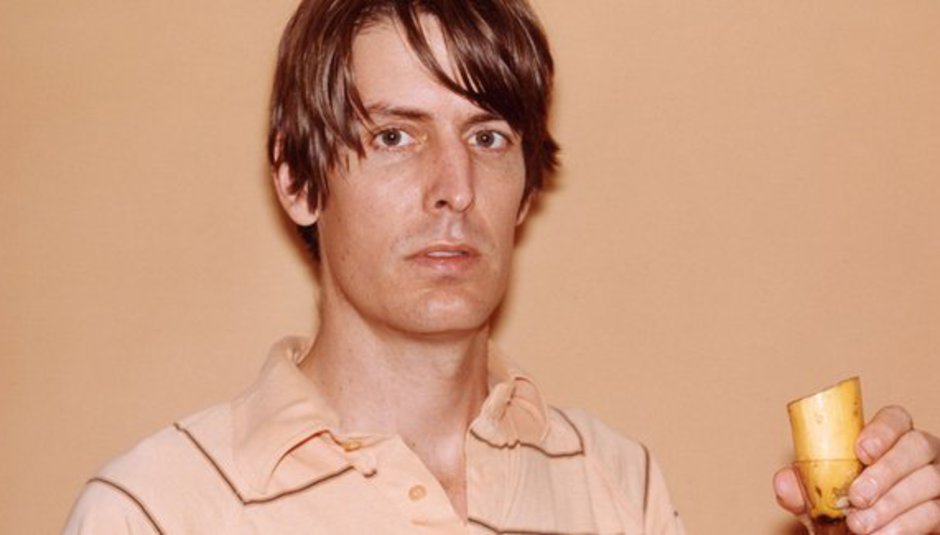

“I don’t feel like there’s much to be gained by admitting that you’re part of the wallpaper in a capitalist system that you help propagate.” Stephen Malkmus is lying on a sofa in the book-lined lobby of a self-consciously upmarket hotel in Soho. The erstwhile Pavement ringleader is talking about class, about the role of musicians and music fans and about the futility of rebellion, but he’s doing it with characteristic nonchalance. He never quite seems to be taking himself entirely seriously, and as he reclines I realise I’m being offered an irresistible visual metaphor: Stephen Malkmus is so laidback he’s horizontal.

“You can say there is a sort of dilettantism… a sense of saying ‘no’ to this system, just by being a really obsessive music fan, yerkno? Maybe you’re not buying into a lot of what the system and the culture is trying to make you buy into. I say we do that, but that’s still saying it’s ok to be in the system. You’re just on the edge of it; you’re not really outside of it.”

He stretches out on the sofa. He is very tall, or from this angle, very long. His fingers point and weave expressively as he talks and his hands are perpetually in motion, a sort of slow-motion version of hyperactivity. “Not to be, like, a French philosopher or something, but we’ve been co-opted into the bourgeois culture, totally, whatever. We’re like a rough edge. My idea is that the only way that I could be truly avant-garde, or somehow outside the consumption system, is through humour.”

Anybody who is familiar with his song-writing will know that Malkmus possesses a finely tuned sense of the absurd, whether he’s skewering bourgeois culture or the endlessly ridiculous world of rock & roll. Back in 1992, promoting the first Pavement album Slanted and Enchanted, he told Simon Reynolds: “When we play live, we do feel the whole ritual is absurd. Music isn't life and death for us, and it's hard for me to believe that art can be like that.”

Of course, despite, or because of, their apparent indifference, Pavement became the sort of band that are talked about in life and death terms. Robert Christgau called them the “finest rockband of the ‘90s”. Chuck Klosterman noted that for fans they were “the apotheosis of indie aesthetics”. Their reunion tour last year, their only performances together in a decade, seemed to sell out almost before it was announced.

It was a tour which finally laid Pavement to rest - a sort of worldwide victory lap. Malkmus confirms that they are now officially over, although he does hesitate slightly before laying the word ‘forever’ on the tomb of perfect sound. “Well, basically we could do a fat guys reunion tour or something in ten more years again, but it’s done as a creative venture. I don’t wanna rule out some kind of fun, or some major charity. If someone wants to offer us a million dollars to play a charity I’m sure everyone would find time to do that.”

With Pavement firmly quarantined in the past, Malkmus is releasing his fifth album with the Jicks, Mirror Traffic, although he points out that his ‘solo’ career isn’t all too different from his song-writing with Pavement. He’s no more or less of an auteur now than he ever was. “In Pavement I had full authoritarian control, for better or worse. It’s no different, really. I write the tunes, the band plays them, and if they don’t play ‘em well, we drop ‘em.” His laconic drawl renders tunes as toons. “It’s still the same thing. They almost always say they like them, or they give me the benefit of the doubt to carry through. If they’re not good, we sorta all agree. They don’t have to say ‘That song’s bad’, they just sorta die on the vine.”

