In Michael Azerrad’s Our Band Could Be Your Life, the author closes his excellent history of the US underground of the 1980s with a condemnation of the music which came after. He decries the ‘solipsistic’ and ‘limited’ stylistic palette of 90s American indie, and with it the ‘cerebral, ironic’ musicians such as Liz Phair and Palace Brothers who flourished in the post-Slanted and Enchanted landscape, which, in his opinion, was then sadly bereft of politicised, state-traversing titans such as Black Flag and Minutemen. I have always found this rather unfair, and if I were to argue that 1991 was actually where something new and exciting was beginning rather than ending, there is another record from that year which has had arguably a greater influence than any of its well-known big-sellers: Spiderland by Slint.

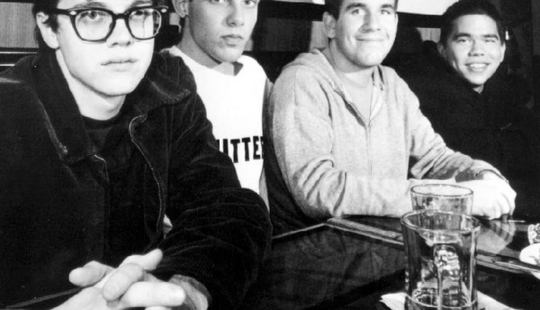

A lot has been said about Spiderland already: how it inspired everyone from Tortoise to Mogwai and Cat Power, how PJ Harvey wrote to the band in response to their request for a female vocalist, how Will Oldham took the photo which became its famous cover, how Steve Albini reviewed it in Melody Maker with the verdict "ten fucking stars", how the band had already ended by the time of its release, how Brian MacMahan went to work in a supermarket and David Pajo went to Norwich University whilst Britt Walford (briefly) joined Kim Deal in The Breeders, how they reconvened to play country music on the first Palace Brothers record, and so on. Much of this came to light even before the three main musicians reformed with a couple of friends and relatives for the successful ATP shows and tours that followed, mainly thanks to David Pajo’s tireless enthusiasm for answering interview questions about the band long after its demise.

What of the music itself? Sebadoh’s Lou Barlow famously said that "it was quiet to loud without sounding like grunge or indie-rock. It sounded more like a new kind of music." Is Spiderland really a "new kind of music"? Even with the benefit of hindsight, it doesn’t feel like hyperbole to say that the album, at the very least, added something to the language of rock music. It’s one of a few records which never fails to sound strange, original and utterly engaging, even after the 100th listen. On the surface, its sparsely intoned vocals, volcanic eruptions of noise and long instrumental passages certainly sounded like the band were operating out there on their own; however, look beneath and there is more. Discordant diminished chords, traditionally passing chords in rock songs (if they ever appear at all), are used frequently to build unbearable tension and ugly walls of fuzz, odd time signatures ('Breadcrumb Trail' is in 7/8, 'Nosferatu Man' is in 5/4) rear their heads for probably the first time since prog ruled the (middle) earth, and the lyrics lay bare a new kind of introspection with vivid imagery (‘his friends stared / with eyes like the heads of nails’ always sticks in my head long after the record has finished) that bears the hallmarks of a kind of dread only previously conveyed in art by the likes of Emily Dickinson.

Had anyone actually done this before? Not really, but there were a few predecessors that dwelt in similar climes. King Crimson’s Red, in which aggressive instrumental noise with cerebral twists and turns is deployed is one starting point, but you’d have to ignore the mellotrons and lyrics about wind that exist elsewhere in their catalogue. Black Sabbath’s 'Black Sabbath' appears to be the starting point for the Breadcrumb Trail chorus riff, but the bluesy noodling which follows has nothing to do with Slint’s post hardcore structures. The final EPs of The Birthday Party, in which the band were mutating from metallic KOers to backwoods murder balladeers, foreshadows the eerie nocturnal sound of Spiderland (check out Jennifer’s Veil for a riff which moves, Slint-style, around a repeated diminished chord and ghostly guitar harmonics). Finally, Pere Ubu’s The Modern Dance deals with a similar notion of dread, and clanging diminished chords underpin lyrics which deal with the malaise of a post-industrial life lived in the shadows.

