listen out for the seamless transition into the love theme. Over the course of the piece these two themes combine, perhaps suggesting that love must inevitably be paired with conflict and suffering. This performance is conducted by Valery Gergiev, who is a master of the Russian repertoire.

If you enjoyed that piece, then I also recommend listening to Francesca da Rimini, a slightly less well-known but equally masterful tone poem based on a story by Dante about a woman who is cast into hell because of who she loves. Listen out especially for the whirling winds of the inferno, which may have been inspired by Liszt.

Tchai Latte

Tchaikovsky wrote many concertante pieces – works for an orchestra and an instrumental soloist. Some of these are fully fledged concertos, each split into three distinct movements, others take the theme-and-variations form, while some are freestanding works with only one movement. There are also several fragmentary, incomplete or unresolved pieces which come from a fallow period of Tchaikovsky’s life after his disastrous marriage. To keep things simple, I’m going to focus on three of the most important works, but I’ve also included a selection of other worthwhile bits and pieces on the spotify playlist at the start of the article.

Here’s a the first movement of the first Piano Concerto, one of Tchaikovsky’s best-known pieces thanks to its instantly recognisable “power chords” opening. The concerto is made all the more impressive by the fact that Tchaikovsky himself was not a particularly skilled pianist, and rarely used the instrument to compose. In fact, his own teacher Nikolai Rubinstein hated the piece at first, before eventually championing it. Analysing all the constituent parts of this concerto would be tedious, so just listen to the powerful sound of the Berlin Philharmonic, the immaculate playing of Evgeny Kissin and his amazing hair. And if you find the first movement a bit much to take in, try listening to the delicate slow movement instead.

Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto, like those of Brahms, Mendelssohn and Beethoven, is one of the great masterpieces written for the instrument, and is filled with soaring melodies and intensely virtuosic passages. Here’s Janine Jansen giving a spirited performance of the last movement, which proceeds with manic energy.

Finally we reach the closest thing Tchaikovsky ever wrote to a cello concerto – his Variations on a Rococo Theme, which sadly have nothing to do with Arcade Fire. In this context, the word Rococo simply refers to a return to the elegant, refined music of the eighteenth century. Tchaikovsky collaborated closely with a famous cellist of the time to produce this compact, neo-classical piece, which is stuffed with ostentatious solo parts. Here’s Tatjana Vassiljeva performing the piece in full, but if you want to skip to the exuberant final variation, start the video at 17:05.

If you like the concertante format, have a listen to the Sérénade Mélancolique, the Pezzo Capriccioso and the finale of the second Piano Concerto on youtube or on the spotify playlist at the start of the article.

Tchimes of Freedom

Tchaikovsky wrote seven symphonies altogether, and while they aren’t as immediately accessible as some of his other orchestral works, they are nevertheless some of his most serious and significant achievements. The first three symphonies are hugely underrated, as is the unwieldy Manfred symphony, extracts of which can be found on the spotify playlist at the start. For our purposes, however, I’m going to focus primarily on two of his mature symphonies - the Fourth and the Sixth.

Tchaikovsky wrote a detailed explanation of what he wanted to get across in his Fourth Symphony, including an exploration of the nature of fate, which is signalled by an ominous motif in the brass section at the very start of the piece, and recurs frequently throughout the rest of the symphony. As a taster, here’s the final movement, which is punctuated by a series of violent outbursts. For me, it’s the musical equivalent of being hit over the head with a frying pan. Watch out especially for the fate motif at 4:50.

The Fifth Symphony is a complex piece which can take some getting used to, as it is unified by a recurring motif in a way which had previously been used in opera. It is one of Tchaikovsky’s most important works, and you can listen to it on the playlist at the start of the article.

