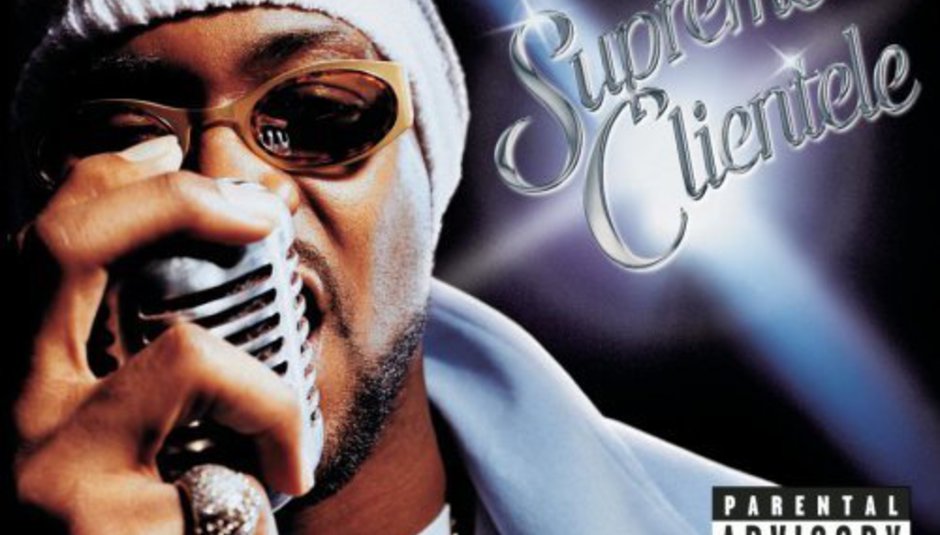

As part of our 10-week "DiS is 10!" celebration, we have asked 50 of our favourite people to tell us about one of their favourite albums of the past 10 years. In our fourth "favourite 50" installment, DiS contributor Nick Neyland, shares his choice...

Supreme Clientele was all about bucking trends. It came hot on the heels of some distinctly limp wristed Wu-Tang solo efforts, as anyone who can remember Method Man’s Tical 2000: Judgment Day, GZA’s Beneath the Surface, Raekwon’s Immobilarity, or U God’s Golden Arms Redemption will recall. But while the RZA’s alchemical input on those releases was minimal, perhaps offering a reason for his most famous charges seeming out of sorts, he also only surfaced sporadically on this second sole effort from Dennis Coles (aka Ghostface Killah, aka Tony Starks, aka Iron Man). On paper, the recruitment of Juju from the Beatnuts, former Tupac acolyte Choo the Specializt, and Wu-Tang backroom engineer Carlos Bess (among others) in the production chair(s) didn’t exactly bode well in light of the RZA-shy solo Wu efforts that had come before.

It may have felt like Coles was up against it, with a stint in Rikers just behind him, the daunting prospect of following up the superlative Ironman on his hands, and only a bunch of RZA acolytes at his disposal. It’s conventional wisdom that many hip-hop albums have suffered from having too many hands on the tiller. But not this one. It’s fast, fierce and funny, often within a couple of beats, with Coles’ rhymes coming at a furious clip as he demonstrates a vocal elasticity that few rap artists could ever hope to equal. It’s also a surprisingly coherent work, suggesting that RZA’s executive producer role was more than just an obligatory liner note credit, with the familiar flavour of old soul samples proliferating throughout, but twisted through the Wu grinder—just check out how menacing and cinematic producer Carlos Broady made the string part from Lamont Dozier’s ‘Shine’ sound on ‘Saturday Night’.

The most appropriate sample here is on ‘Apollo Kids’, which extracts the wild horn blast from Solomon Burke’s soundtrack to the 1972 blaxploitation flick Cool Breeze, which was a nutzoid version of John Huston’s classic noir, The Asphalt Jungle. Huston’s film famously followed a legendary crime boss who was just out of jail and had decided to recruit a mob of shady characters to pull off an audacious job he’d ingeniously mapped out. The parallel in circumstances can’t have been lost on Coles, fresh out of jail himself, spilling rhymes about cocaine and crime, corralling a mixture of experienced hands (in the case of this track, his common sparring partner Raekwon) and young aspiring producers, with the Wu-Tang facing critical maulings and having to pull something mercurial out of the bag in the shape of Supreme Clientele.

‘Apollo Kids’ is followed by one the greatest cuts in RZA’s canon, the claustrophobic, utterly condensed groove of ‘The Grain’, which was inexplicably nixed from certain versions of the album, but contains a supremely creepy two-note piano lift from Rufus Thomas’s otherwise joyous ‘Do the Funky Penguin’. It edges closer to the Ghostface- the-lothario persona Coles would later adapt with mixed results on the Ghostdini record, and is further explored on the wistful ode to his teen skirt chasing days on ‘Child’s Play’. ”Those were the days right there”, Coles recalls in the spoken outro to the song, “You'd just come in school for half days, and all that/Just to see that little girl right there”. But he couldn’t (yet) fully commit himself to that path at this point, quickly correcting himself with recollections about going home and humping the bed. And who said teen romance was dead?

At times it feels like Coles can turn his schizoid cut-up rhymes to almost any topic, such is the breezy confidence with which he approaches this recording. From typical rap braggadocio (“When we hug these mics we get busy…Don't fuck with Ghost, you'll feel sorry” from ‘Mighty Healthy’) to sketchy character work (”Nice like Van Halen, seen him at the tunnel with his skin peelin’/Did two days, thought he was jailin’” from ‘Malcolm’) to darker material set to beats so propulsive that the disparity between subject matter and instrumentation is disquietingly stark (See: “If we want a nigga dead, we pay the cash,” rapped over the uplifting sliding string motif pinched and sped up from Syl Johnson’s ‘I Hate I Walked Away’ on ‘We Made It’).

Ultimately, Supreme Clientele is an evisceration of language, a frenzied grab bag of words spliced together to form narratives that can spin off in multiple directions and don’t necessarily appear to have tangible meaning at first glance. The themes here are mostly typical of the hip-hop milieu (sex, violence, redemption), but what makes it work is the byzantine delivery, which pings back and forth between obliquely convoluted rhyming couplets and unnervingly direct vignettes. This haphazard approach to wordplay positions Supreme Clientele somewhere close to being the hip-hop equivalent of The Naked Lunch, where linearity is tossed out of the window and the battle to extract order from discord, or to simply revel in such a nihilistic approach to language, can equally bring rich rewards.

Credit should also be afforded to the gaggle of producers assembled to bring this project to fruition. The musical chaos that could have resulted from having so many people involved never surfaces—there’s a staggeringly consistent aesthetic at work here, which provides Coles with the perfect axis around which he can wrap his scattershot delivery. It also suggests RZA was wary of all the sub-par material slipping out under the Wu-Tang name, because Supreme Clientele has got his fingerprints all over it, regardless of what the credits denote. But this is Coles’ record, full of his asymmetrical, singular, meticulous perspectives on life, which can simultaneously be grotesque and charming and downright confounding, but are all delivered in a matchless flow that only continues to peel off more and more layers of meaning as the years pass.