CODEINE

A life ‘lived in the shadows’ is an apt place to begin with Codeine, arguably the band who – before many of Slint’s more well-known imitators even existed – had already adopted this new musical language and translated it into something even more harrowing and beautiful. There is no record in rock music which more effectively conveys depression and emptiness than The White Birch (1994), so bleak and narcotic is its timbre: "What does the word ‘vacancy’ mean / when you don’t expect anything?" asked the band in 'Vacancy'. Originally from New York, Codeine traded in a brand of slow, doom-laden rock music with occasional spoken word passages. Inspired by Slint, they decamped to Louisville, Kentucky to record their 1994 opus, commenting that "there’s something in the water there". The White Birch is spare and economical, extending the minimalism practised by Slint into new areas. Arriving the same year as debut albums from Low and Bedhead, it played a large part in defining what has since become known as slowcore.

However, The White Birch is not a glacial record soaked in reverb and delay, like the first Low LP [Slowcore ed.: I Could Live in Hope, also re-appraised this week]. The tense and dissonant psychic landscape of Spiderland is extended into slower, desolate open prairie space. The clean diminished chords and dropped D tuning favoured by Slint are utilized to create hanging, reverberating chords on the Telecaster, each of which seems invested with austere emotion. Like Spiderland, the record erupts into harsh noise before dropping sullenly back into an atmosphere of tense inertia. Water imagery dominates the opening songs 'Sea' and 'Loss Leader', in which the "black sea" acts as a metaphor for being engulfed by loneliness; by the time we get to 'Tom' the aura of depression is palpable: "My words have broken throats / Too ashamed to speak / Afflicted by disease / They are so weak". Perhaps the most Slint-like song is 'Wird', a mostly instrumental series of diminished guitar chord movements played through ear-scorching fuzz, occasionally letting up to allow singer/bassist Steve Immerwahr to plead in anguished fashion: "Who built / Who built this machine? / This mechanism? / This misery?"

Is this, as Michael Azerrad argued, the unacceptable face of 90s indie: self-obsessed gloom which ignores "real" social and political reality in favour of ineffectual navel-gazing? Perhaps, but only if we accept that writing about – and representing in musical form – the human interior and its attendant anxieties and emotional states is a form of deviance with respect to "proper" rock music, which comments on the outside world and therefore only makes BIG statements. Whilst it is true that often the most spine-tingling music is that which goes beyond the personal and says something about the world we live in (and there are few more uplifting moments than, for example, hearing Chuck D exclaim "Bass! How low can you go? / Death row – what a brother knows"), it is absurd to suggest that there is not a place for music which dares to explore areas that are virtually taboo in mass media and popular culture: interiority, loneliness and our existential position. If one of the functions of art is to get us to feel empathy – to recognise that other people share our experiences, and consequently to allow us to feel less alone in the reality we face – then this music is essential. 1991 was, therefore, the beginning of a movement which put empathy above cultural comment, and as such represents the influence of the likes of Neil Young and Nick Drake coming to the forefront in indie music (both were touchstones for many 90s bands – just ask Mark Kozelek [of Red House Painters, also reappraised this week - Slowcore Ed.]) . What Slint and Codeine did – and the reason we should value their artistic contributions – is to develop a new strand in rock music’s DNA to accompany the expression of these emotions.

If you’re interested in hearing records made under direct influence from these bands, Cat Power’s What Would the Community Think is a good place to start, as is Rodan’s faster and heavier Rusty (with one track even recorded by Slint frontman Brian MacMahon) and PJ Harvey’s Rid of Me (also recorded by Slint engineer Steve Albini and with one song in particular – 'Missed' – bearing more than a passing resemblance to perhaps Slint’s finest song, 'Washer').

remember me as you fall to sleep / fill your pockets with the dust of our memories / rises from the shoes on my feet / I won't be back here / although we may meet again

I know it's dark outside / don't be afraid / everytime I ever cried for fear / was just a mistake that I made / wash yourself in your tears / and build your church / on the strength of your fears /

please... listen to me / don't let go / don't let this desperate moonlight / leave me on your empty pillow / promise me / the sun will rise again

[quiet chorus riff breaks down into creeping bass solo, taunting the listener with the possibility of exploding]

I'm too tired now / embracing thoughts... of tonight's dreamless sleep / my head is empty / my toes are warm / I am... safe / from harm

[8 minutes in, the song finally erupts into an elephantine riff that surely explains why Mogwai's 'Like Herod' was originally known as 'Slint']

A note on the writer: Richard Riggs was the guitarist in a notoriously abrasive post-punk/slowcore-inspired band who were supported by many acts well known to DiS-readers. As Azerrad would put it, these bands were, for a while, his life.