For now though, we’ll skip ahead to the Sixth Symphony, also known as the “Pathétique” symphony, which, like the Beethoven piano sonata of the same name, is intended to evoke strong emotions. This symphony is perhaps Tchaikovsky’s most profound and beautiful work, at times bleak and even painful to listen to. The composer died shortly after conducting the symphony’s premiere, leading some to describe the work as a Requiem, or even a musical suicide note. For me, the first and last movements feel like the sound of someone trying to deal with overwhelming and difficult feelings, perhaps unrequited love. But this is by no means a depressing piece of music - the two middle movements are strangely light and airy, making any attempt at a single, simple interpretation difficult to sustain. This is music which is full of contradictions and defies verbal explanation.

The symphony really needs to be appreciated as a whole, so I’ve included a complete performance below from the legendary Herbert von Karajan and the Vienna Philharmonic. The first movement is structurally complex - it starts slowly and quietly with a bassoon emerging from the eerie fog created by the strings. At 2:35, things start speeding up a little, gradually becoming more and more dramatic. Then at 5:25, a stunningly beautiful new theme arrives, building in intensity at 8:05, but just when you think things are starting to calm down, Tchaikovsky starts dropping orchestral bombs – first at 10:25, then at 12:45, before a massive, horrifying brass fanfare at 13:25. Finally the beauty comes back at 15:00, this time with a kind of desperate intensity, like the return of a painful memory. Eventually the whole movement winds down at 17:45 into a satisfying finale. The second movement (19:15 onwards) is dance-like and relatively simple, and the third movement (28:25 onwards) is full of punchy tunes. Then comes the final death blow of the fourth movement at 36:55. It overflows with tormented melodies before eventually fading away into the gloom. Listening to it carefully is like watching someone weep uncontrollably and not being able to do anything about it. Enjoy!

Aside from the symphonies, there are also a handful of other orchestral oddities worth hearing. Firstly the stirring Serenade for Strings, and secondly the deeply underrated and highly individual orchestral suites, which Tchaikovsky used as a kind of musical laboratory for testing out new ideas. The zany second suite is one of the very few classical pieces I can think of which uses four accordions playing at once, while the fourth is entitled “Mozartiana”, and was composed to celebrate the hundredth anniversary of Tchaikovsky’s childhood favourite – Don Giovanni. The last movement is a particular favourite of mine – Mozart wrote a set of piano variations on a tune from an opera by Gluck about a pilgrimage to Mecca, which Tchaikovsky then rearranged for orchestra. It’s an obscure piece with a convoluted history, but it’s a lot of fun and shows of Tchaikovsky’s genius for orchestration.

Ballets Russes

Even after all those masterpieces, we still haven’t exhausted Tchaikovsky’s endless wealth of orchestral invention. In fact, the best is yet to come, because Tchaikovsky’s three ballets, The Nutcracker, Sleeping Beauty, and, most famous of all, Swan Lake, are the most enjoyable works of all. All are based on fairy tales, and in total they amount to more than six hours of music, pretty much all of which is of an incredibly high standard. Ballet seemed to be the place where Tchaikovsky felt most at home, and the genre suited him incredibly well. Tchaikovsky placed more importance on the standard of the music than the demands of the dancers, which initially meant ballet companies deemed his work “undanceable”, but today his works form the core of the ballet repertoire. Tchaikovsky elevated the entire genre as a new area for serious composition, taking the French ballet composer Délibes as his model. Tchaikovsky even regarded Délibes' works, such as Coppélia and Sylvia, as superior to his own efforts. Tchaikovsky also managed to sneak new innovations into seemingly fluffy music – the Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy made use of the newly invented celesta.

As with the tone poems, it isn’t vital to know the story of each ballet, as the music functions perfectly well on its own, and you also don’t need to listen to each ballet in full, as Tchaikovsky helpfully produced miniature versions of each one. The three suites contain highlights from each ballet, and are a great introduction if you’ve never encountered them before. I’ve included all three suites in the spotify playlist at the start of the article, but if you want to listen to the full ballets, then I really recommend the recordings made by André Previn. These are a few of my favourite extracts to get you started, some of which are so well-known that they even made it into the occasional post-punk classic.