For Mirror Traffic, Malkmus had his old friend Beck in the producer’s chair, fresh from his work on Thurston Moore’s Demolished Thoughts. He says Beck was “a pleasure to work with” although this might have something to do with the fact that it doesn’t sound like Malkmus ceded too much creative control: “He’s in the right zone for people like us. There’s no point in trying to, at this age, change someone like me. I think he heard our demos and he realised what we needed was kind of a performance. A good performance and quick, but not overcooked. There’s so many different ways you could work with somebody. I could come there with no songs…”

I mention that I spoke to Charlotte Gainsbourg when IRM was released and she said that Beck, nominally the producer, had written the whole thing. “Yeah, I think he did. He might not have even known he was going to have to do that…” He laughs. “She’s a different breed to the likes of me or Thurston. We got our toons. We play ‘em. He tries to get the right ambience. He’s very Californian. He doesn’t really say many negative things about anything. That’s pretty nice. If he does he sort of couches it in L.A. speak.”

There’s a parallel here, because Malkmus has only worked with a ‘name’ producer once before, when Nigel Godrich was brought in for the fifth, and as it turned out, final, Pavement album, Terror Twilight. “Yeah. I would give production props to this dude Bryce Goggin who worked on early Pavement albums, and I’ve done different levels of mixing and production with different people who didn’t have enough of a name or the power to call themselves ‘producers’. But yeah, this is where someone else had their name on the line, as it were, as a producer, and I took advantage of that in both cases and did a little bit less and just focused on… on um… doing less…” He laughs again, still lazy after all these years. “No! Focusing on lyrics and playing, yerkno?”

How did working with Beck compare with working with Nigel Godrich? “Well, Nigel at that time was much more of a taskmaster… more British… and coming through the ranks of the producer side. More interested in you hitting the right notes. He definitely added more ‘Nigel’, and now that I went back and listened to the record there’s more ‘Nigel’ on there. He was infatuated with delay pedals and, like, echoplex sounds. I let him, like, do it all over that because I was a little worn out on Pavement, I didn’t put up a fight. There should have been less of that on the album and it probably would have been better.”

He is sat upright now, and warming to his subject. It’s obvious that this is a topic he’s given considerable thought to. “But the good things Nigel did were incredible. He’s a brilliant engineer and some things he added I could never… I mean the sound he gets is unbelievable. I don’t know how he does it, but he definitely is a fucking genius at getting sound. Now Beck also gets a good sound too. His engineer works with Nigel - Darryl, the guy that worked with us, so they know some of those tricks. They’re in the same ballpark without the ‘Nigel’ overload. The difference obviously with Beck is that he’s coming more from an artist’s perspective and he’s a little more sympathetic to what I might want to do. He doesn’t care so much about things being in tune. He doesn’t notice, or it doesn’t bug him. He just kinda hears the whole thing as a fan.”

So Beck is less of a perfectionist than Godrich? “Beck’s a perfectionist definitely sonically, but maybe not tune or tempo. Where Nigel just couldn’t help it, back then. He’d be like ‘That’s out of time’. Once you’ve been down that road with Travis or with Natalie Imbruglia, where things have to be right, it’s hard to say ‘I don’t want that’. I bet he’s changed though, now. I bet he doesn’t care as much about that.”

It’s tempting to wonder whether Malkmus himself, now 45 and naming people like Nick Lowe and Bert Jansch as influences for his new record, is feeling mellow? “I can be. I wouldn’t mind being. Not enough to be played in a coffee shop, unfortunately. I would like to be one of those, like, Sufjan Stevens-type people that is soft and the girls love it, but I haven’t mellowed that much.”

There’s a pause, and then he shrugs. “Not that sensitive, I guess. Not a sensitive boy.” I tell him he’s going to have to be a lot more earnest if he wants that coffee shop airplay. “I’m earnest in my unearnestness. I’m not a ‘let’s talk about our feelings’-type person. I talk about feelings but there’s an undercurrent of darkness in the relationships. I just look for that because I like reading stories by John Updike or Richard Yates. I was always attracted to that. There are a lot of unreliable narrators in these songs. It’s not really me, it’s just a person – it’s like some projection of a dark person. Unreliable narrators are more interesting to me. Some of it is just humour, some feeling. Some unreal, some real. There’s no real answer.”

Updike and Yates are two authors with a clear stamp on his unabashedly literate lyrics, but Malkmus is a writer who has always been more concerned with cadence than literal interpretation. In terms of literary influence he offhandedly remarks that Dostoevsky and F. Scott Fitzgerald are equivalent to The Beatles and The Stones but says he’s more likely to read poetry than novels when writing, particularly post-Beat American poets like Jack Spicer and Lew Welch. “Poetry is something I try to keep in my mind. What would they do? But regardless I know I’m not doing poetry so I’m aware that music is really about that year, so I’ll throw in stuff that’s topical.”

Stephen Malkmus, it seems, still doesn’t see music as life and death. He shrugs, “When music comes out it’s like advertising or a magazine to me. It’s not some big work of art, yerkno?”

I look at him and try to decipher his deadpan delivery. Does he really think music is just ephemera? “I definitely do. I know what turns out to be classic could be… I mean, obviously, some things are more ephemeral than others. It’s like movies which are just total pop because they look really bad thirty years later. You don’t wanna ignore your times or the temporality of it. It’s not some ‘uber-text’. There are some talented poets like Charles Olson who are trying to write for all time, for eternity or something. I like him… even when I don’t understand him… but I wouldn’t try to do that in a pop CD that’s like gonna be in Mojo magazine or something.”

The speed with which he dismisses the ‘pop CD’ makes me wonder whether he thinks Pavement were taken too seriously. He rubs his chin and delivers an answer which suggests that perhaps he’s a little more invested in his work than he’d like to let on: “It’s paradoxical,” he says, “Sometimes you wanna be taken more seriously. You wanna be taken seriously and say that you’re not!”

He laughs. “It’s like Bob Dylan. He’s like [affects Dylanesque whine] ‘You don’t understand, man’, but, yerkno, he’s loving it! Deep in his heart he’s loving the attention. You can see it. He wouldn’t be doing it if he wasn’t getting attention. It’s more important to be loved than ignored. It never got to a point with Pavement where it was so annoying as it did for Bob Dylan, where people are looking through his garbage. Then I would probably be bummed out by it.”

There’s always been a sense, though, that Malkmus has wanted to take a step away from the ritual of rock & roll. “Absolutely,” he agrees, although he knows enough rock iconography to point out my skull ring. “I like your Keith Richards ring,” he says. “He’s one of my favourite guitar players actually. People might not expect that, but he is.”

If making music is just magazines and advertising, what keeps him going? I ask him what his favourite part of the job is: “Probably somewhere in making an album when you’re first listening and you realise you’ve done something that you and your twenty friends think is special, at least. That’s all you can rely on!” he laughs. “It’s in that record producing thing because that’s more final. Shows are really fun, but they’re so temporal. You do it and it was amazing but then it’s gone and there’s no… it could be a sort of a payoff but also you can work so hard on that show and it could be so amazing, more amazing than the album, but you just… no one will ever know, so it’s like this wasted energy. So it’s kinda sad. That’s frustrating and good and just so temporal. So it’s more in that recording time. Also, it’s fun getting positive feedback from people, like: ‘Hey man, I like what you did. We’re friends by proxy because I like your shit and you’d probably like my shit. That’s the most rewarding.” He pauses, then deadpans: “And then the big fat cheque from the music placement in the Guinness ad, that is, like, totally what I’m there for.”

He smiles. “That’s never happened, so I don’t know.” Oh well, I tell him, everybody has to have a dream. Maybe if you knuckle down and fly right you’ll end up in Guinness adverts and get played in coffee shops. “Well, that’s right,” he says. “If I really wanted it I’d probably already have it. I tend to believe that, within reason. That you can get what you really want.”

I get the impression that Malkmus has an uneasy relationship with his success, so it seems worth asking whether he really did ‘want it’? “Not really… on my own terms,” he replies, with just a trace of melancholy. “If I could have done as much work as I did and be Arcade Fire I think I would like it. It’s gotta be fun to be just travelling at that level. Being the headliner, blowing people away and stuff. That must be fun, and I never really did that.”

I think I visibly cringe when he says this. Oh come on, man! Don’t tell me you, Stephen Malkmus, want to be Arcade Fire! For a start, surely the Pavement reunion tour was pretty damn huge? “It was, but it didn’t feel… the moments were of the past, a bit. Maybe sometimes when Pavement was going it felt a little like that, but unfortunately on the rock & roll treadmill once you start doing festivals you’re constantly reminded where your status is…”

I laugh at this, and it turns out that Malkmus has a thing about that classic rock hang-up, the festival hierarchy ego battle: “I was looking at this advert in a magazine for this festival, it looked like a cool festival. It’s one where Björk’s headlining.” Bestival? “Yeah. We’re not playing it this year, but we might next year. I started scanning and I was like ‘we’re gonna be right THERE’,” he jabs the air with his index finger. ‘There’s Graham Coxon, we’re gonna be right… probably two above where his name is, or something, judging by the names… regardless of how good or well-received our album is. That’s where we’re gonna be.’ It’s like, that’s where you stand. It’s pretty funny. Those festival charts are the most incredible class systems. I was thinking about it because there’s this one festival in there that has like James Blunt headlining…” I think he means Guilfest? “Yeah, it’s like… not an elite festival. It’s obviously low money, for the bands. Probably cheap for the punters too, which is good, but it’s definitely like ‘well this festival is in this class, and this one is this way’. There’s enough of them that it’s not like you have just three classes. There are millions of ‘em.”

Stephen Malkmus shakes his head and shrugs in mock amazement. He’s back here on tour in November, and then look out for him on the festival circuit. Spare a thought for where he lands up. He’ll be there somewhere. Right there. Probably two names above Graham Coxon. Not yet a senile genius. No need to reinvent the wheel. Not mellow enough for coffee shops. The rough edge of bourgeois culture. Still finding the whole thing faintly absurd. Still slanted. Still enchanted.

Mirror Traffic is out this week on Domino.