The Finale of Swan Lake:

The Panorama from Sleeping Beauty:

The Waltz of the Flowers from The Nutcracker:

And of course, if you want to get the full effect of music and ballet together, you can find full versions of each work here, here and here.

Sweet Tchild O’ Mine

Tchaikovsky didn’t write a huge amount of chamber music (he hated the sound of string instruments combined with a piano), but when he did, he got it absolutely right. When his friend and mentor Nikolai Rubinstein died in 1881, Tchaikovsky was devastated, but out of grief came one of his most breathtakingly brilliant pieces – the Piano Trio. Personally, I think this is one of the most insanely underrated pieces in all chamber music. Produced at the end of a long period of creative drought for the composer, it is absolutely packed with melodic invention and powerful themes, as if everything he had been bottling up for years before had suddenly found a release. Here’s the astonishing final movement:

Perhaps the most famous of all Tchaikovsky’s chamber pieces is the first string quartet. For the slow movement, the composer used a tune he heard being whistled by a carpenter at his country home, a tune which closely resembles the famous Song of the Volga Boatmen. Tchaikovsky took this stirring anthem and transformed into a piece of lyrical beauty. Here’s the Borodin Quartet (named after one of the composers who made up “The Five”) performing it:

And if you like those pieces, try listening to Tchaikovsky’s richly textured string sextet, Souvenir de Florence, or the similarly-named but completely different Souvenir d’un lieu cher. Tchaikovsky also wrote quite a lot of solo piano music, but one work stands out – The Seasons, a cycle of twelve pieces, one evoking each month of the year. The June Barcarolle is one of the best known extracts, along with the November Troika, which was one of Rachmaninoff’s favourite encores, but to get a sense of the whole set, watch this charming Russian animation instead:

A Night at the Opera

Opera is often regarded an entirely Italian/German affair, but the Russian operatic repertoire is also filled with hidden gems. While I'll admit that opera isn't everyone's cup of tea (I'll talk about why another time), no introduction to Tchaikovsky would be complete without a mention of his operatic masterpiece, Eugene Onegin. The work is based on a classic novel by Pushkin which was written entirely in verse, and thus well-suited to opera. I won’t give away the plot if you want to listen to the whole thing, but suffice it to say that the story bears some resemblance to Tchaikovsky’s own life. Considering that he wrote literally thousands of letters during his lifetime, it is hardly surprising to hear one of his most beautiful themes during a scene in which a woman writes a passionate letter to the man she loves. Here’s Renée Fleming singing The Letter Scene - the famous part starts at 2:50.

Eugene Onegin also features a couple of great dances, including a Polonaise and a Waltz, but if you want to watch the whole opera, you can find it here. Tchaikovsky’s other main contribution to opera was The Queen of Spades (also based on a Pushkin story) which tells the story of a man who is gradually corrupted by obsessive love and gambling. Here’s Dmitri Hvorostovsky delivering a powerful interpretation of my favourite aria from it. Warning: watching this video may cause you to develop a powerful man-crush:

A full performance of The Queen of Spades can be found here, and if you want to delve even deeper, you can watch the Cossack-laden epic Mazeppa here, both of which are conducted by Valery Gergiev. Tchaikovsky wrote eleven operas in total, and while I can’t pretend to be familiar with all of them, I have included some highlights from a few of the best ones on the spotify playlist at the start of the article.

And that’s everything! If you’re also interested in exploring the music of “The Five”, have a look at this playlist, which contains some of their main works. I also really recommend having a look the brilliant new series of articles by Tom Service which provide introductions to contemporary composers. If you want to ask anything else, or if you’re looking for some classical recommendations, send me a message and I’ll get back to you. Oh, and did I mention that you can also listen to Tchaikovsky's voice?

Read the other columns in The Classical series here.